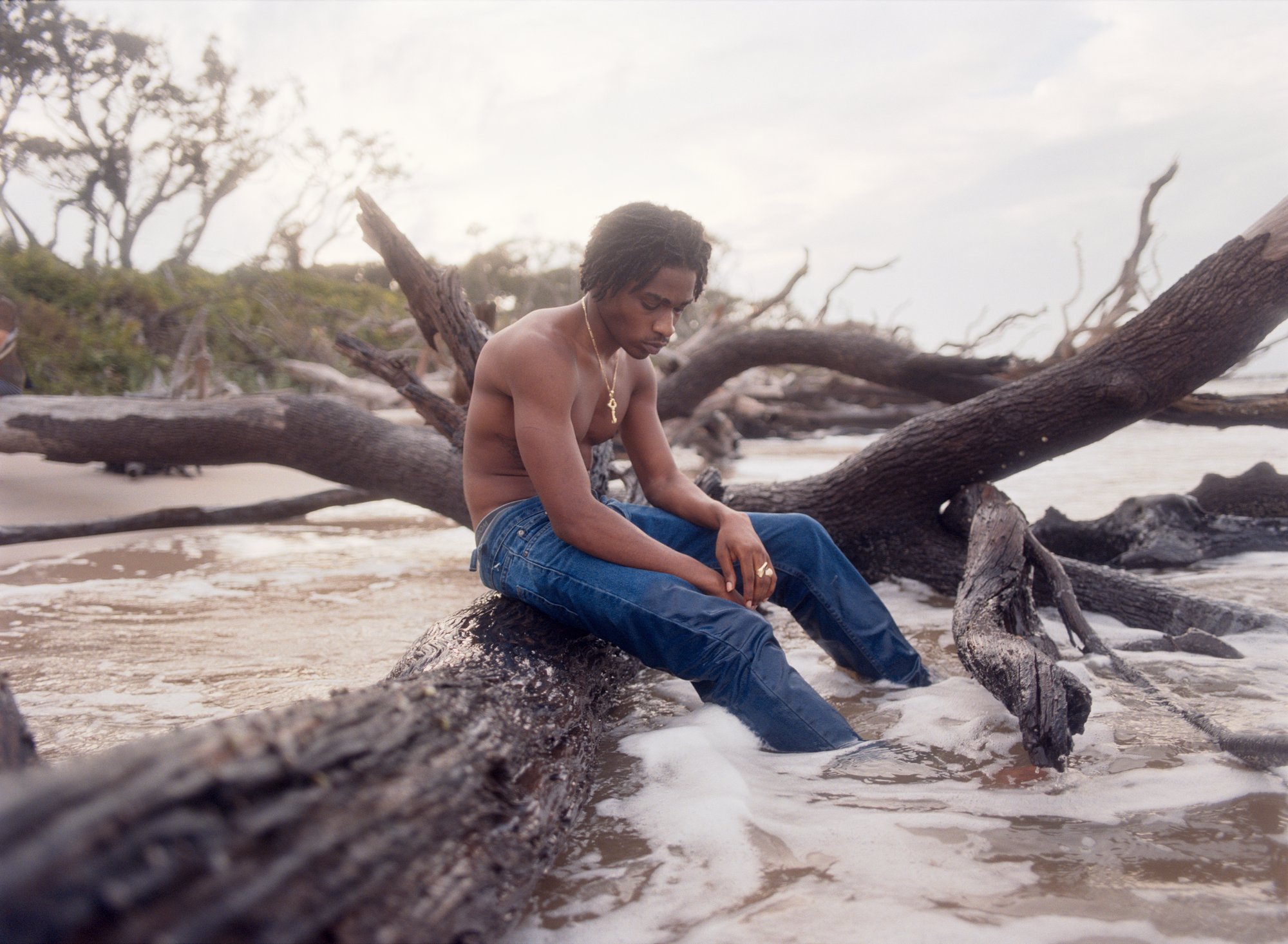

Much has been written about a crisis of masculinity in the past decade. Radicalization through social media channels, isolation, the proliferation of screens, and the near constant exposure to violence is hard to look away from. The notion of the hardness or strength in stoicism presents a narrow understanding of masculine expression. In Florida Boys, a series by Josh Aronson, these prevailing ideas are countered with another possibility—one of tenderness, vulnerability, and care.

Making his own mark in the lineage of tableaux painting and staged photography, he populates the landscapes of Florida with those who variously reflect his own experience as a first-generation, queer, young man of color; those too often relegated to the periphery of these stories, in states of repose and play. With influences from a broad array of sources—the archival images of a notorious reform school to the utopian imagery of the great outdoors and the dreamlike tones of coming-of-age films—Aronson’s idyllic scenes invite the viewer to reimagine what boyhood could look like.

In this interview for LensCulture, Aronson speaks to Magali Duzant about meeting the young men in his photographs, building a world of belonging and reimagining masculinity through a lens of tenderness.

Magali Duzant: Can you introduce yourself? What was it that first drew you to photography over other art forms?

