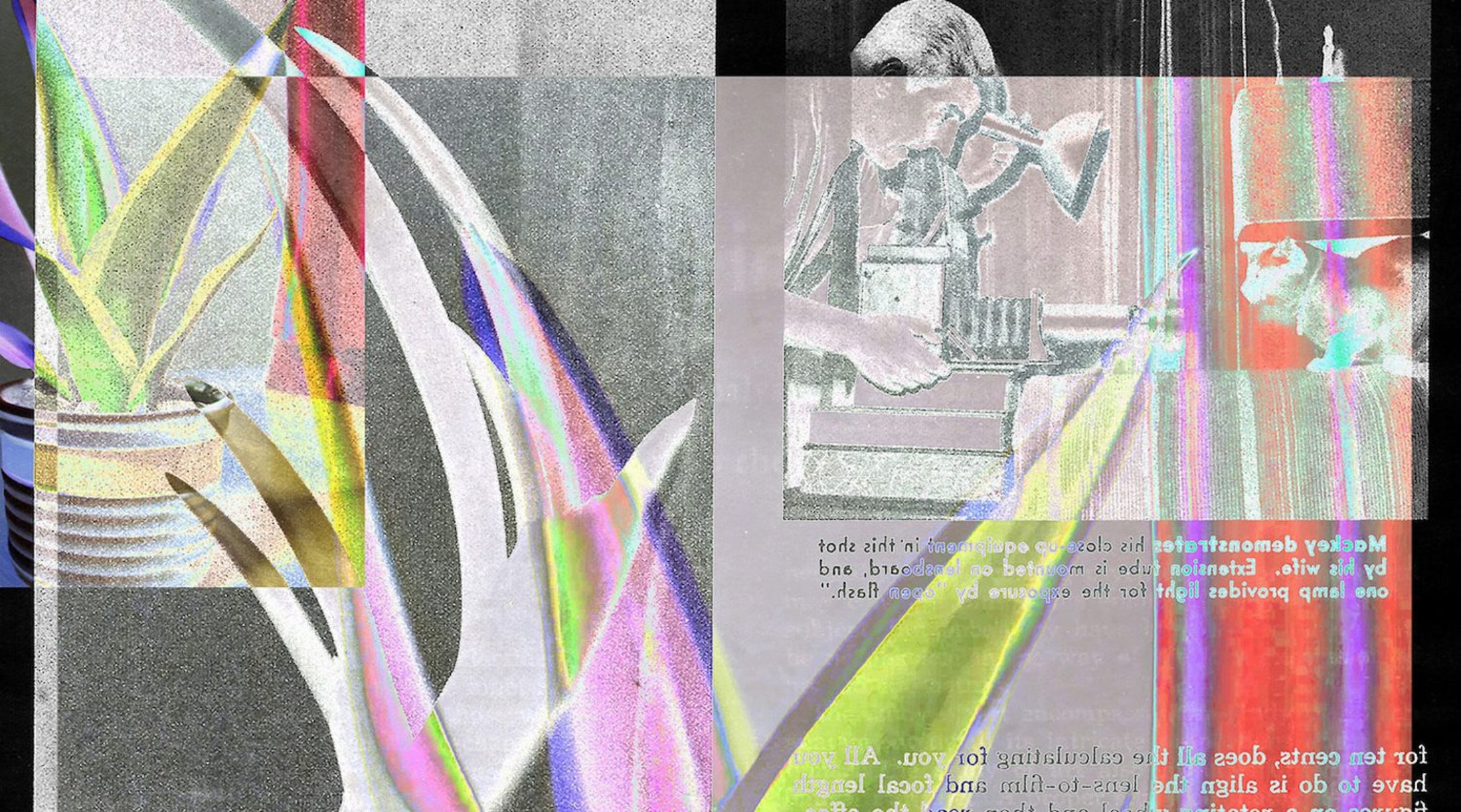

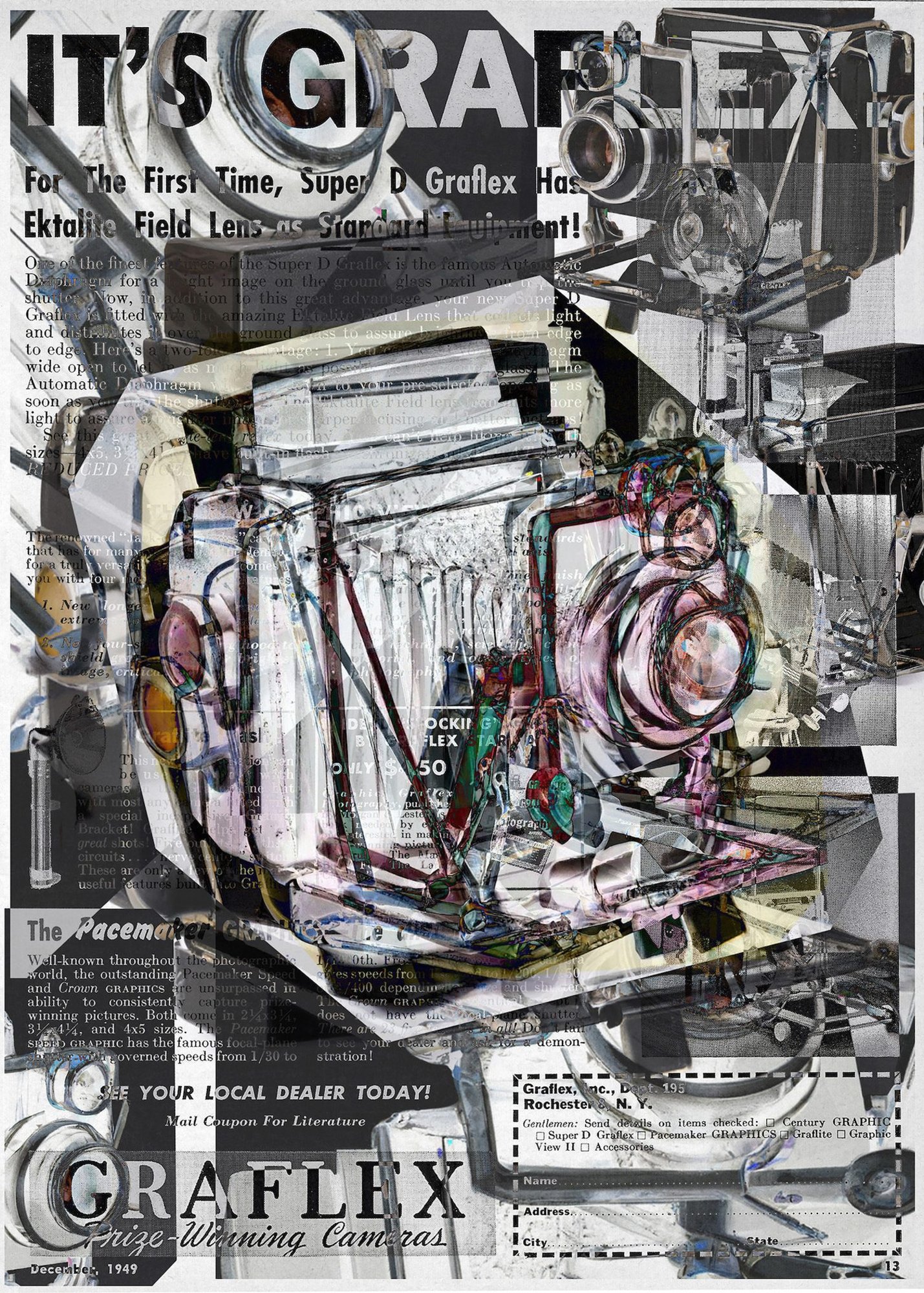

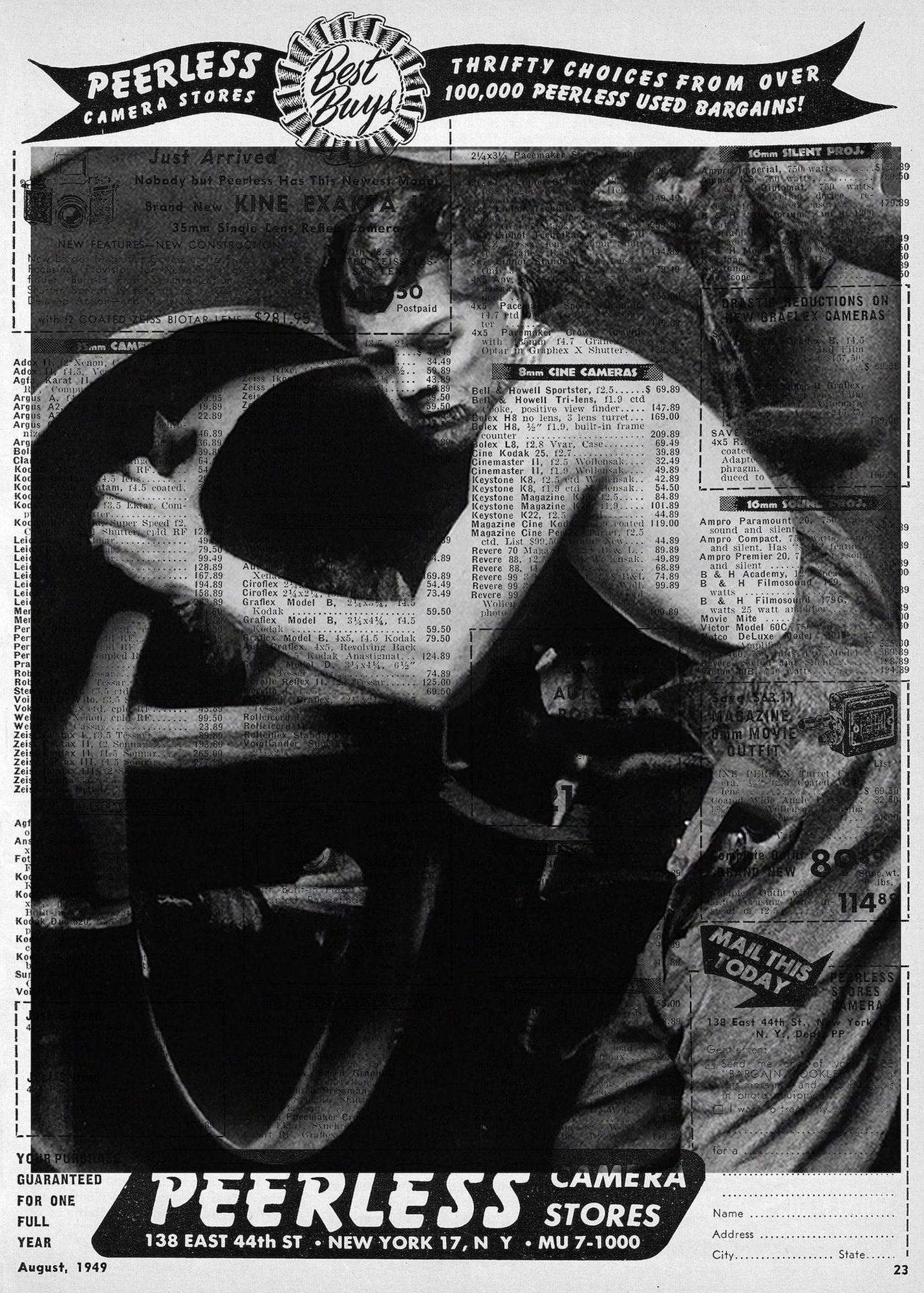

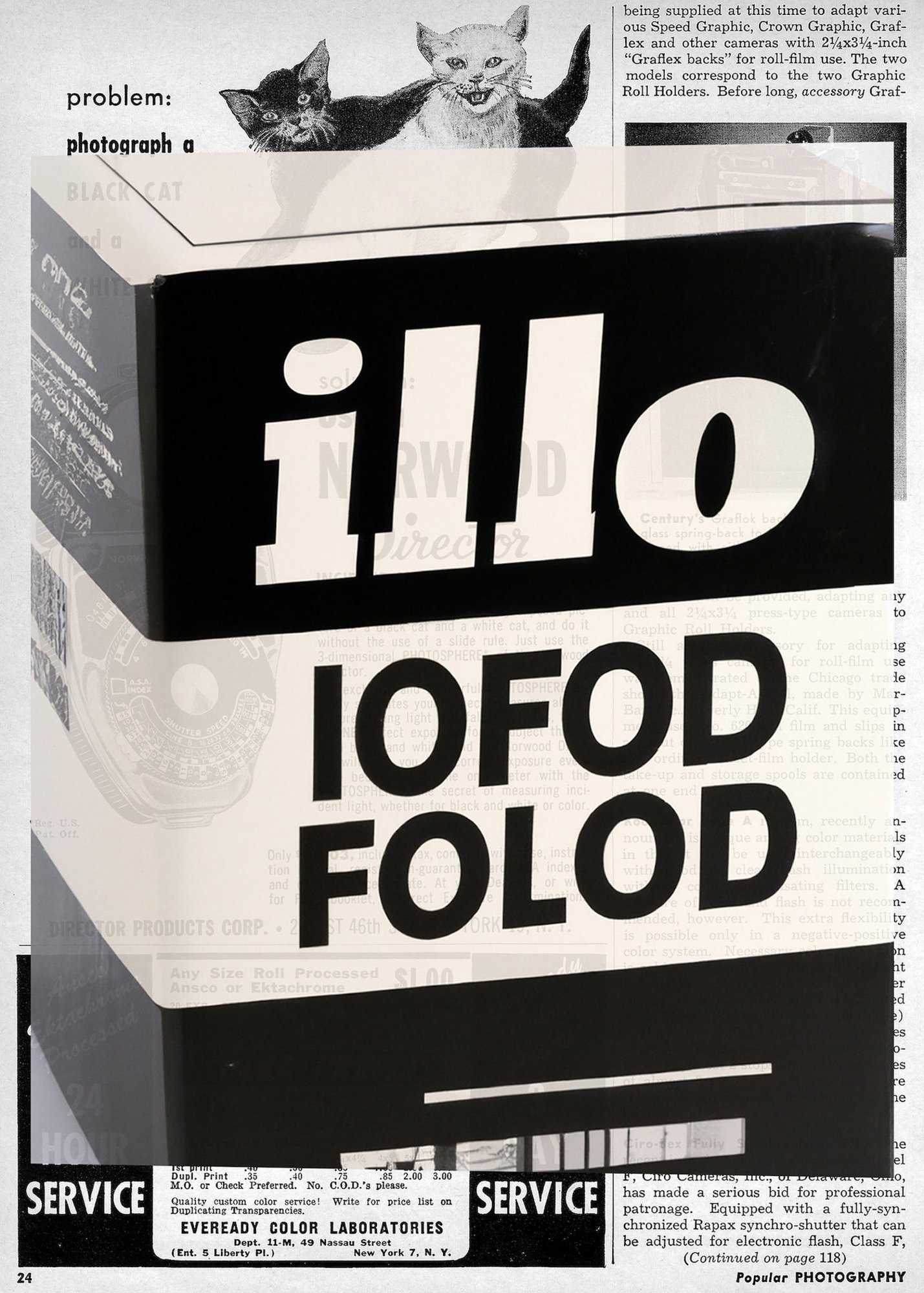

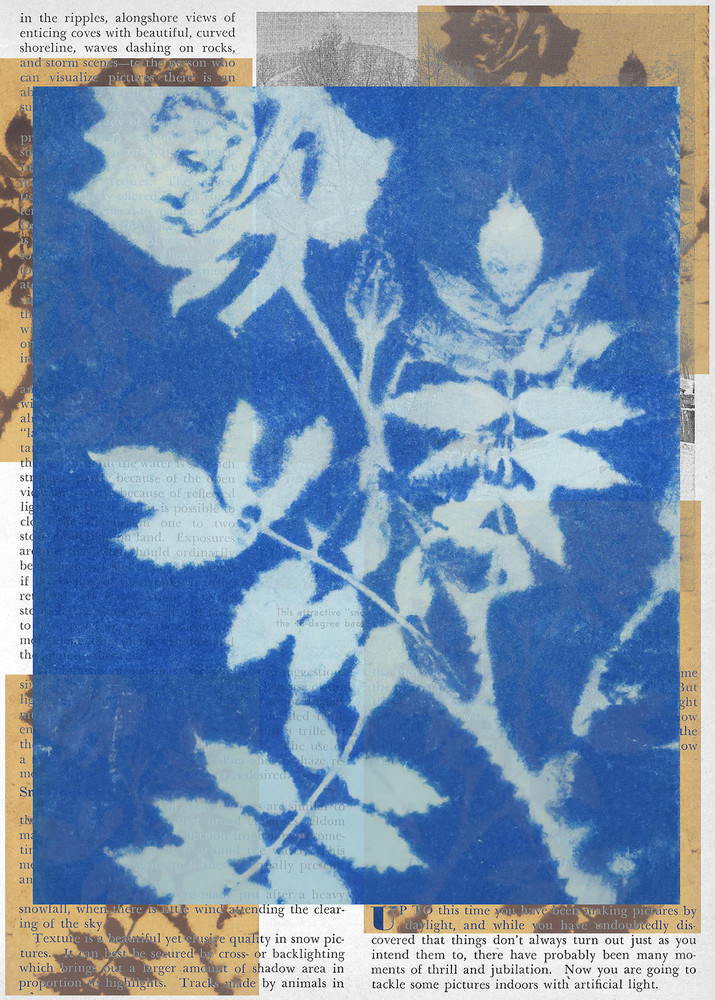

