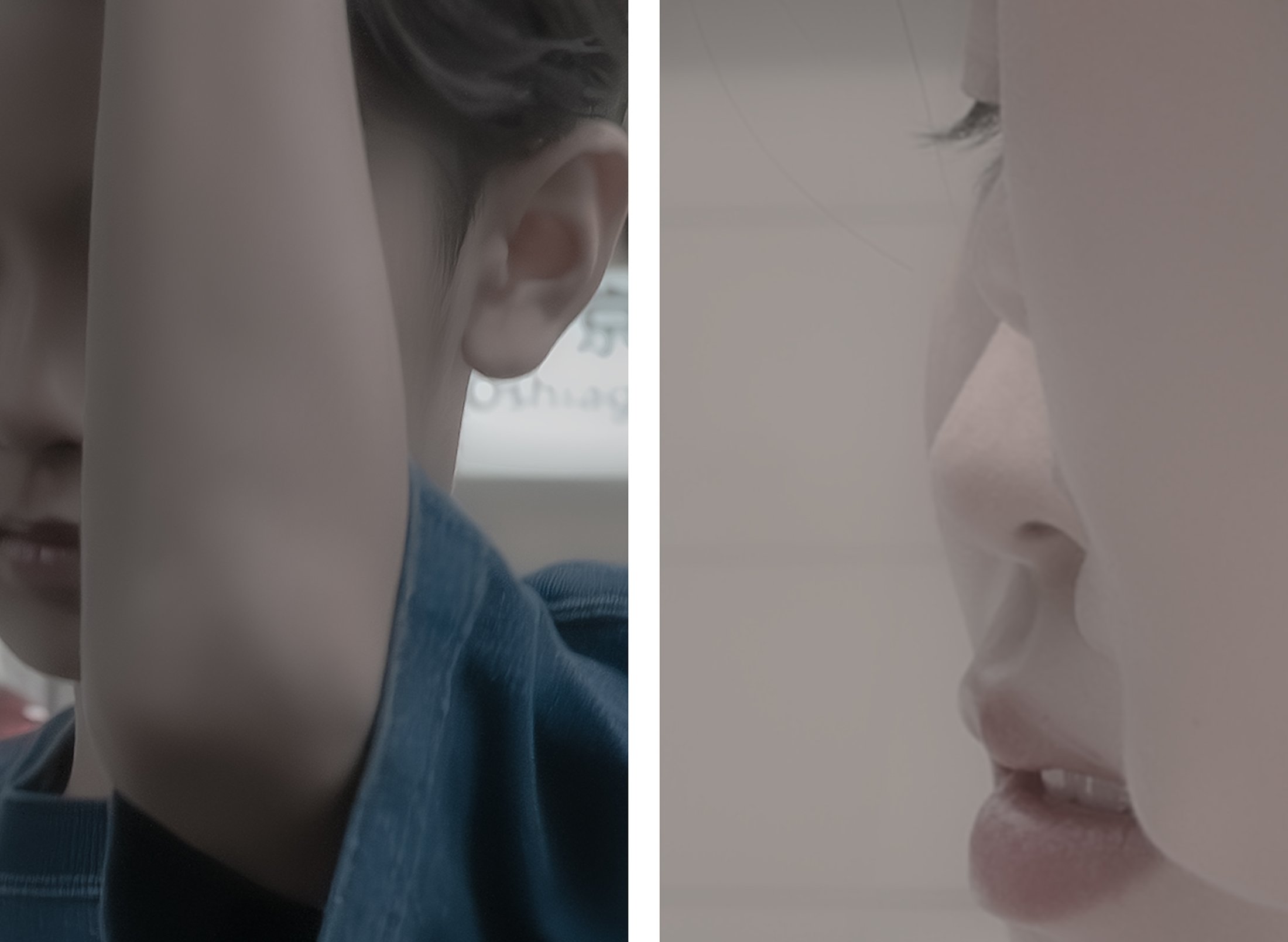

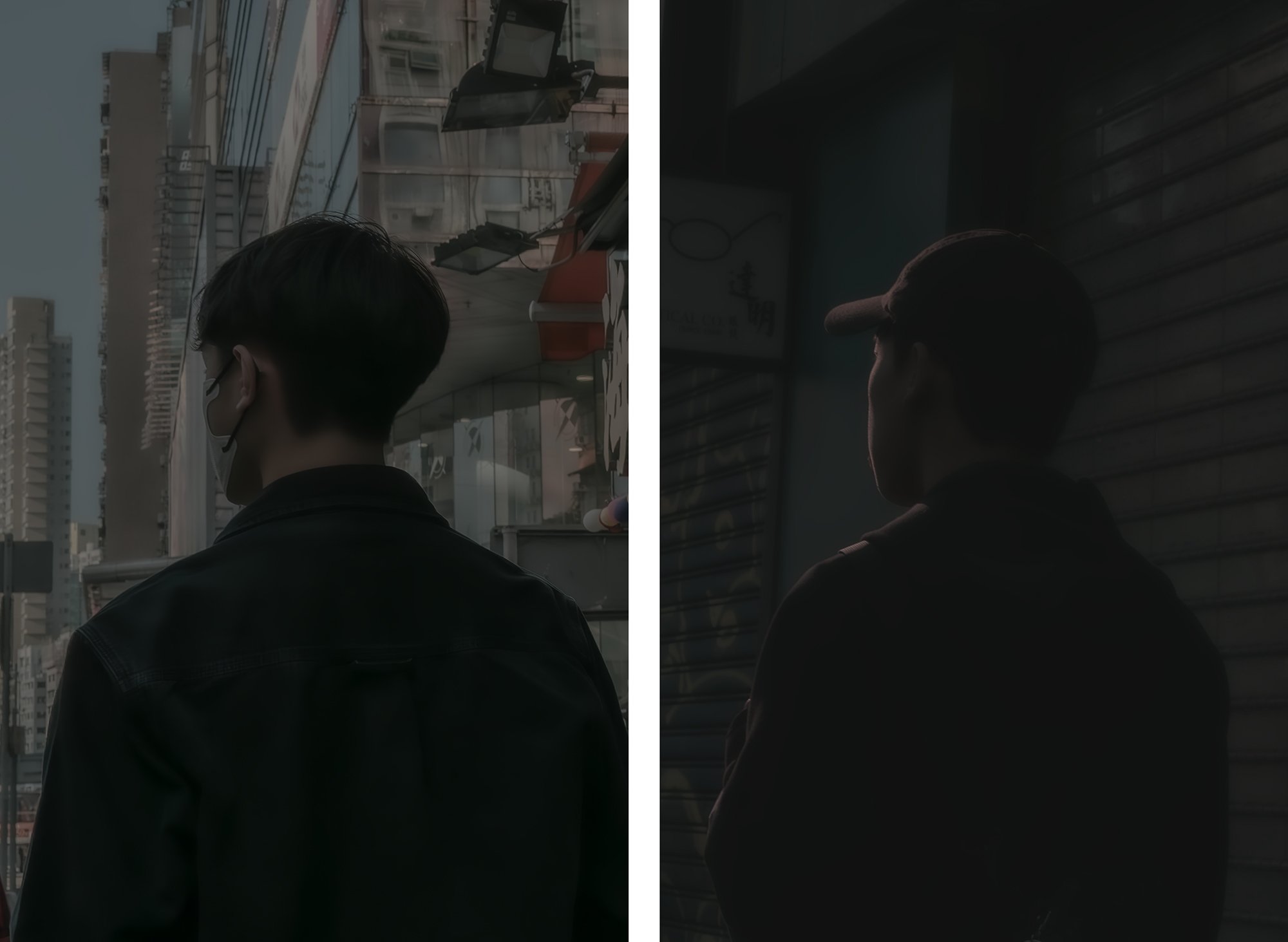

A pair of parted lips. A hand burrowed into a bag. A profile outlined in the barest glimmer of sunlight. The photographs of David Masoko are fragments—of gestures, coincidences, and shifts in posture captured on city streets. In a palette nearly stripped of color, his pieces, rather than purporting to show decisive moments, report from transitional spaces. These are not grand images in the lineage of traditional street photography—no leaps over puddles or triple reflections in store windows here. Rather, they focus on the daily movements we so often overlook. One can say that a life is defined by monumental experiences. We want the new! But in reality, is it not built from the thousands of repeated steps and turns we take—the myriad what-ifs of trafficked streets and busy commutes?

