In the course of just one week in a fateful late winter last year, photographer Hanna Hrabarska had to abandon her apartment, her photography studio and her childhood home. A horrific reality shared by the many Ukrainians who have been forced to flee their homes following Russia’s full-scale invasion on the 24th of February 2022, Hrabarska and her mother embarked on a journey from her native town of Kryvyi Rih to Uzhgorod, Mali Selmentsi, Kosice, Budapest and Munich, finally arriving in the Netherlands as war refugees.

Finding herself face-to-face with a new home and a new identity, Hrabarska picked up her camera on the first morning of her odyssey. My Mom Wants To Go Back Home is a moving documentary diary that charts the journey through the lens of her mother’s experience. The images born of this year of uncertainty—sometimes somber, sometimes humorous, always tender—grapple with uprooting and rerooting, focusing not only on leaving one’s home but also on what happens when we arrive somewhere else. The project is ongoing but will be published as a book later this year.

In this interview for LensCulture, Hanna Hrabarska speaks to Sophie Wright about the evolution of her photography practice, picking up a camera in the face of distress and finding the universal in the personal.

Sophie Wright: When and how did you first become interested in photography?

Hanna Hrabarska: Since I was 10 years old I dreamt of being a journalist. My life led me through lots of twists and turns; first I studied Law, but when I was studying, the Orange Revolution started in 2004 [a series of countrywide protests following a presidential election widely-seen as corrupt]. After it ended, I immediately started working as a journalist for a local newspaper in my native city of Kryvyi Rih. I was 18 and I had no experience but I had always loved writing.

After studying journalism in Kyiv, I started working for an NGO that was monitoring the political situation and the trustworthiness of politicians. It was at the time when we had a terrible president, Viktor Yanukovych who was very corrupt and suppressing freedom of speech. I filmed his younger son drunk on the street and published it. People started threatening me and I began to receive calls from the Security Service. Then my friend Mustafa Nayyem, who at that time was a famous journalist, told me to get a good camera so that if I witness something or something happens to me I can film it in good quality. In 2011, I bought my first camera and completely fell in love with photography.

SW: So your first encounters with the camera was as a tool to protect, to make documents.

HH: I began to take pictures when I started going to protests. When the Euromaidan Revolution broke out in 2013/14 [a wave of protests in reaction to President Yanukovych’s corrupt government and refusal to sign an agreement that would bring the country closer to the European Union], I was already freelancing for international media. But I was taking all sorts of pictures—from a little nice bakery to my coworkers to protests. I was always interested in portrait photography because my friends were always asking me to be their model, so I knew how that process worked too. I started to experiment with my girlfriends, as a parallel process; my reportage practice on one hand and on the other, beauty photography.

I wouldn’t say that I was accepted to the photography community immediately. There was a very patriarchal kind of way of seeing this role because it was mostly men. And if you were a young girl who has no experience but who says “I can do whatever you do,” they don’t like it.

SW: How did you get that experience?

HH: I just went out and did it. I think the Euromaidan revolution really helped me to gain a sense of professionalism. As one of my friends described it, it was one big photo laboratory where everybody was just training and experimenting and you were face-to-face with what was going on. When I look back at my archive, I can see that I was really learning to take portraits without realizing it.

There was an atmosphere of support and we photographers, working shoulder-to-shoulder, became very close. You’re a photographer on one hand, but on the other, if someone is in trouble, you help them. Someone is hungry, you bring food to them and then you go together to drink beer and edit photos. It was very communal.

SW: Tell me a bit about how your practice developed after that.

HH: I was working on my own photography, some side projects, I also work as a tour photographer which was my childhood dream. Then, in 2019, I quit my job with the NGO. I was desperate and I didn’t know what to do. I booked tickets to New York for two months and came back with answers. I always had a salary-kind of lifestyle and I didn’t know how to do things on my own, so I decided to go and see how people who were doing all sorts of things by themselves do it. When I came back, I started a project shooting portraits at home. I thought only my friends would come but then it became really popular, like four different people coming every day! So I had to take it to another space and during Covid, I found a studio.

SW: Were you still doing this project up until the moment that you had to leave Ukraine last year as a result of the full-scale invasion?

HH: Yes. I had the last shoot the day before the war started. Usually I would have the photos ready one week after, but this time they took me six months to edit the images from that day. I thought, if I send them then the history of my studio is really over.

SW: My Mom Wants To Go Home marks a rupture in your life and work, mixing the different threads of your photographic practice to respond to circumstance. Can you tell me a bit about what led to this project?

HH: Well, the invasion started in 2014 [when Russian troops invaded Ukraine in 2014, occupying Crimea, as well as parts of Donetsk and Luhansk, before the full-scale invasion of 2022], but I was living in some sort of aquarium. Even though many of my friends were fighting, I thought it wouldn’t go any further. On February 24, like everybody else, I was completely unready. I woke up from explosions—the most terrifying moment of my life I would say. You never know how you will react in these situations. But I started building a structured plan in my head. What were the ways to escape?