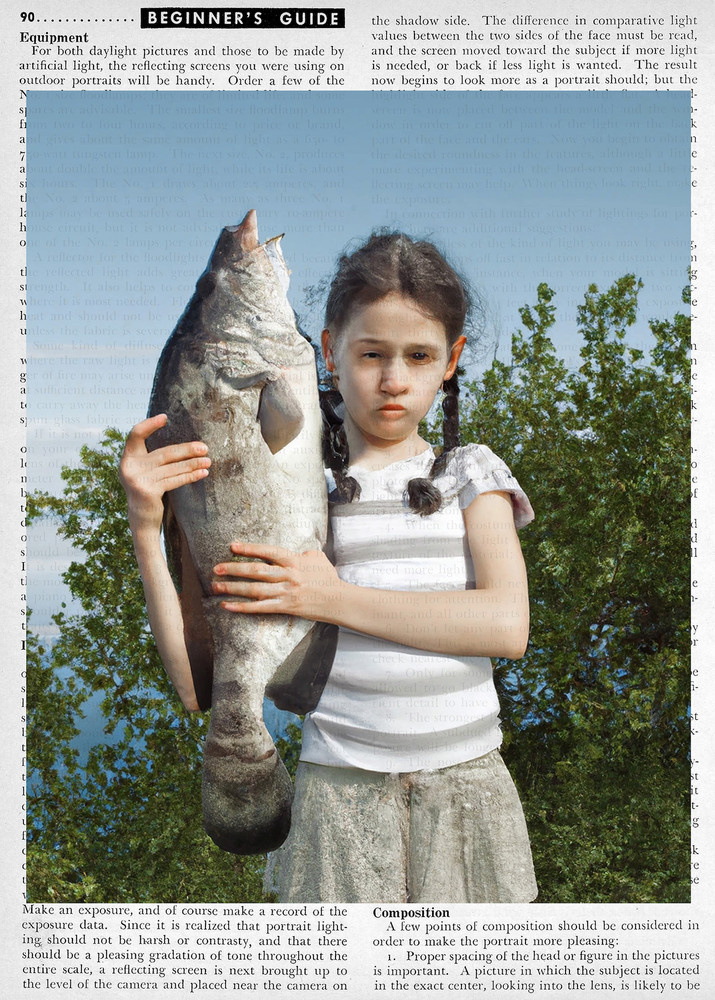

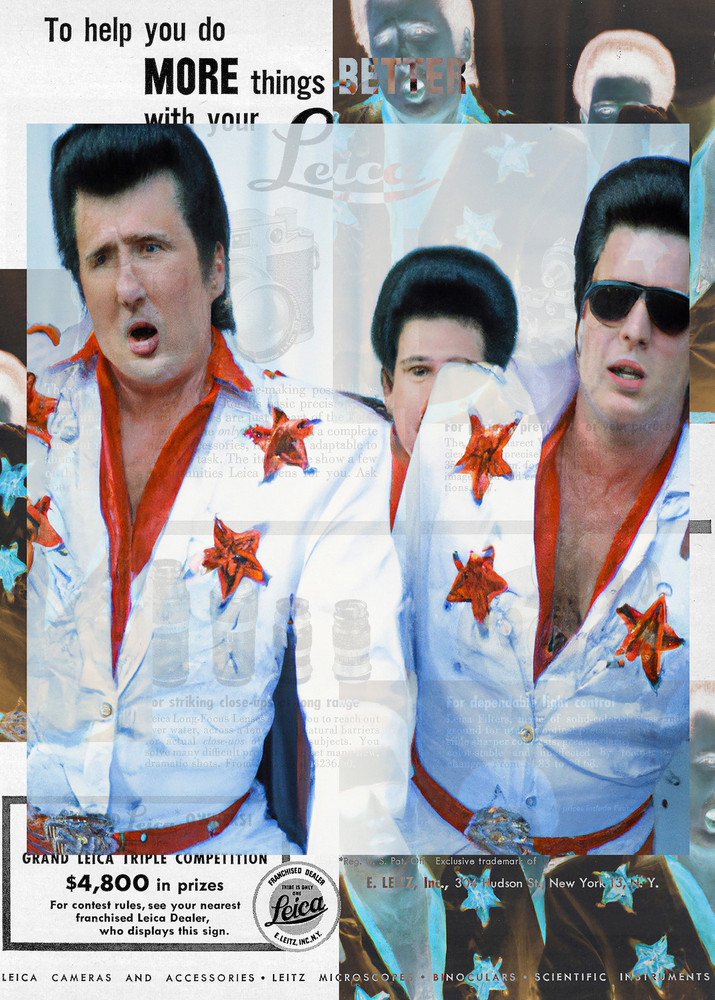

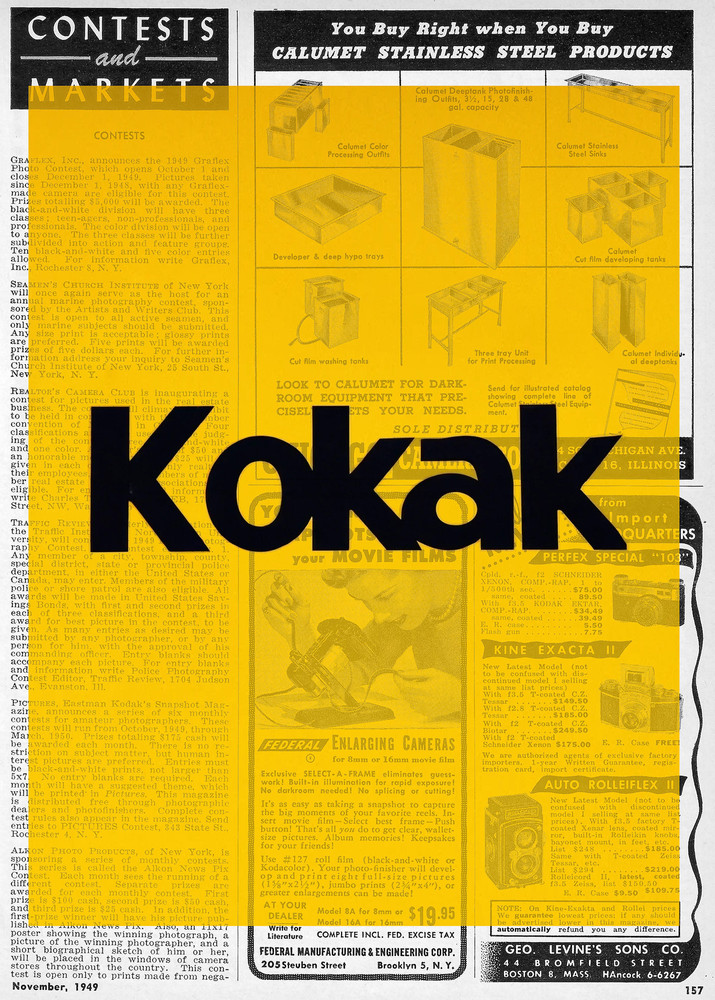

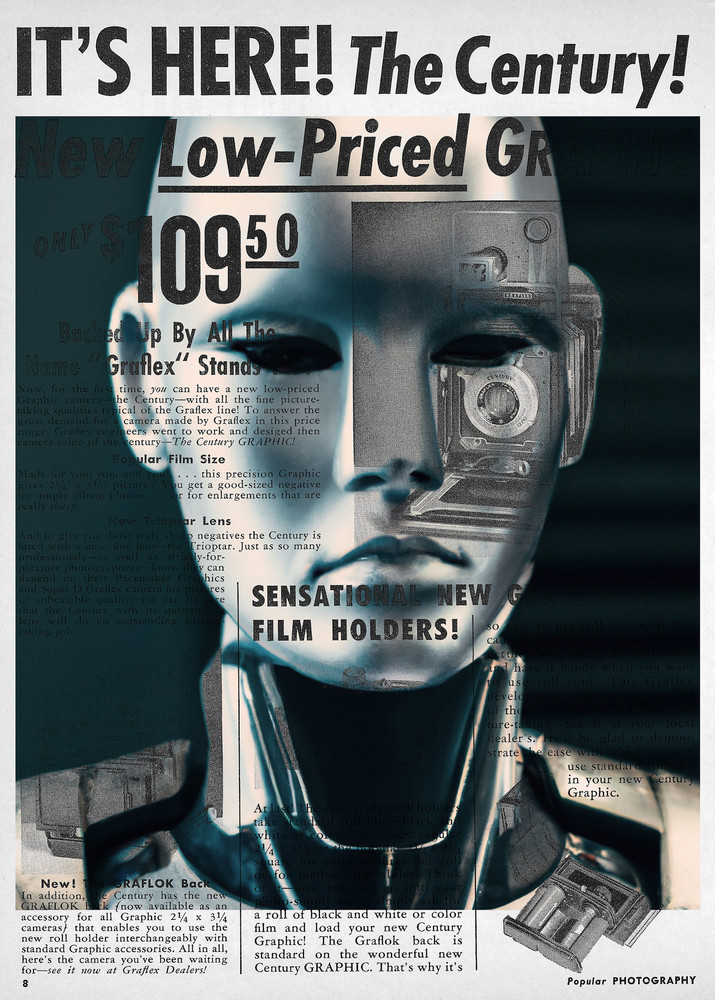

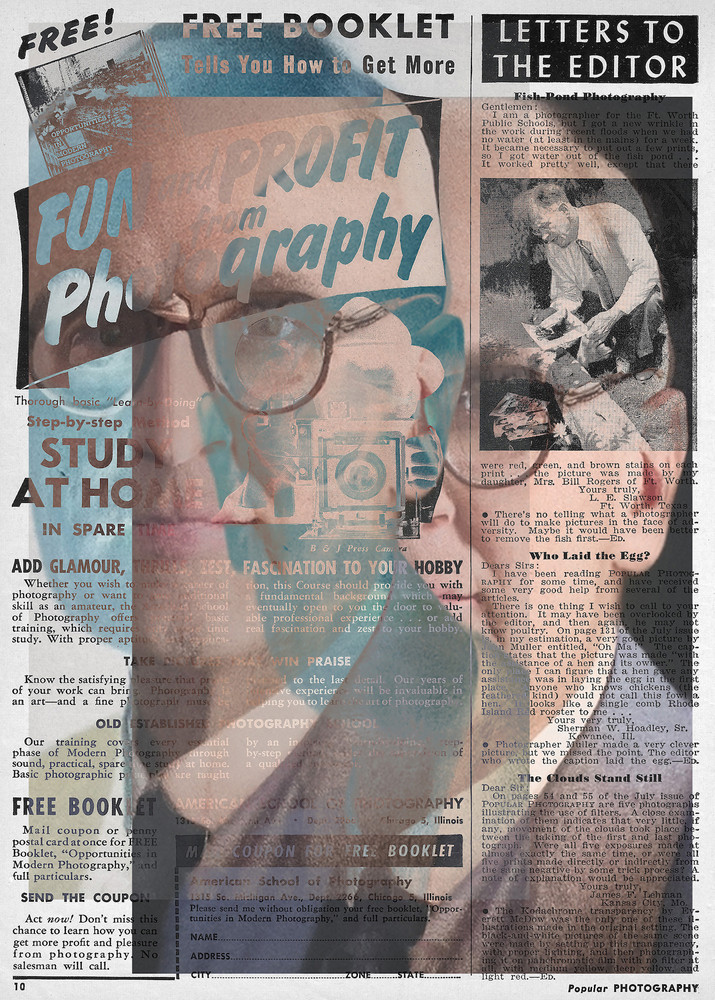

In his new body of work 49/23, artist Gregory Eddi Jones combines a vintage 1949 edition of Popular Photography magazine with AI-generated images. Through his collage process, he questions the evolving nature of photography and its impact on our perception of the world.

The series playfully draws on the historical importance of the American publication in the medium’s lifespan, bringing photography’s past into conversation with its present. The resulting images are built from text-based prompts that we’ll never see, pointing to the boundaries of interpretation and inviting us to consider the profound implications of a rapidly advancing technology.