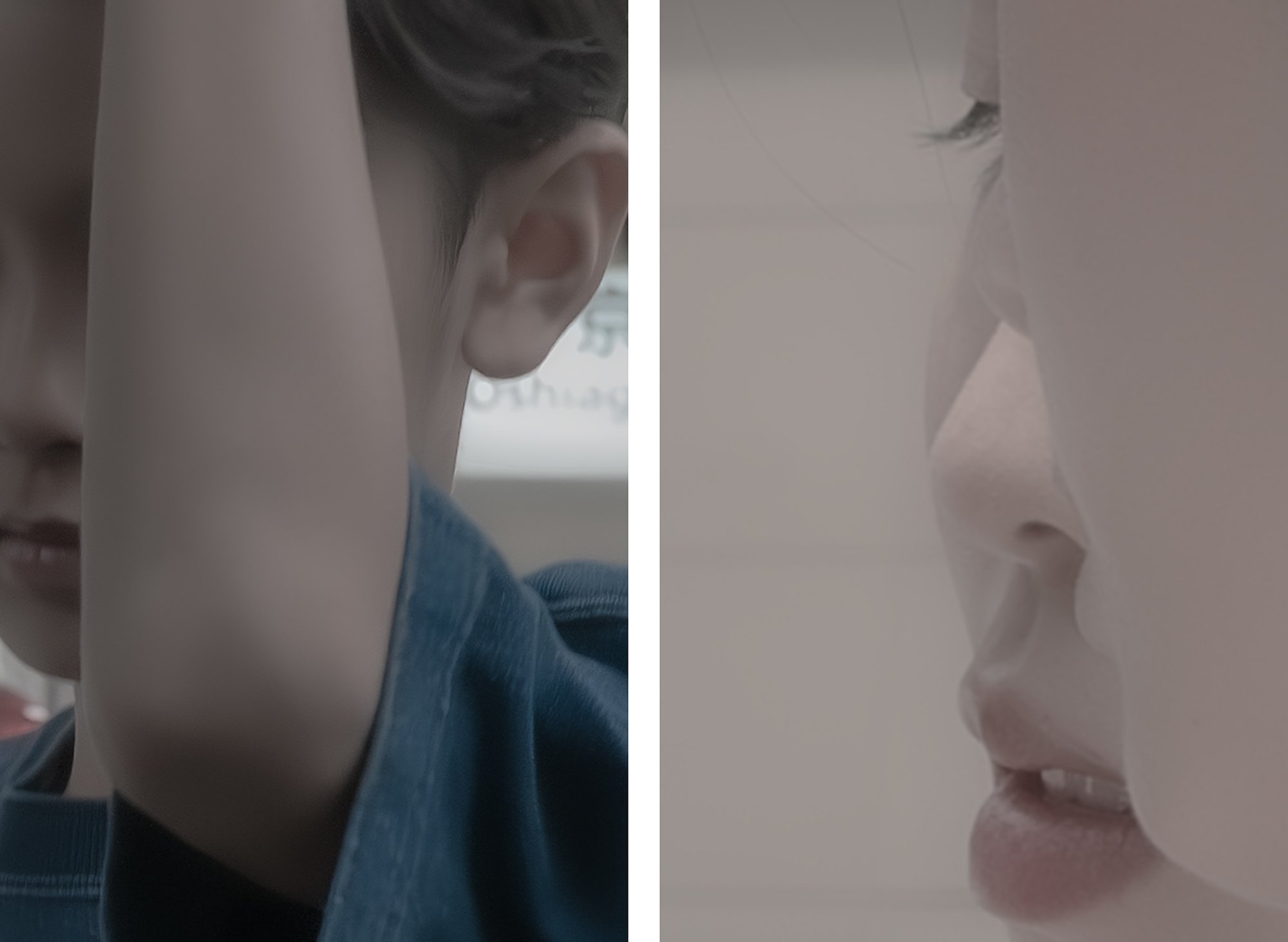

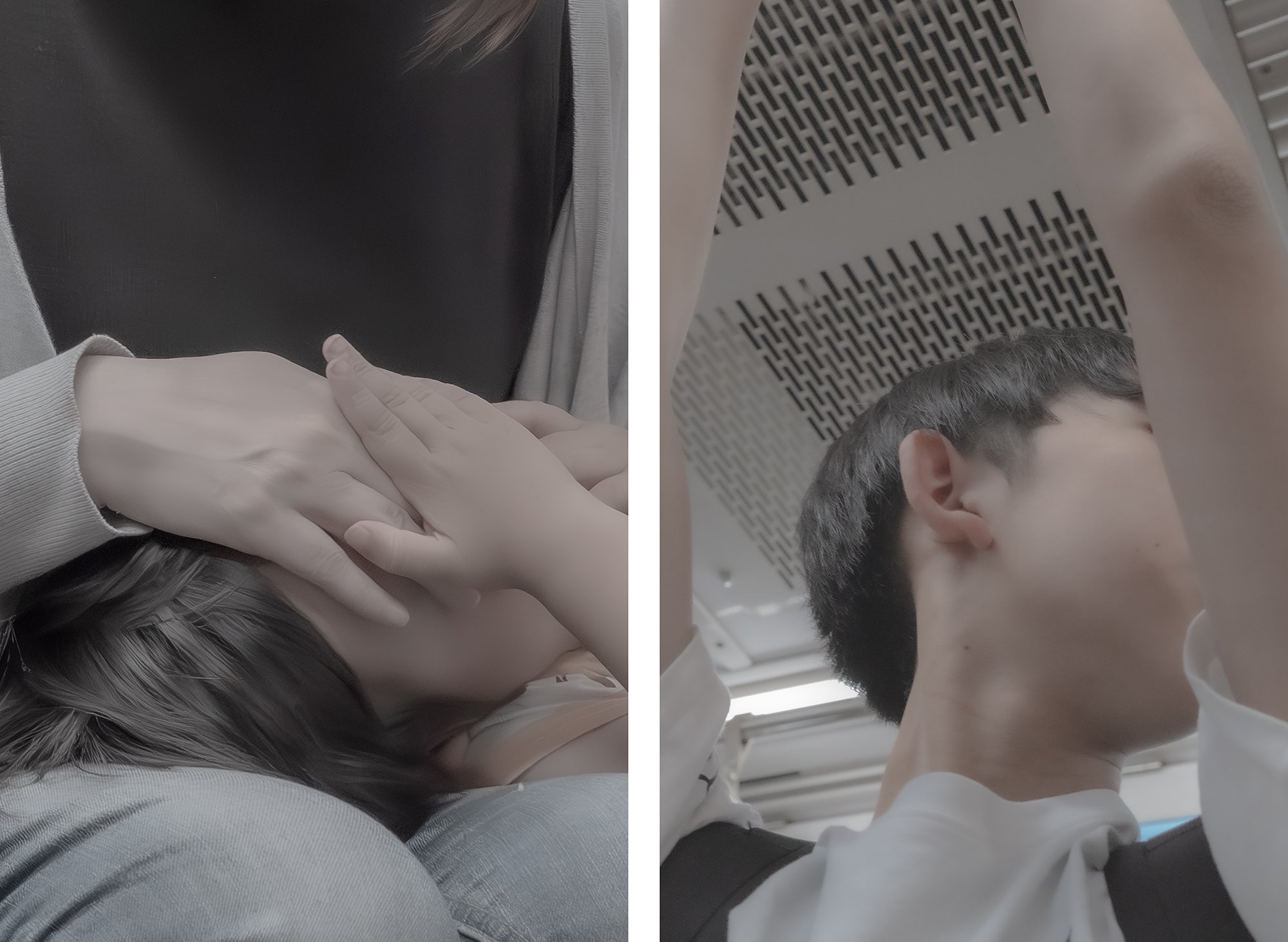

In Dislocated Presences, Masako focuses on a certain distance, the gap between the steps on a sidewalk or the space between a straphanger and a seated passenger on a train. The photographs capture life in bustling cities, from London and Bangkok to Hong Kong and Tokyo. Instead of showing, he suggests, pairing forms that double ambiguously. Is this diptych? A conversation? Or a comparison? Limbs fill the frame, and people are seen from behind, as if just out of reach of the viewer.

“I’m less interested in creating a single punchline and more in fragments—in the way gestures echo, in overlaps between strangers, in the quiet choreography of bodies that may never meet again,” Masoko explains. “Reading Walter Benjamin and later Martin Heidegger made me very aware that every image is a fragment: a surface that hints at something larger, an ‘in-between’ where relationships and meaning unfold.”

This interest in distance percolated during the pandemic. “During the lockdowns, I spent a lot of time at my window looking down at the city,” the photographer explains.“People kept their distance, their faces were covered, and protection and fear shaped the choreography of their movements. When the restrictions were lifted, I went outside with my camera. At first, I made what you might call fairly ‘classic’ street photographs: recognizable moments, clear scenes. Over time, when the masks disappeared, my attention shifted. I became more interested in what was missing from the image: the obscured face, the half-gesture, the sense that something stayed outside the frame.”