Since 2020, when I was in a car accident, my health and life became my main priority. My main challenge was to persuade my mom to leave. She was still asleep and I thought, OK, I have to make the whole plan so I bought all the tickets, she’d come to Kyiv and we’d go west from there. When she woke up, she refused to go because she thought that the connection would drop and we wouldn’t find each other. So I went to her in Kryvyi Rih. We volunteered for a few days and then there was an announcement that a big convoy of military vehicles were moving towards the city.

I gave my mom an ultimatum that we had to leave now. She agreed and we took a 24-hour train to Uzhhorod. I’m not going to complain about the train because compared to what people are going through in occupied cities or the people that cannot even leave—it’s unrelatable. When we woke up, I picked up my camera for the first time. I thought I would just distract myself by taking photos.

SW: What prompted you to document this experience during a time of such high stress?

HH: It was early morning. This was the route that we usually take when going on vacation to the Carpathian Mountains. I remembered from childhood waking up early to look through the window at these beautiful mountains and rivers. This time, we woke up early and we looked out the window. It was really beautiful, but in a completely different context. There was a mirror in the cabin that my mom was sitting next to. I decided to take a photo and capture the moment. And then I just kept taking photos.

When we arrived, I made a post on Instagram to share what was going on with my friends, not intending to make a story out of it. But people started sharing it, and then some media outlets approached me and asked me if they could use my story. Three articles came out with my interview and these photos. I began to see that this was more important than just for my family archive. Very quickly it was clear to me that I had to keep doing it.

During the first week, somebody wrote to me saying that they had seen my pictures. They said they hadn’t been able to relate to this war because they had never experienced it—it had just been a terrible event they saw in the news. But because everybody has a family, this person found a way to identify with what was going on. It felt important to show it from this perspective.

SW: It seems like at first, the images were an important way to keep close to people back home. But there’s a moment when they also begin to communicate with the new context you’re in.

HH: Even though the story that me and my mother are going through is not the most visually striking story, it’s happening on a mass scale. So many people left and are adjusting to a new reality. I’m not shooting a story about myself, even though I have my own feelings and things going on. I’m a more international person, I speak English, I have traveled a lot and can adjust to new circumstances.

But for my mother who has lived in the same city for 63 years, it’s completely different. There are so many people who have left their houses, who don’t speak the language, who never had to manage their life in this way and just had to leave everything behind and go in an unknown direction. So it’s a very individual story but at the same time, it’s very universal for Ukrainian women who have left their homes.

SW: Can you talk about what this very intimate collaboration with your mother was like?

HH: I’m very lucky that she is open and understands what I’m doing. When something happens with this project, she feels important and that matters as she doesn’t have much influence on her own life right now. I talked with her a lot about what’s going on and how this project can influence other people.

When I started publishing these photos, I asked her, “Do you mind if it’s going to be published in the news?” She said: “No, but don’t take pictures of me without a bra.” I could promise that! One website issued this interview and my mom was on the front page and under her was a picture of Joe Biden which I found hilarious. I sent a message to the editor, saying “Thank you for leaving some space for Mr. Biden!”

