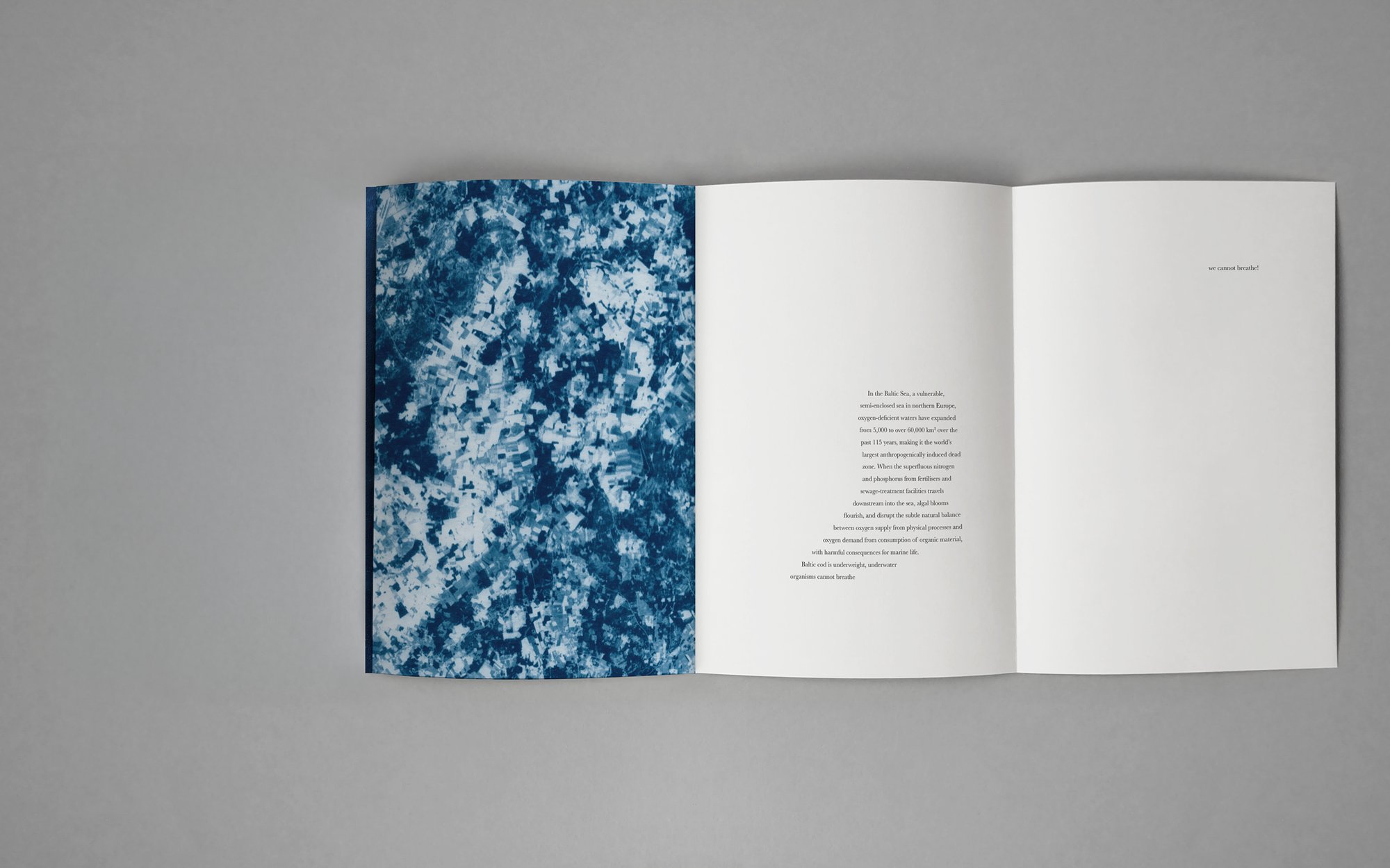

With each passing year, bodies of water across the world are becoming more and more oxygen-deprived. Rising temperatures combined with the destructive effects of human activities such as industrial agriculture and fossil fuel use has resulted in an increase of algal blooms, whose life cycles use up available oxygen to decompose, causing an existential threat to marine life. These oxygen-poor ‘dead zones’ are blooming across the Global north with cases doubling each decade since the 1960s.

