Intimacy is a slippery word, one increasingly applied with a broad brush. It is a term whose definition shifts shape depending upon who uses it. Is it romantic, platonic, or sexual? Public or private? Is it something between people or places? Does one find it in the past or the present? Is it animal, vegetable, or mineral? A group exhibition entitled Making Light of Every Thing at the Centre de la Photographie in Geneva tries to wrap its arms around the concept, asking whether photography, without reverting to expected tropes, can capture a feeling that is “fleeting and impalpable” in its nature.

The exhibition answers in a novel way; perhaps it is an experimental approach to photography that best tends to this ephemeral theme. The group chosen for the show highlights the idiosyncratic ways artists bend and stretch the medium, and through the variety of formally-playful work on view, encourages the audience to become intimate with images themselves. The assembled artists approach the theme in myriad forms with works utilizing model making, AI-generated imagery, darkroom experimentation, video, and sculpture; manipulated or fabricated imagery, whether made by hand or using digital tools, is the common thread. Whether fully stated or not, all of the work is in conversation with our relationship to reality—through personal, tactile, or digital means—set against the strangeness of contemporary life.

In my first brush with the exhibition, via a press release, I found myself skeptical. Could an exhibition successfully cast such a wide net? Yet the exhibition’s curators, Claus Gunti and Danaé Panchaud, impressively weave this series of transient relationships and broadly diverse practices together, revealing the complex and often strange ways memory and space are constructed. Rather than falling into the expected, the artists they have chosen explore intimacy in distinctly unique ways, reaching across time, creating new spaces, and responding to the digital world that we are all enmeshed in. By combining techniques that span a vast spectrum, from handmade to computer-generated, the curators have also created an incredibly engaging and fresh conversation around image manipulation and old and new technologies.

The exhibition’s layout sets the tone with clever exercises in pairing; forms, colors, and concepts mirror and contrast each other. What at first glance may seem to be too much easily takes shape. The larger-than-life curled paper of a Jessica Backhaus image sits against the curved spine in one of Charlie Engman’s small-scale, early works. The soft, eerie sunsets in Peter Hauser’s high gloss kool-aid bright darkroom prints appear as if reflected in blazing, near radioactive color, against a building complex in an image by the duo Onorato & Krebs.