In this interview with Liz Sales for LensCulture, Jones discusses themes of appropriation, the passage of time, and the complicated relationship between a photograph and its subject.

Liz Sales: What is the significance behind the title 49/23?

Gregory Eddi Jones: I combined pages from vintage 1949 issues of Popular Photography magazine with AI-generated images inspired by those same pages. AI image making tools are beginning to drastically change what photography is, and I wanted to find a way to form a conversation between new and old photography.

I believe there’s a fascinating link between AI and the more traditional photographic technology represented in the magazine. The title works as a timestamp marking the years of creation for both the source material and the images I made to collage them with.

LS: What prompted that idea?

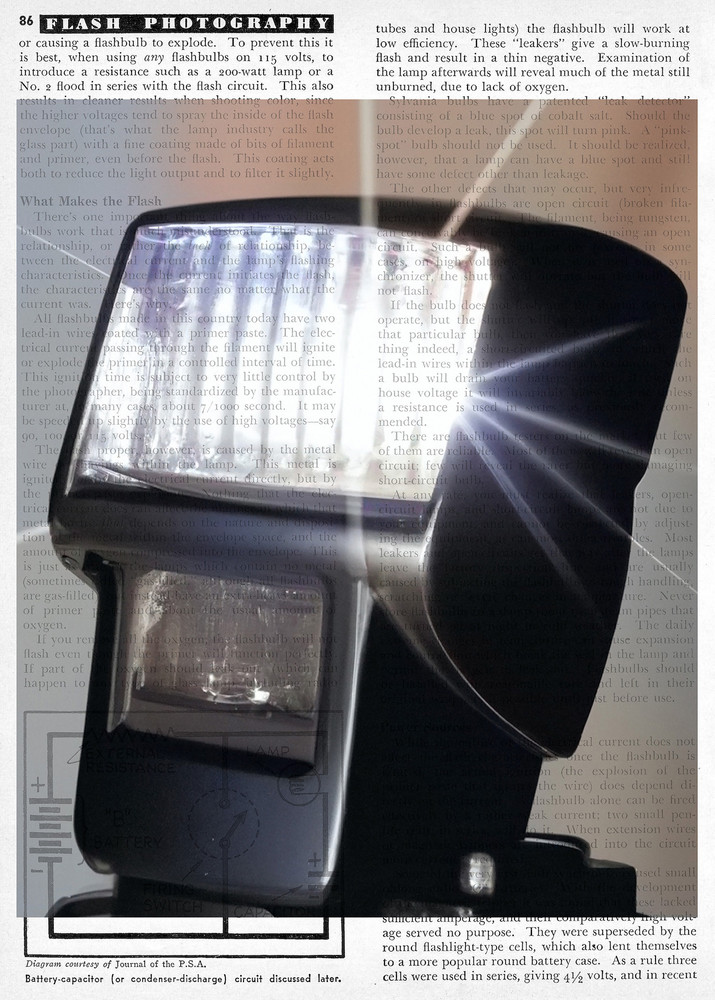

GEJ: A few years ago, I went to a library sale in West Philadelphia and found some old issues of Popular Photography. I bought them, thinking I could use them in my work. But they just ended up sitting on my shelf, untouched. Then, last summer, I became interested in using AI, but didn’t know where to start. I noticed that photographers are beginning to use these tools to make images that couldn’t otherwise be made without significant production value: science fiction, fantasy, or alternative history pictures with convincing veracities—I didn’t want to follow this route, and felt an urge to use AI tools in a more recursive, self-reflexive way. A lot of the pictures I was asking AI to make were of cameras and photography equipment as I was curious to see how well these picture engines understood their own technological lineage.

I was also interested in making really ordinary pictures that felt like they went against the spectacle of imagery that most seem to seek from AI. In exploring the tools in these ways, that’s when I remembered those magazines on my bookshelf, and thought they would be the right foil for considering the nature of AI and its photographic heritage.

LS: What was it about this 1949 issue of Popular Photography magazine that made it such a valuable resource for your AI experiments?

GEJ: Well, I am interested in the technological evolutions of photography, and a long-running publication like Popular Photography is such a valuable historical reference for tracking the medium’s technological growth over time. I also think that the magazine’s focus on “popular” photography—the accessibility of the medium to hobbyists—shares a lot of ground in how simple it is to use AI tools to make sophisticated-looking images. There’s a common space of deskilled craft that I thought made for an interesting place of reflection.

I also saw that issue as an opportunity to reflect on the incredible technological changes that can occur in a single lifetime. Anyone still living who would have read Popular Photography in 1949 are likely in their 90s now. Mid-century photography is now at the tail end of living memory, and it’s interesting to me to think just how image-making processes may very well be unrecognizable by the time we reach that age ourselves.

LS: Could you walk us through your own image-making process?