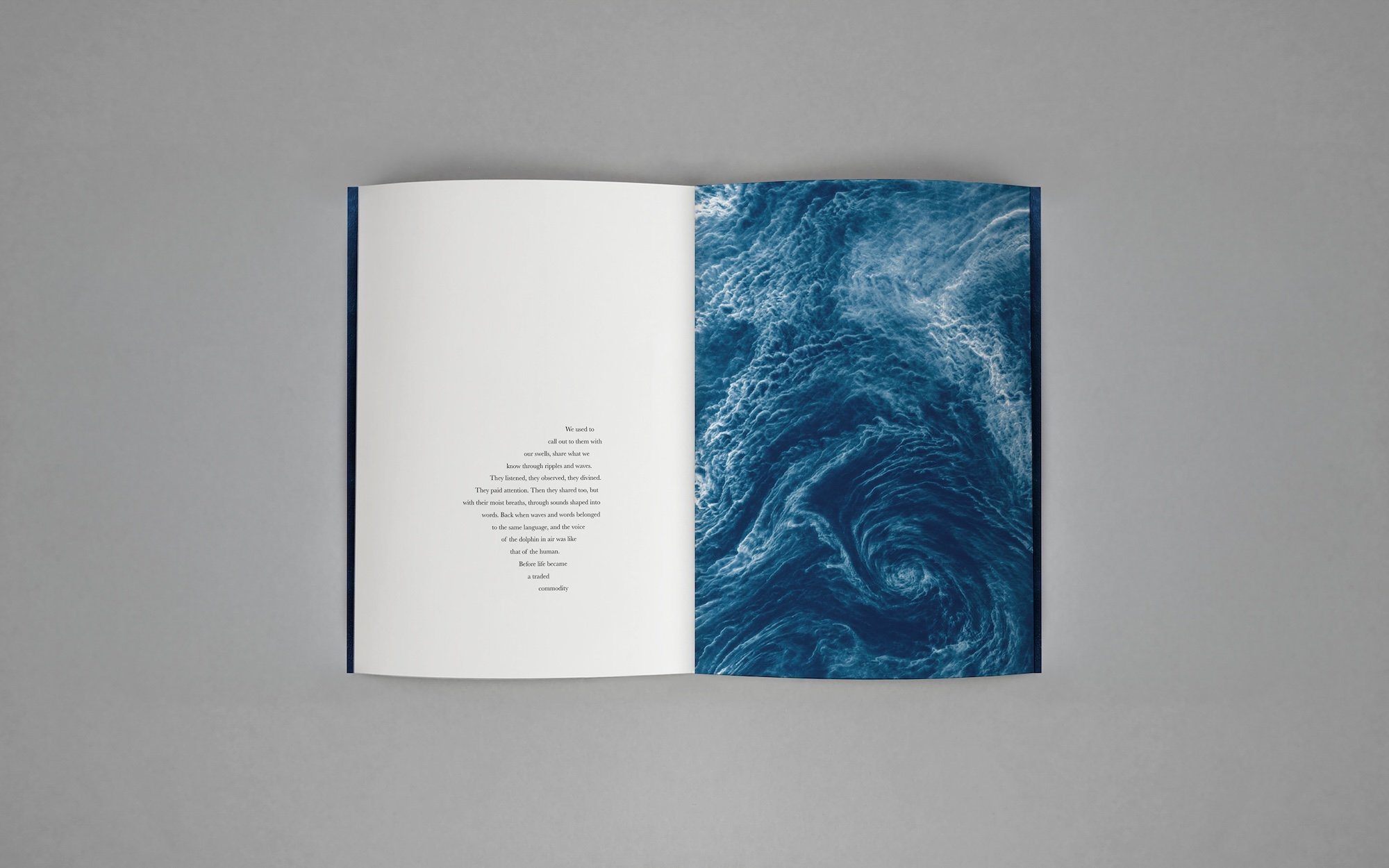

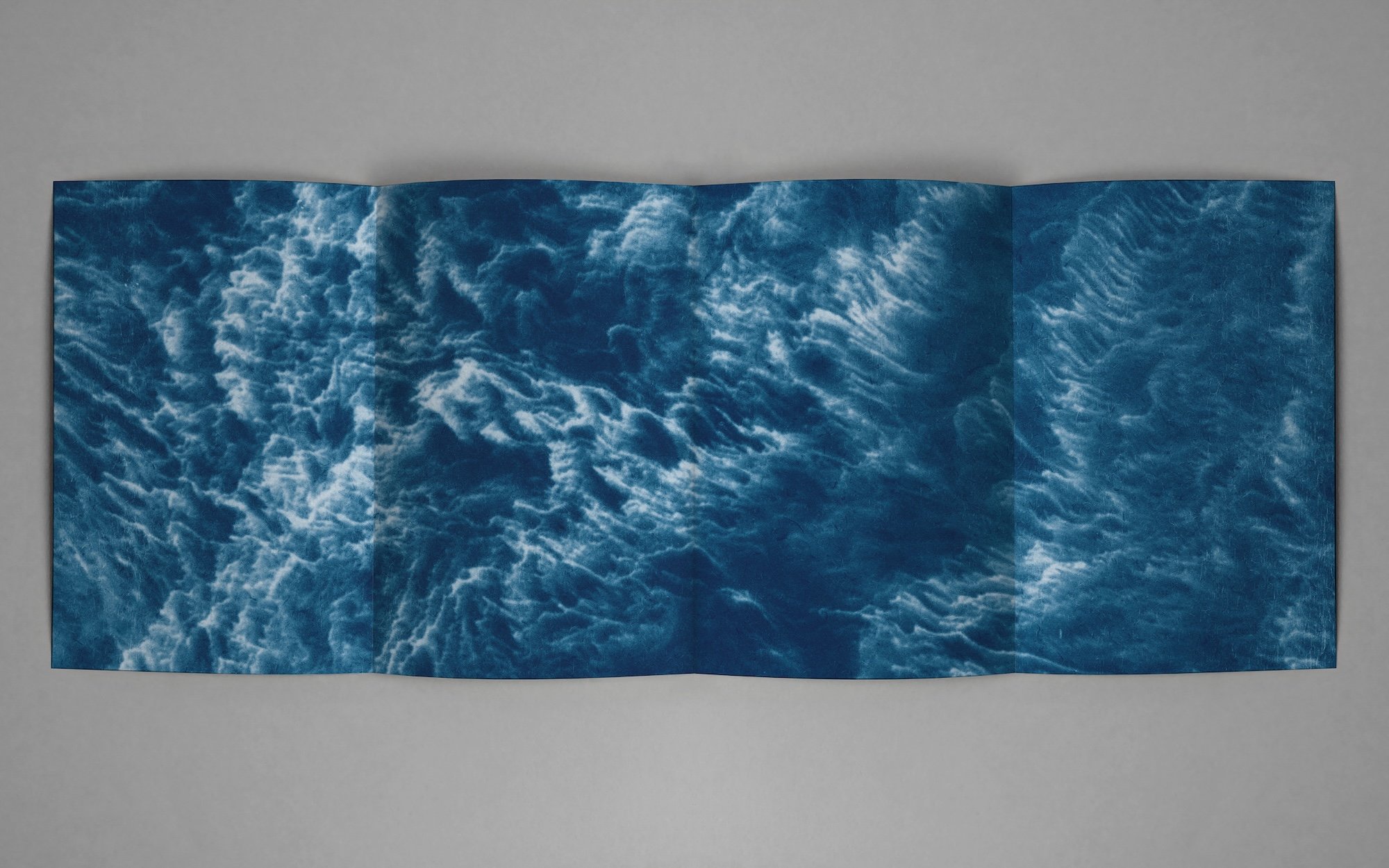

Concerned and curious by the silent and largely invisible phenomena unfolding in the Baltic Sea that she grew up next to, Małgorzata Stankiewicz set about trying to visualize a response. A fluid research process took the artist down the path of both image and text that come together to form ”viridescent, afire.” Her material experiments that translate remote-sensed images captured by NASA and the European Space Agency into cyanotypes sit beside free-flowing prose that draws on many texts from a wide variety of sources spanning the realms of science, myth and psychology. A tactile, non-linear publication that invites readers into humanity’s many attempts to chart these mysterious waters, the book explores a chorus of different voices that tell the complex and disturbing story of aquatic hypoxia—and the role of human activity in its escalation.

In this interview for LensCulture, Stankiewicz speaks to Sophie Wright about moving from journalism to photography, finding ways to draw attention to and articulate our place in a bigger web of life and the process of making “viridescent, afire.”

Sophie Wright: Do you remember the moment you first came to photography?

Małgorzata Stankiewicz: I just rediscovered the physical remnant of this story. I grew up in Poland in the 90s and at one of the first summer camps I went to around the age of eight, my parents lent me their point-and-shoot camera. We went to the Tatra mountains—the opposite end of the country to where I grew up. I remember waking up before everyone else around the break of dawn and looking down from the balcony of the wooden hut we were staying in. There was a woman milking a cow and the clouds were backlit by the sun. It was such a numinous and still moment and I pressed the shutter. When the film was developed, I remember seeing this picture and being transfixed by how it captured what I felt—even though the image itself is so mundane. But for me it really felt like I was able to capture some essence of what I had experienced.

Many years went by and I didn’t pay so much attention to photography. Then, when I was studying journalism in London, we had to choose an elective and I chose analog photography. I was in the darkroom for the first time getting my hands into developer—the whole process felt like magic, how an image just appears like that. Some six years later I found myself at ICP in New York enrolling to their alternative photographic processes program where I experimented with practices such as platinum and cyanotype. I really enjoy this haptic element that adds impressionism to the picture. I’ve never been interested in depicting things in a realist way, it’s also always about conveying this emotional layer.

SW: How would you describe the questions that you’re grappling with in your projects?