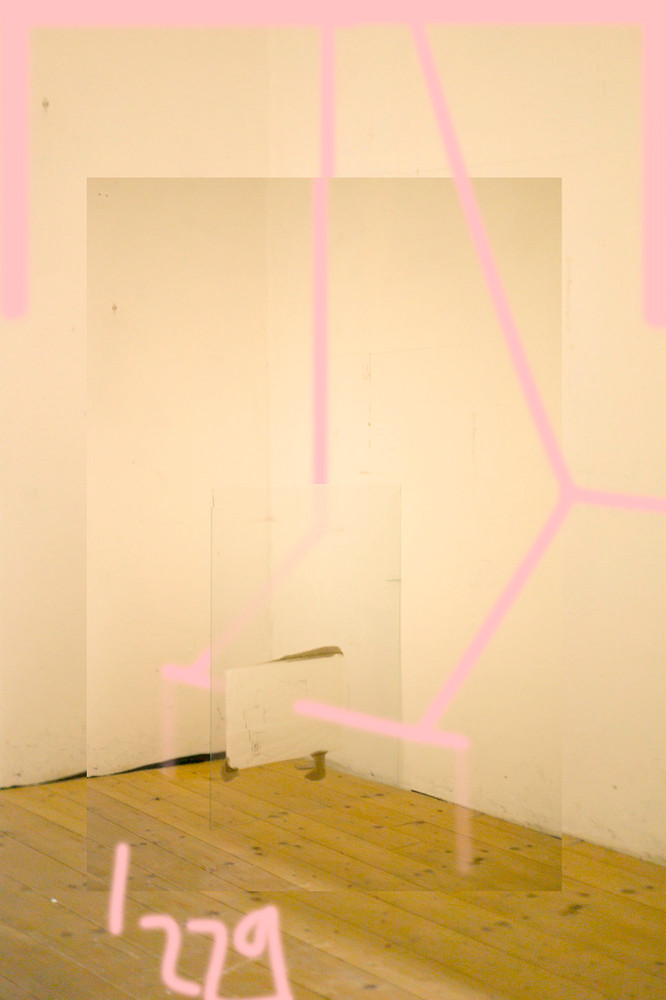

In the same section hangs a work by Martin Widmer, whose two pieces in the show include elements outside of the frame—drill holes, wooden blocks, tape and paint on the wall seem to beckon the viewer to step into the photograph itself, as if it might lead to another room or the photographer might walk in at any moment to finish the piece. Another Onorato & Krebs image on the same wall picks up on this, a glowing city is captured in what might be an open doorway, gaping high above the cityscape, discordant in its juxtaposition of interior and exterior.

The balance of moving between intimacies—from one person’s interior life to another’s environmental observations to another artist’s recollection of home against a dreamworld of generated imagery—keeps the viewer on their toes. Placing works made through various AI technologies amidst ones that take a distinctly analog form builds out a conversation on photography that feels fresh and serious; a welcome approach to AI that goes deeper than simply highlighting technical marvels. Here handcraft and digitally-assisted image making shape the notion of intimacy as something deeply, strangely human and embedded with emotion.

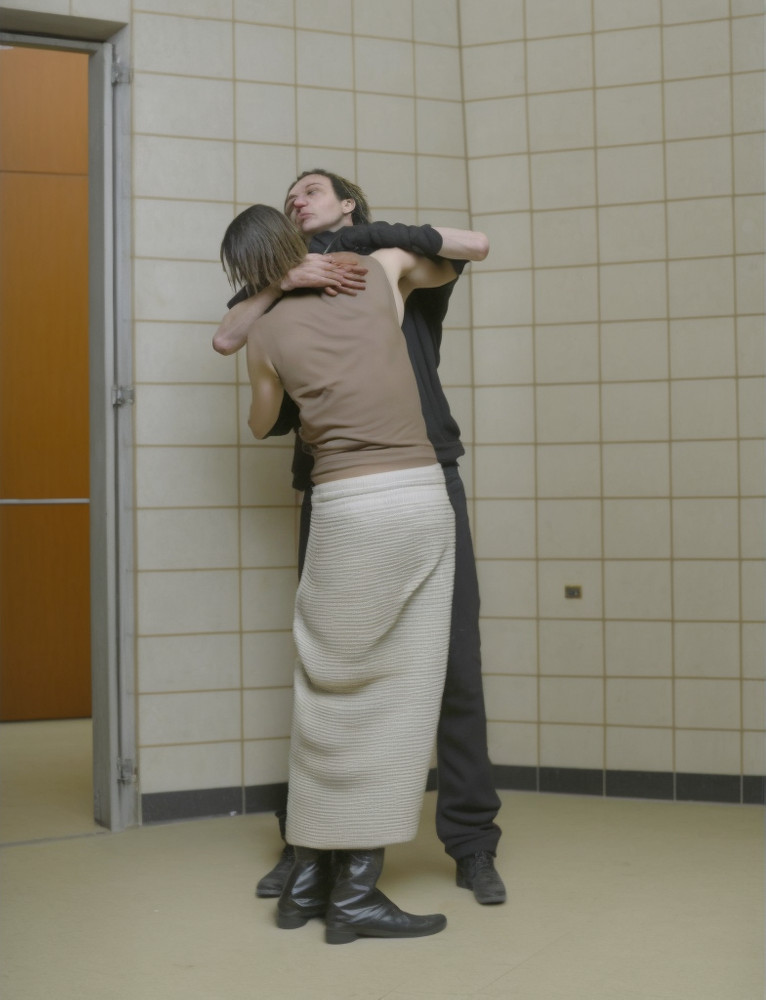

Some projects highlight the limits of these new technologies whilst others cast a light on the ambiguities of human processes such as memory. Charlie Engman, who embraced AI processes into his practice early on, crops up with two projects, created more than a decade apart. In small framed pieces, a body is draped across a series of domestic spaces. The poses emphasize the oddness of the human body, slumped and veering away from classical ideals in art.