Josh Aronson: I’m an artist living and working in Florida, and most of my pictures are about this place: its contradictions, its strangeness, its beauty. I came to photography through filmmaking. I wanted to make movies and picked up a camera to practice. But once I started photographing, I realized I could say a lot with a single frame. It was immediate. I began by documenting my friends, which led me to other artists, and eventually back to the landscape I grew up in: the South, in all its complexity.

MD: Within popular culture, there is a pervasive, conservative visual language of masculinity that is applied to the American South, dwarfing a vast array of lived experiences. When did you first become aware of this prevailing imagery, and how has it influenced your artistic practice?

JA: It started with literature. As a kid, I read Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston and A Land Remembered by Patrick D. Smith. Those stories painted men in the South as stoic, hard, almost mythic figures. Then came the movies: coming-of-age films that often centered white boys as courageous or introspective, while everyone else was rendered peripheral. I absorbed those images and realized how narrow they were. My work became a way of questioning them, of imagining what a different version of that boyhood could look like, one that includes tenderness, friendship, and vulnerability.

MD: What was the starting point for this body of work? Was there a specific moment that catalyzed the project?

JA: I wanted to reimagine coming-of-age from the perspective of the kids I grew up with, and from my own. So I started making pictures of it, not as nostalgia but as an act of invention. The project grew from that question: What could Florida boyhood look like if it were allowed to be soft, curious, even dreamlike?

MD: Your images have an immersive, cinematographic quality. Are there specific images, works of art, or other media that you are responding to or against or find yourself in dialogue with?

JA: I’ve always had a research practice. My references are broad: films like Killer of Sheep, Picnic at Hanging Rock, and The Virgin Suicides; 19th century tableaux paintings by Thomas Eakins, Winslow Homer, and Andrew Wyeth; and Florida folk traditions like the Highwaymen’s landscapes or Tom Gaskin’s cypress carvings.

I also look to the Florida School for Boys archive, a grim record of institutional life, as a counterpoint to what I make. In photography, I draw from Baldwin Lee, Mark Steinmetz, and the FSA photographers. And then there’s the lineage of staged narrative photography: Justine Kurland, Ryan McGinley, Gregory Crewdson, Jeff Wall. My pictures live somewhere in conversation with all of that, particularly Justine and Ryan, who I consider mentors of mine, and who paved the way for me.

MD: How do you find your subjects, and what is the conversation like when you introduce the project and your vision?

JA: Mostly through Instagram. I reach out to people whose aura I find interesting and invite them on a three-day-long road trip. At this point, we don’t know each other yet. They’ve seen my work and I send them a few references as well as asking for clothing sizes. We meet as a group and drive from Miami inland, toward the edges of the state. The road trip becomes our stage: it’s where we meet each other and get to perform this idea of boyhood together.

MD: Can you walk me through the process of making one of your images? There is a lovely, natural sense of choreography in these scenes. How collaborative are these? Do you sketch out your ideas before, or are you responding to the surroundings themselves?

JA: I scout alone first. I take notes, phone pictures, and sometimes make quick sketches of how I might block the scene. On the day, I show everyone the drawing, we try it out, and then we improvise. The best moments usually happen once we loosen things up… when someone proposes something unexpected, or when the energy shifts. I like to keep it open enough for that kind of discovery.

MD: In your statement, you write about an interest in “how the ideal unravels through repetition.” Can you tell me more about how this sense of repetition guides, shapes, or challenges the work and the concepts you are exploring?

JA: I’m chasing an impossible picture; the ‘perfect’ image of boyhood. But repetition exposes how fragile that idea is. The more I try to make it, the more it slips away. Over time, that failure becomes part of the work. Each photograph is an attempt to hold something fleeting, to see how the ideal starts to fray at the edges.

MD: In directing and staging these scenes, do you feel that you are creating an alternative vision or rather capturing what many fail to see for themselves?

JA: Both, probably. The Florida we usually see is hyper-sensationalized: Tiger King, ‘Florida Man,’ spring-break chaos. I’m trying to show something else. My images imagine a Florida populated by tenderness, empathy, and friendship. Is that a real place? Maybe not yet. But photography lets me build it; an alternate South that feels both familiar and aspirational.

MD: These are staged narratives, in which your subjects are performing, but is there a moment or a space as you photograph when performing shifts to experiencing? Or when the action steps away from performing and into an inhabiting?

JA: I hope so. For most of the guys, it’s their first time in these landscapes, so their reactions are real. They’re encountering the place, and each other, for the first time. Still, all social life is performance. We perform for each other, and for the camera. My goal is to create an environment immersive enough that, even briefly, that awareness falls away. For a second, the performance becomes a lived experience.

MD: As you’ve worked on these images, how has your own understanding or impression of the American South and of American masculinity (and the performance of it) shifted?

JA: Many of the people I photograph, myself included, didn’t grow up with what you’d call an ‘Americana’ childhood. Hiking, swimming in springs, camping: those things weren’t accessible to us. For a lot of first-generation city kids, nature didn’t feel like a place we belonged. Making these pictures has changed that for me. It’s taught me that belonging can be built, that you can photograph your way toward a kind of peace.

Editor’s note: Josh Aronson: Florida Boys is on view at Baker–Hall in Miami until November 22.