MS: Reflecting back, I’ve always been interested in what Western culture considers to be the place of the natural world—this superiority we have over it. Well, it’s actually much more complex than superiority; living in a city, we can read all this great theory about the interdependence of all life, ecology and the need for sustainability but it’s not a felt experience. Whether it’s due to this formative experience of taking the mountain picture or spending summers in the forest, I’ve always had the feeling that we’re truly embedded in the web of life. I want to use my work as a tool to create a space where these two worlds of science and felt experience can somehow overlap, so that maybe someone who is looking at it will pause and reflect. It’s not about didactically informing people—we have enough information already that is clearly not doing anything. I have this way of reading and being curious that leads me into so many rabbit holes. Somehow I manage not to get lost and I feel that’s a strength of mine to connect different strands and share them.

SW: A lot of your previous work has circled around our relationship to the environment. There is a focus on quiet, imperceptible and slow catastrophic things that are happening to our surroundings that we can’t really see or grasp yet. You’ve mentioned that we’re exposed to so much information but it’s not really effective—is your approach in response to this?

MS: It’s a good question. It’s a fine line. I realize that sometimes I used to put too much pressure on trying to achieve something with the work. With cry of an echo [a book made in response to the Polish government’s announcement to allow large-scale logging in an unprotected area of Białowieża Forest] I was so distraught by what was about to happen to this forest I ended traveling to and spending a month in after reading the news. I felt this urgency that the book had to wake people up and stop this atrocity from happening—which obviously didn’t happen. That can take a big toll. It’s not that I am cynical or disillusioned; it’s more that my intention is to create an opening for something else to enter. I am not necessarily trying to impose a new way of thinking, feeling or relating to the situations I am working with but rather to bring these subjects into focus and create a space for other voices to have a seat at the table—to counteract a monolithic way of telling a story. And hopefully one of these many voices or modes of expression will speak to whoever is experiencing the work.

SW: How did you come across the news that this forest was going to be destroyed?

MS: It was through the Guardian. It was similar with viridescent, afire where I read about the dead-zones of the Baltic Sea. Since I grew up close to the coast, I remember every year there would be seasonal algal blooms that meant you couldn’t enter the water. So when I read about the extreme proliferation of this problem—and how it was so present yet so invisible—I was curious how I could photograph this phenomenon. The scientist I met with at the beginning of the project told me “you can’t” because it is underwater and it’s invisible. This is probably why we don’t really hear about it. In such a visual culture, if something is non-representable through a photographic image then it is easier to leave out of consciousness.

SW: What grabbed you about the algae story and how did it develop?