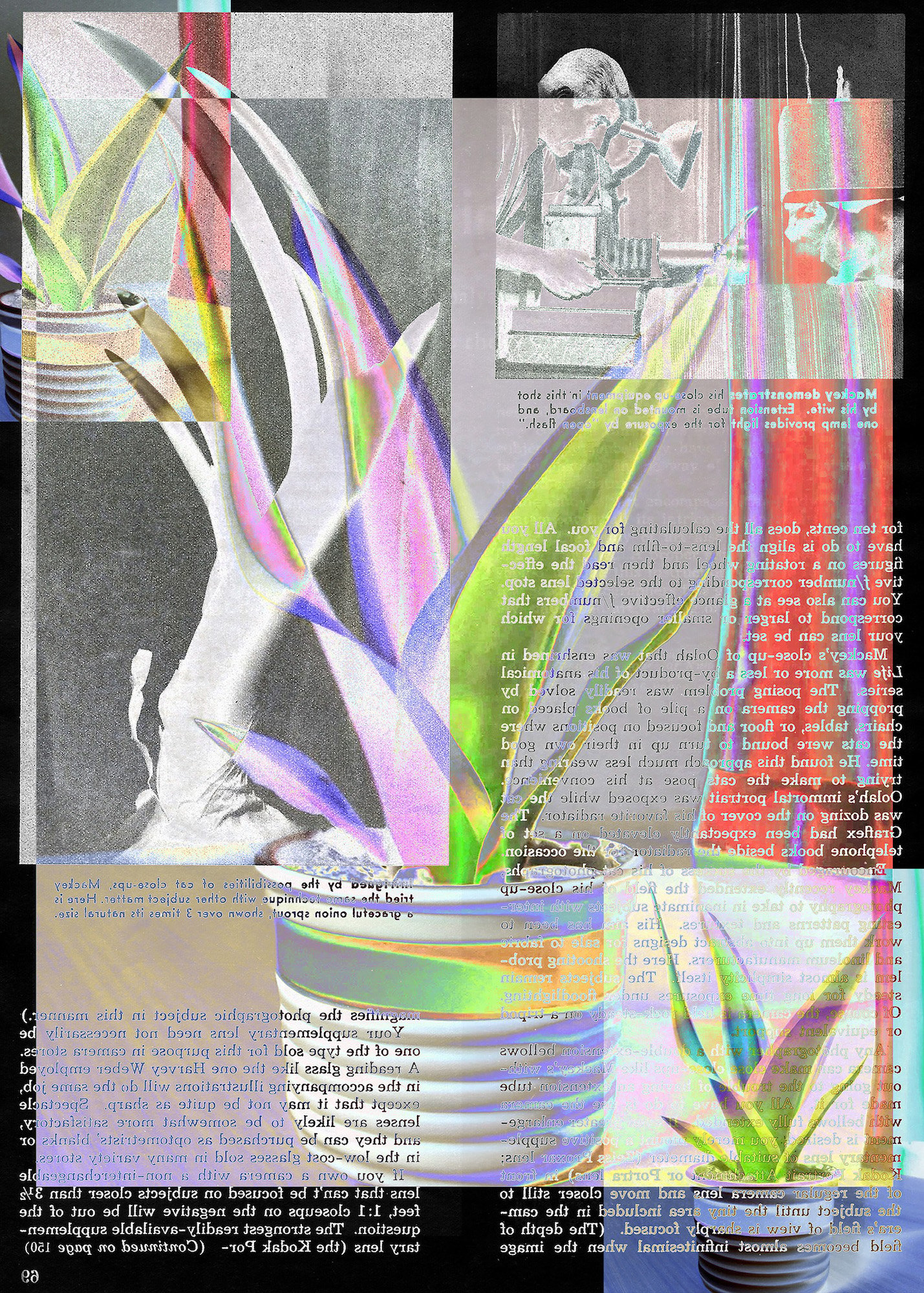

GEJ: A lot of the AI pictures are results from text prompts inspired by the actual content on the magazine pages, either snippets of text or interpretations of the original published photographs. In some way it’s giving the source material a certain degree of authorship. When I got image results I liked, I would collage them into the source page.

LS: What was your source image selection criteria? How do you think it reflected the concepts, ideas and themes you were addressing in this work?