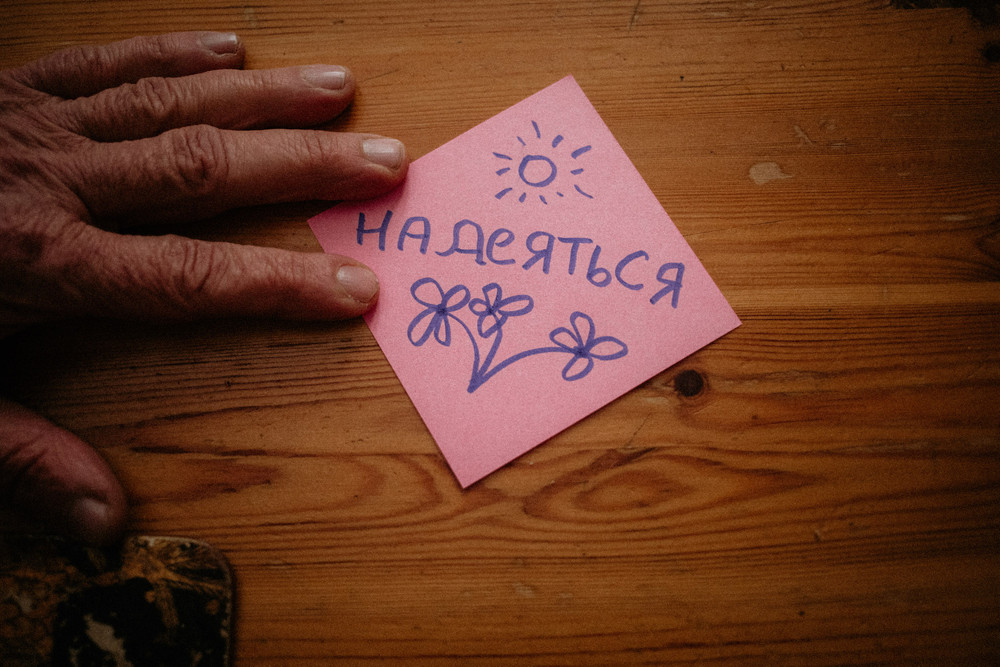

In the book she has her own chapter of photos she took on her phone. It provides a completely different perspective—my story is a big one in chronological order, but her photos are completely all over the place, very non-linear like how memory works. It’s mostly beautiful things like flowers and birds, events she went to, meetings with friends.

SW: Part of what moves me about this project is that you navigate the complexity of what it is like to land in a new place after fleeing. Can you tell me a bit about this part of your journey?

HH: On the one hand, you are unrooted from your normal life. On the other hand, you are put into a completely new situation in this beautiful country we now live in. In the beginning there was a lot of attention from other people because we were living in a small village, so everybody knew we were there. She got a lot of attention from different people so she made some friends. On the one hand it’s terrible, on the other hand it’s a good new human experience that she would never have been able to have if she was living in the same place. But she didn’t intend to leave. It’s not black and white.

There is no universal story. I have no doubt that leaving was the right decision for myself, even though I deeply respect those who stayed. During the first three months, I was desperately trying to persuade everyone I love to escape. And then I just realized that I’m disrespecting their decision. Some people might tell me to come back, and it would be disrespectful towards me.

SW: How did the project shift once you landed in a more permanent place?

HH: When we arrived, it was a big change of environment, mood, the feeling of safety and stability. I could observe my mom in a completely different environment. Before it was mostly really dark and sad, but it was a beautiful spring in Austerlitz and nature was blooming. It sort of moved from action to state, from “What do you do?” to “How are you?”

SW: The piecing together of everyday life when it’s been shattered. There feels like a weight behind the pictures.

HH: I want this project to be really truthful in a way that shows these parallel realities that are going on. I do see this experience of living abroad as very enriching for my mother. At the same time, I know how much she struggles because of this total disruption of her normality. I think one of the most painful moments since we left was less than a month into living in Austerlitz. The neighbor called my mom and said that the window in our apartment was open so we thought that somebody had broken in.

While we were waiting to find out what happened, we were so terrified and nervous, even though there is literally nothing valuable. What would they potentially steal? A TV or teapots? It was still so painful to think that while we weren’t there somebody had broken into the house.

In the end, we found out it was wind. Nothing was stolen. But I remember hearing my mom asking my brother to check on certain things to see if they were still there, for example, a cup that I brought her from Istanbul. I don’t even remember what is in my place. But for my mom, even that little cup was so valuable.

SW: You’re about to publish the project as a book. When will it end and what’s next?

HH: It’s a good question. Like the title, it cannot be finished before my mom actually goes back home, right? For the book, we decided to make the timeline the one year of being in The Netherlands. When it is released, I will still keep shooting but for me it’s important to have a kind of closure. I want to give it a physical form that will remain on people’s shelves. I think I will also be able to switch to other things that I want to do.

I want to shoot more portraits. I even bought a small camera to take away this burden of being a serious photographer. This is the first time when I don’t feel the necessity to prove myself anymore. The fear of a career move is tiny compared to what you’ve been through. I just want to live my life through the projects that I’m interested in, not just do it because I am a photographer and I have to do it.

SW: That makes it more like photography is a tool for living rather than an object that’s tied to a profession or a job.

HH: I also think that when you only focus on one topic it becomes too grave. With this project, I added some humor. It’s not just this woman that is living in her house, struggling. Obviously that’s there in the background, but at the same time, there is joy in life. There are some sequences where my mom is exercising. Before shooting, she said “Oh, I have to get ready. I will put on some lipstick.” They are funny pictures because she is really posing.

Everything is affected by Russian aggression right now. At the moment there is obviously no space for fun. But if you shoot a project for more than a year and you only find darker moments… It also affects your philosophy towards life. If you’re only looking for these moments, you don’t allow yourself to be open to a new situation. It’s a matter of survival; growing into a new situation and allowing yourself to take moments of joy.

I know people who lost their legs, arms, left or lost their homes and they are optimistic. If I shoot a book that is only full of dark moments instead of normal life, who am I trying to trick? It’s a war against the spirit.

Editor’s note: My Mom Wants To Go Home will be published by Jap Sam Books as a book, designed by MainStudio, later this year which you can pre-order here.