MS: I read about this phenomenon and how large and damaging it is and yet nobody is speaking about it—and that’s already enough for me. I was struck that it wasn’t being addressed. These kinds of stories don’t usually make it to the news, and if they do, the articles tend to be either sensational or brief. I contacted a scientist with whom I could discuss it a bit further. My mother is a scientist so I’m used to suffering through reading scientific papers because she would ask me to translate them into English. I have the capacity to understand them, even though it’s torture for me as the language is so dry.

SW: The form of your work seems very related to the content. How did you start using Cyanotype?

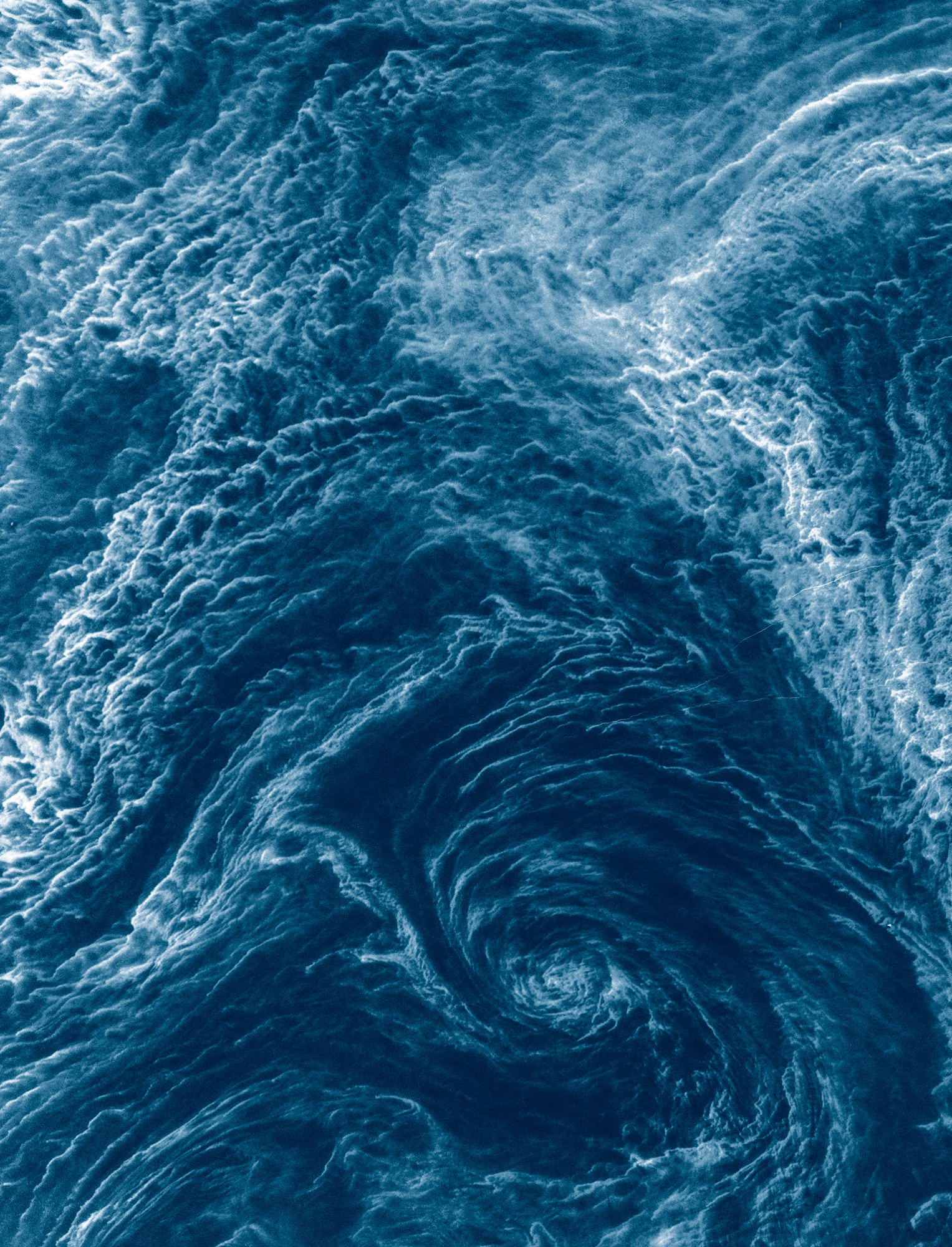

MS: I’d previously been working with the color chromogenic process by hand and it really impaired my respiratory system as it’s very toxic. So this time I thought I can’t use these toxic processes to talk about that very problem—injuring bodies whether it’s our earth body or my own body. Despite its name, cyanotype is the least toxic of photographic processes. It also seemed so fitting because of the cyanobacteria that makes up a bloom of algae and of course the color.

SW: Tell me about the process of translating data into images.