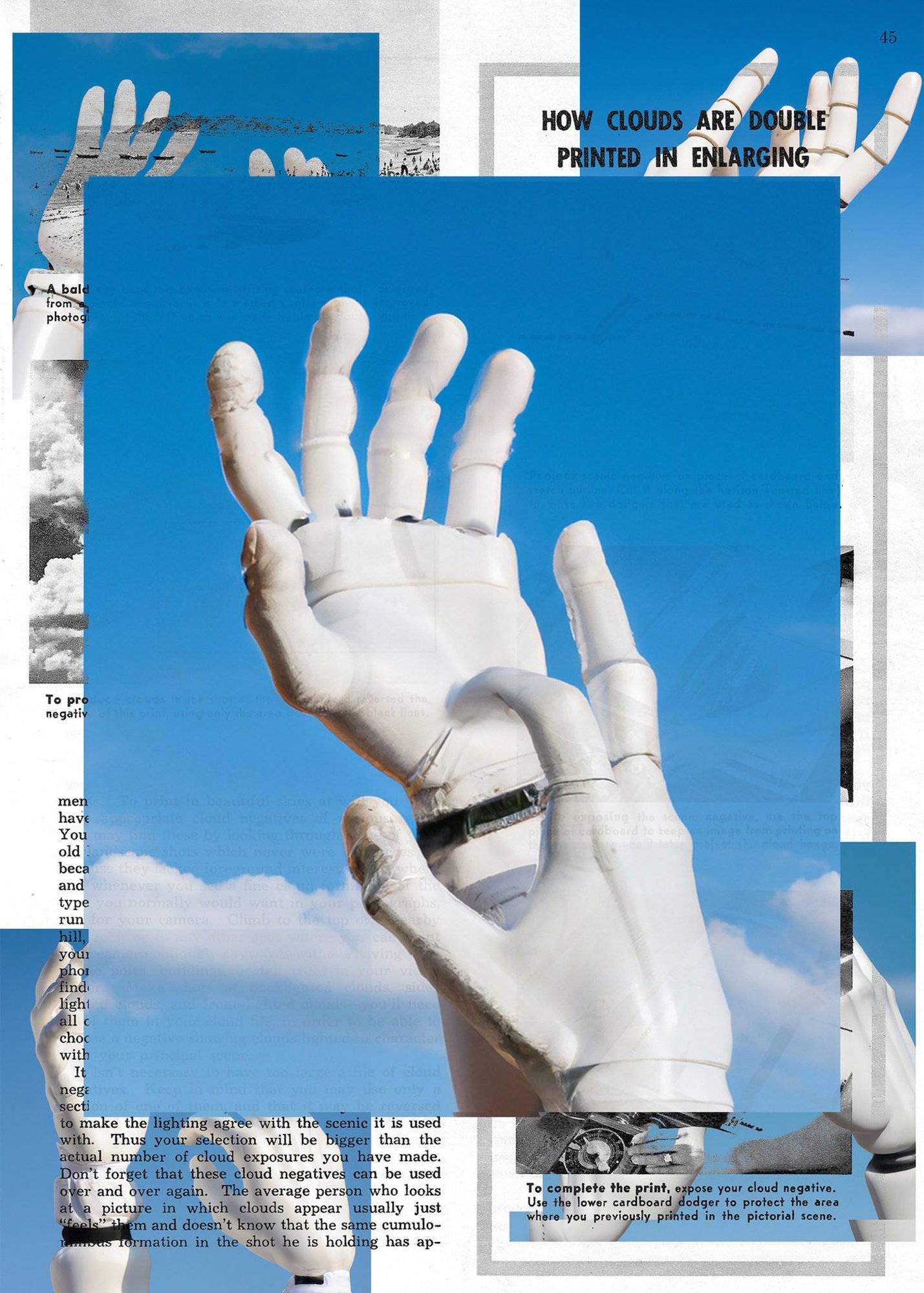

GEJ: So, when I started this project, I kept an open mind and let my instincts guide me. I found myself really drawn to certain image motifs. One of them was hands. They reminded me of the earliest forms of art, like the outlines of hands you see on cave walls. It’s so interesting to think of how the use of the hand has migrated from a tool of physical labor to instruments for creating art through typing on a keyboard. Another motif was the overall ecosystem of visual production. Pictures like assembly lines, factory buildings, workers, along with cameras, darkroom equipment, boxes of film, etc… all refer back to the deep well of product infrastructure that supports the advancement of the medium.

LS: What are some other image motifs you were drawn to?

GEJ: One of the main ideas in 49/23 is imitation. AI is like this engine of mimicry, and I liked the idea of using that to make images of things that mimicked other things. So in the series, there are subjects like an inflatable pool alligator, a rocking horse, a ventriloquist dummy, and Elvis impersonators, among other things.

LS: Some photographers often use text to give their images context, while other photographers more often use it to complicate the meaning of the image. You’re using text the viewer cannot see. Something is interesting to me about that. Could you talk about the concept of language in this project?

GEJ: A lot of my projects utilize text in one way or another. I like the depth that it adds. Words can be so powerful in shaping how images are read, and vice-versa. And of course, AI pictures are made with text prompts, which is such a perverse and fascinating method of image-making. For 49/23, I like how text and image inform one another. It’s this idea of the codex that just contains a lot of raw information to decipher. I often like making pictures that appear to be interfaces that viewers can interact with, like a touch screen or something. And maybe that goes back to this screen-mediated existence we occupy, where there are windows upon windows and all sorts of different information containers that we modify in various ways.

But in this work specifically, I like how the text performs as a time capsule. There’s a lot that’s still readable, and a lot that becomes obscured, kind of like building on top of an old, maybe crumbling foundation.

LS: AI programs like DALL-E use large datasets of existing work made by image-makers to learn from, raising a host of legal and ethical questions. Could you talk about appropriation, authorship, and the role of human creativity in this project?

GEJ: These areas are all part of the enormous amount of baggage that comes with AI tools. It will take a long time for us collectively to unpack it all, if we ever can. I’ve heard some people describe AI as the camera of the imagination. For me, art is an intersection of imagination and craft, and it’s curious to think what emerges when craft skill is no longer necessary. I think of AI image generation sort of like ordering fast food rather than cooking a meal yourself.

Of course, the broader implications of how these tools will change not just photography, but culture in general is pretty profound. I don’t know what computer-assisted authorship means for us; it’s still too big a question to get my mind around. I do know that like all technological revolutions in photography, AI use will receive a lot of pushback from those whose practices or perspectives on what photography is (or should be) become threatened by it. But we’ve seen this before when the digital camera was introduced to consumers. Photography’s legacy is a longstanding march toward greater efficiency, and AI is the latest checkpoint in that journey.

LS: You released this project as an NFT collection with Assembly. What is the take of the NFT world on your work? How is this environment similar to and different from your gallery audience?

GEJ: I think 49/23 was really well received when I released it as an NFT collection. It is a very different kind of audience than what is traditional in the photography world, and I think it’s a really interesting space to explore, especially for photographers who’ve been left out of the traditional gallery world. For me, it makes sense considering this sort of post-material/post-physical digital world we now occupy. It’s interesting because those involved with NFTs seem naturally more open to adopting new technology, and AI generated ‘photographs’ have become really popular in that environment. The immediacy of that culture, and the speed at which new ideas spring up, can be breathtaking.

LS: Would you like to show this work in a brick and mortar space? If so, how do you envision it installed? How would it function differently in physical reality?

GEJ: Of course! I am actually exhibiting a print from the work currently in a group exhibition at Assembly’s brick-and-mortar gallery in Houston. One thing that the digital world isn’t particularly well suited for is a sense of scale. So a physical installation of this work would certainly take advantage of that.

LS: Would you say the appeal of NFTs is more about owning assets that may accrue value rather than enjoying the images?

GEJ: Many NFT collectors genuinely appreciate artwork and build collections for personal enjoyment and the sense of community that comes with that. Many others in the NFT space are speculative and hope to resell artworks for profit. This speculative behavior dominates the majority of the NFT world, but to me it’s just a more visible mechanism of how art markets have always worked. NFTs have received a lot of bad press, but they’ve also opened an entirely new path for artists to sell their work that simply never existed before.

LS: I know collectors were buying digital art long before AI. However, I’m curious about NFT Art. When and how do we experience the work if it exists as a digital file?

GEJ: I think digital ownership is still a relatively new concept, but if you think about it most images are already made to be seen primarily on a screen, and I think the experience of viewing work in this context can still feel sacred in the right circumstances. It’s interesting because in the NFT space, collectors often have virtual galleries where they can curate and make arrangements of work they own, and without the physical limitations of space, storage and handling, it underlines how well images can travel and become mutable in digital space.

But in response to your question, I think the idea of making images specifically for the screen is really interesting to me. And part of what I wanted the images in 49/23 to do is feel like visual interfaces, or like products of digital mediation where we’re submersed in windows of data and words and images that are continually recontextualized.