One thing outside of the frame is identity. We are unable to distinguish the faces and features of Masoko’s subjects. There is something slightly unsettling and even perhaps radical about his approach. The photographs are close up and on the edge of revealing, yet never crossing, the line. In a world in which the majority of people self-surveil—posting selfies, using tracking apps for personal metrics, uploading diatribes and pitches filmed on their phone cameras—it feels unusual to have identity removed from the equation.

“At first, I simply followed an intuition: I was drawn to people whose faces were partially hidden, to bodies in transition—turning away, passing by, hesitating at the edge of the frame. Only later did I realize how strongly this connected to questions of ethics of street photography. How do you look at strangers with attention without turning them into trophies? How do you acknowledge their presence without exposing their identity?

”The ethical implications of photography, specifically in the genres of street and documentary, are a tale as old as time (or perhaps to be more specific, as old as the 1838 appearance of the first person photographed in Daguerre’s Boulevard du Temple). What does it mean to capture another person’s likeness? To share or profit from an image taken on the street? How has that changed in today’s world, where not only is everyone a photographer, but we are all constantly ‘looking’?

“Working on Dislocated Presences has also made me more sensitive to the power dynamics of looking. Public life is often framed as ‘fair game’: if you’re in the street, you’re available to be photographed and used as an image. I don’t fully accept that. For me, public space is full of vulnerable moments as well as anonymous flows. I try to treat it as a field of overlapping solitudes rather than a theatre where the photographer is the director,” Masoko explains. “Instead of adding more ‘spectacle’ to that world, I try to carve out a small space of slowness, ambiguity and care.”

His editing process is informed by this avoidance of spectacle. Images are paired as diptychs, in which the two halves rhyme or strike notes of dissonance. “I reduce color and soften focus quite deliberately. Slight blur, lowered contrast, and a restricted palette help to quiet down descriptive detail and push the image away from a documentary ‘who is this’ reading,” he explains. “I think of my images almost as short poems made of two lines. The space between the images is as important as what is inside each frame; it’s where the viewer’s interpretation starts to move.”

With Dislocated Presences, Masoko does double duty, prompting the viewer to look both at and beyond his photographs and into a societal mirror. In a world of images, what are we truly looking at?