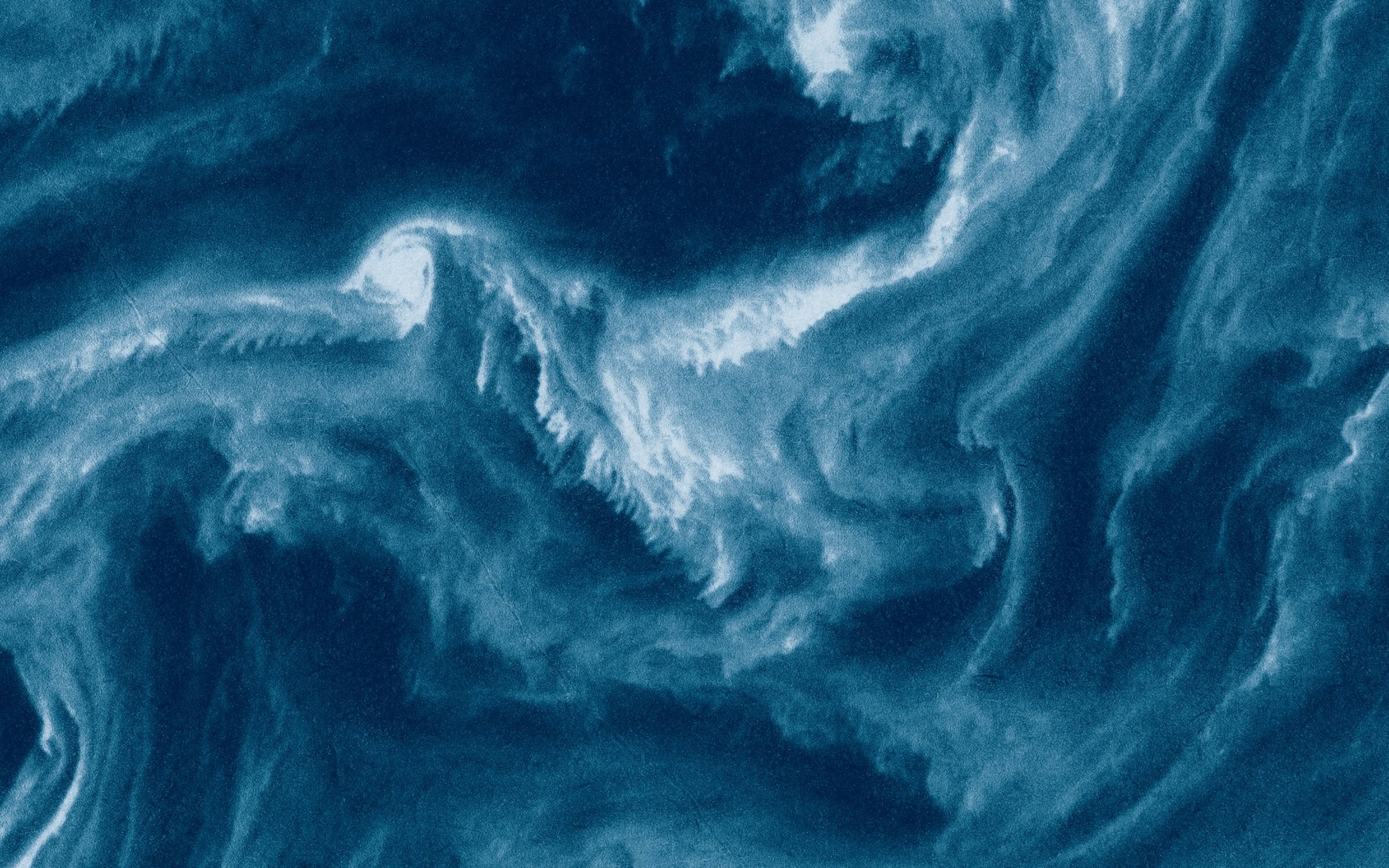

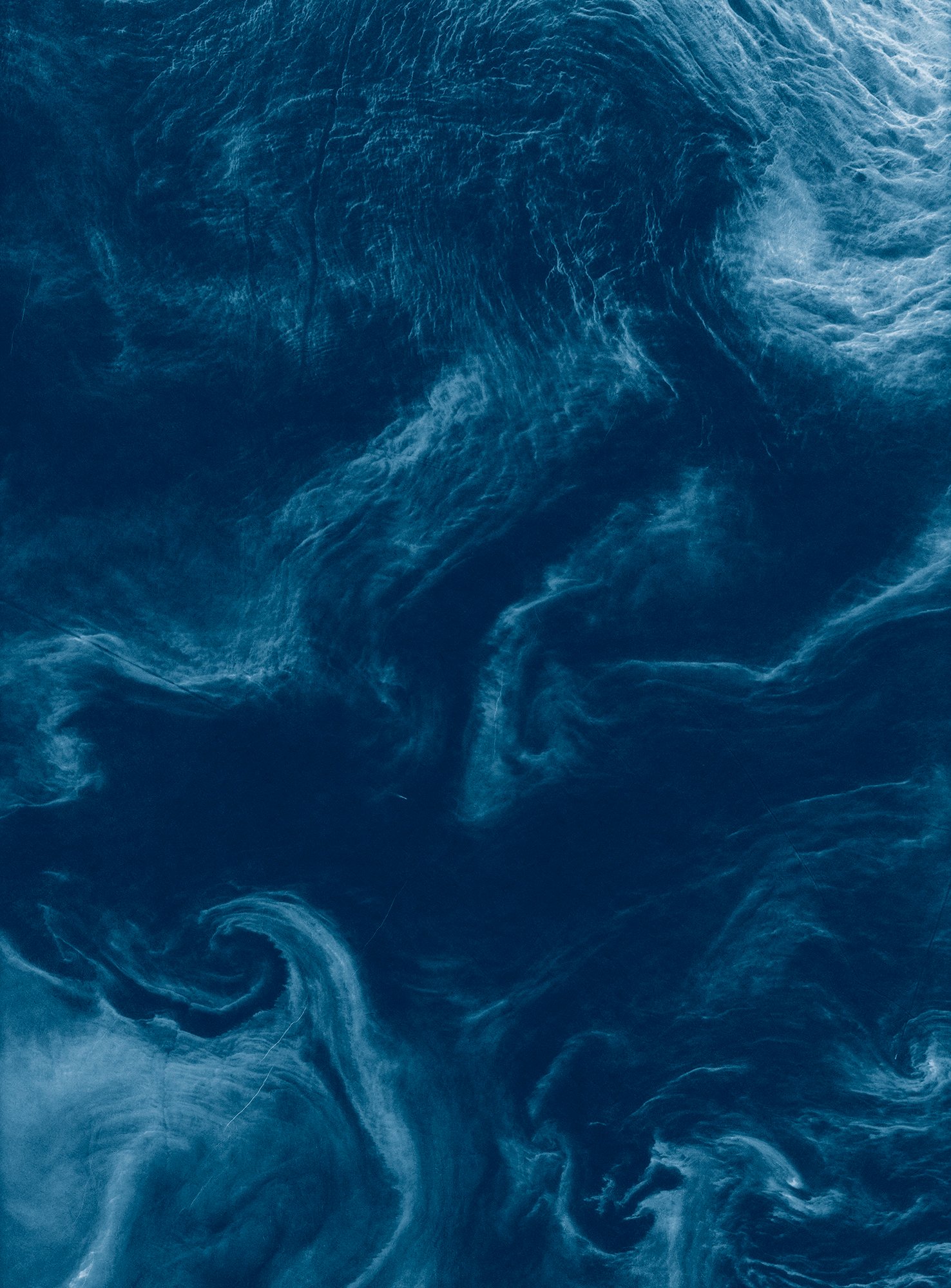