Paired here with AI-generated imagery, they feel imbued with new meaning. The AI images, Hallway Embrace and Parking Lot Embrace I, are somewhat crude, oddly surreal, pointing to the weaknesses still inherent to generative imaging technology. We are told of the wonders of AI by the tech-heads of the world, how it will help solve climate crises and discover medical breakthroughs, but at the moment it fails to reproduce that most simple and open of human gestures: empathy.

Mathieu Bernard-Reymond’s strange images from his series I think I’ve forgotten this before, are presented in thin hammered tin and lead alloy frames. The frames, both delicate and rough, encase images of his personal memories. The artist has explained his process of meticulously generating imagery with an astute observation: “Artificial intelligence works a bit like memory.” Composed of archival imagery from the era that corresponds with his memory, they have a dreamlike quality, resembling sketches at times, reading like the beginning of a hallucination when the real world starts fraying into something else.

Perhaps most striking are the works of Akosua Viktoria Adu-Sanyah and Sara De Brito Faustino. Through markedly different creative practices, the physical act of making images becomes a process of working through memories and the act of remembering itself. In a viscerally commanding piece, when you’re in pain, everything is tainted (iteration 02, stitched), Adu-Sanyah reconstructs an image of her father, left blind and disabled after an operation. Encompassing her own photographs, artificial intelligence engines, and color darkroom processing, she manually stitched her father’s portrait together. In another image composed of deep reds and black, flowers, similar to those left on graves, recede into darkness.

De Brito Faustino’s work of recreating rooms in which she has lived, requires the viewer to get close to observe the scenes made by hand. In reconstructing the spaces of painful memories, the artist takes control of the memory itself. The photographs, a blend of cut paper and small objects, blend the intimacy of a childhood experience with the distance of time.

With a hypnotic backing sound, Moritz Jekat contributes a video, The Blue Seals. Extinct and Happy, in which a distinctly impersonal place starts to take on a familiar edge. Set in the public transit simulation game The Bus, an unseen narrator navigates a somewhat sterile environment recounting a relationship, the cold spaces become something more when filled with the narrator’s voice. What at first struck me as distant transformed as I walked through the space. In the bulk of the images on display, we rarely see a face; Jekat’s narrator thus becomes a companion to the show, ultimately leading me back to watch the video again and again.

Elsewhere, the flood of images we live amongst gets put to good use, questioning the intimacy and distance that shapes our relationship to them. Does encountering more images of something bring us closer to it? Leigh Merill’s quietly empty architectural scenes are built from hundreds of images, fusing architectural styles. They could almost be documentary images if it were not for their creeping, uncanny atmosphere. In Alina Frieske’s photomontages, the world of circulated online imagery constructs scenes that feel close to home—portraits or still lives made from downloaded photos that bleed into soft painterly strokes.

Analog works by Peter Hauser are sprinkled throughout the exhibition. Acid-colored shots of clouds, the surface of a pond, and a deep blue fragment of forest ground the viewer somewhere between quiet landscape and science fiction. Hauser’s take on intimacy is both alluringly lush and aware of how the most familiar views can also be the strangest.

If at times the exhibition’s theme seems like a stretch, it may be more a question of size. In the end, it’s in the small details found throughout the exhibition where the theme of intimacy most comes alive—the awkwardness of Engman’s embraces, the slightly oversized basket in one of De Brito Faustino’s sets, the stitches found in Adu-Sanyah’s image of her father, the tone of the voice in Jekat’s video. Perhaps it’s not light that is being made out of every one of these things, but rather meaning in details and observations both near and far.

Editor’s note: Making Light of Every Thing is on view through April 28, 2024 at the Centre de la Photographie Genève.