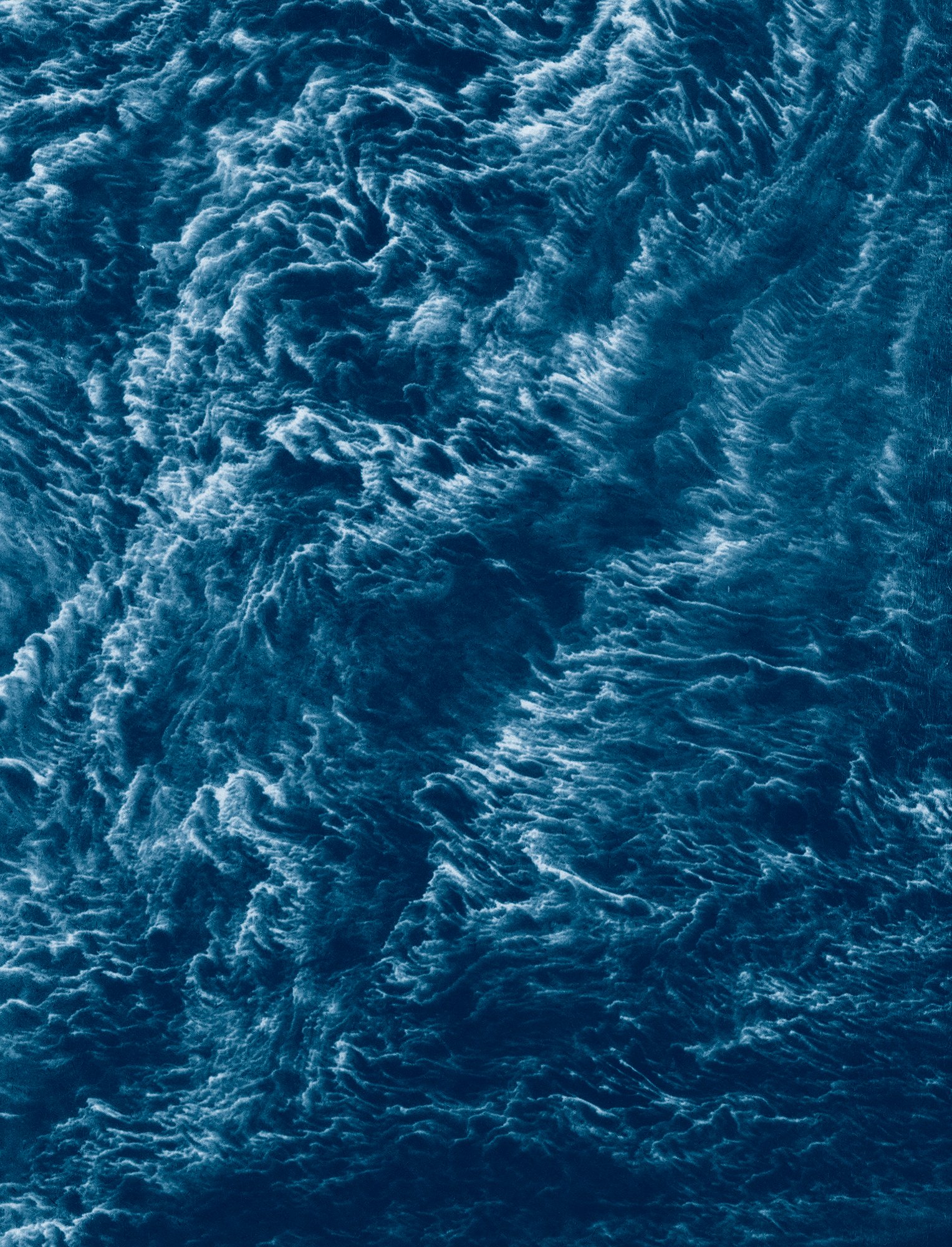

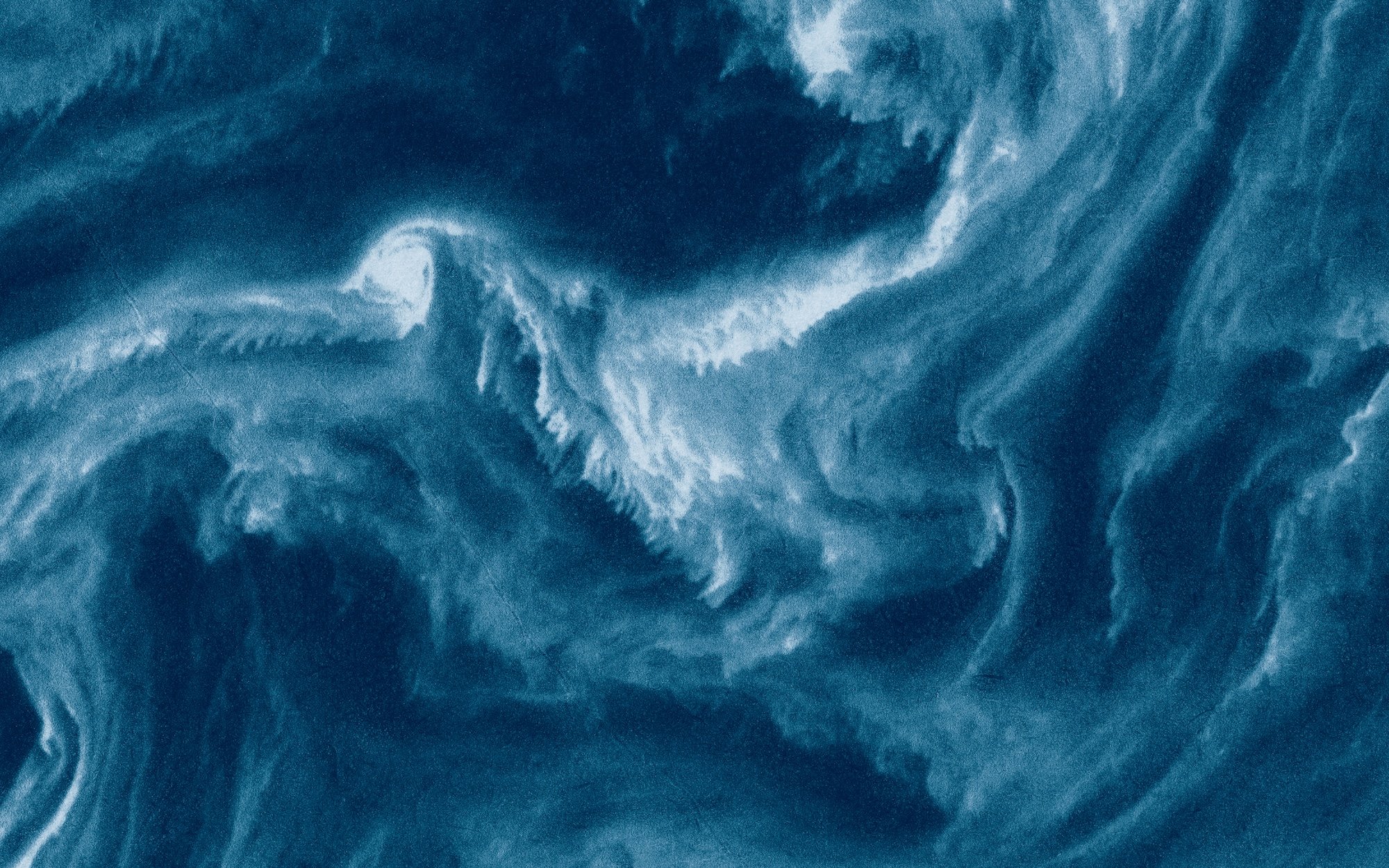

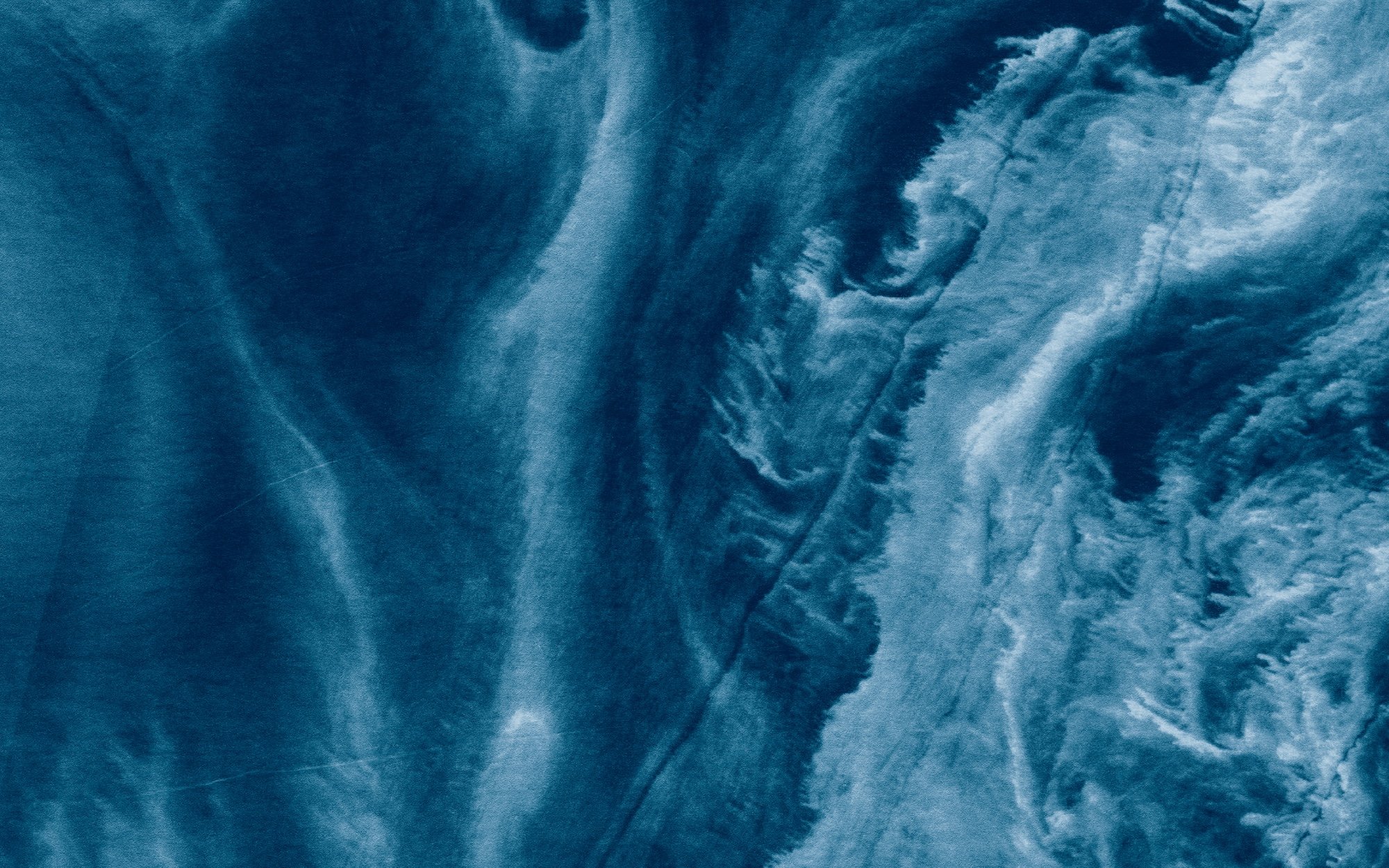

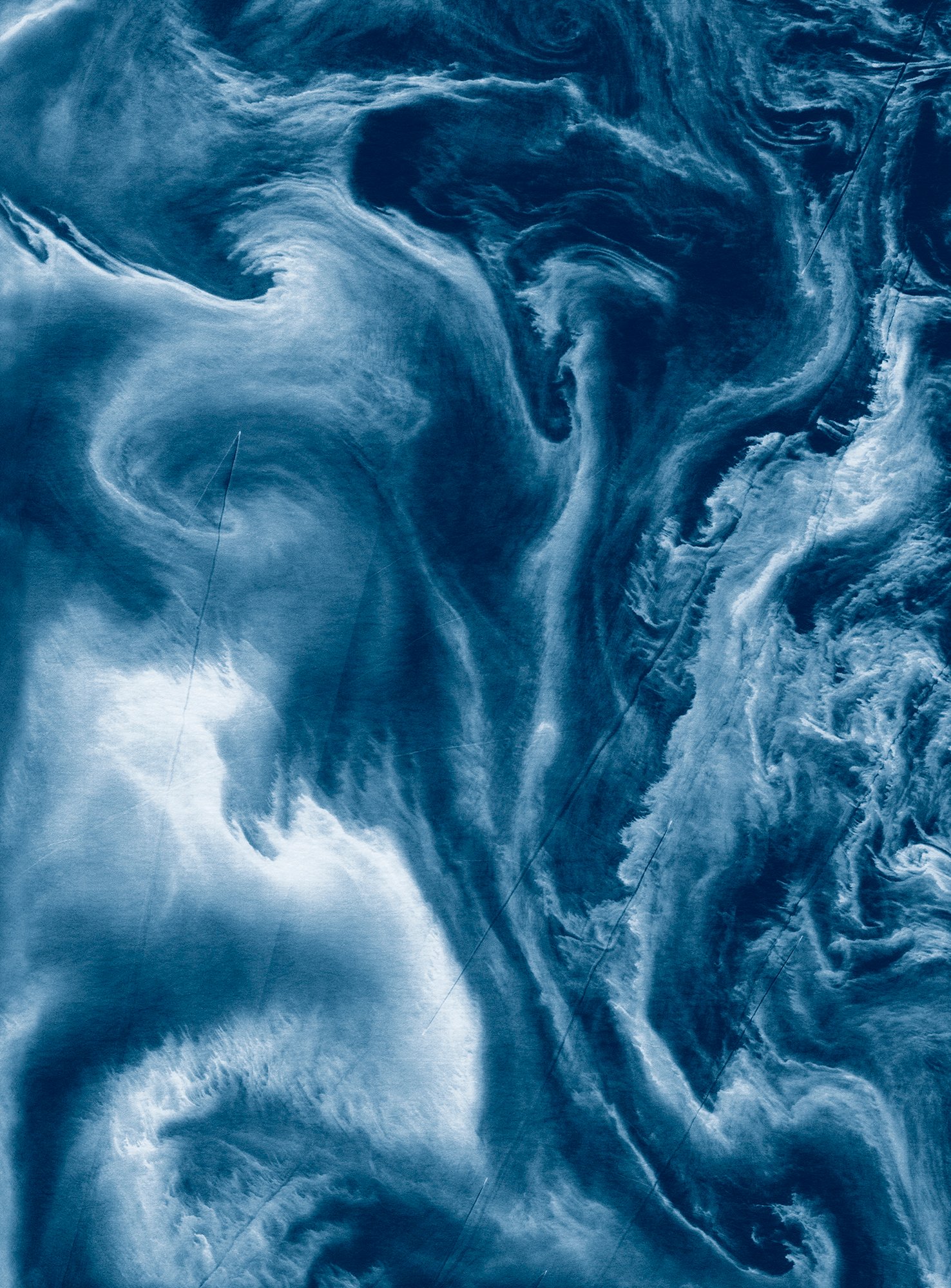

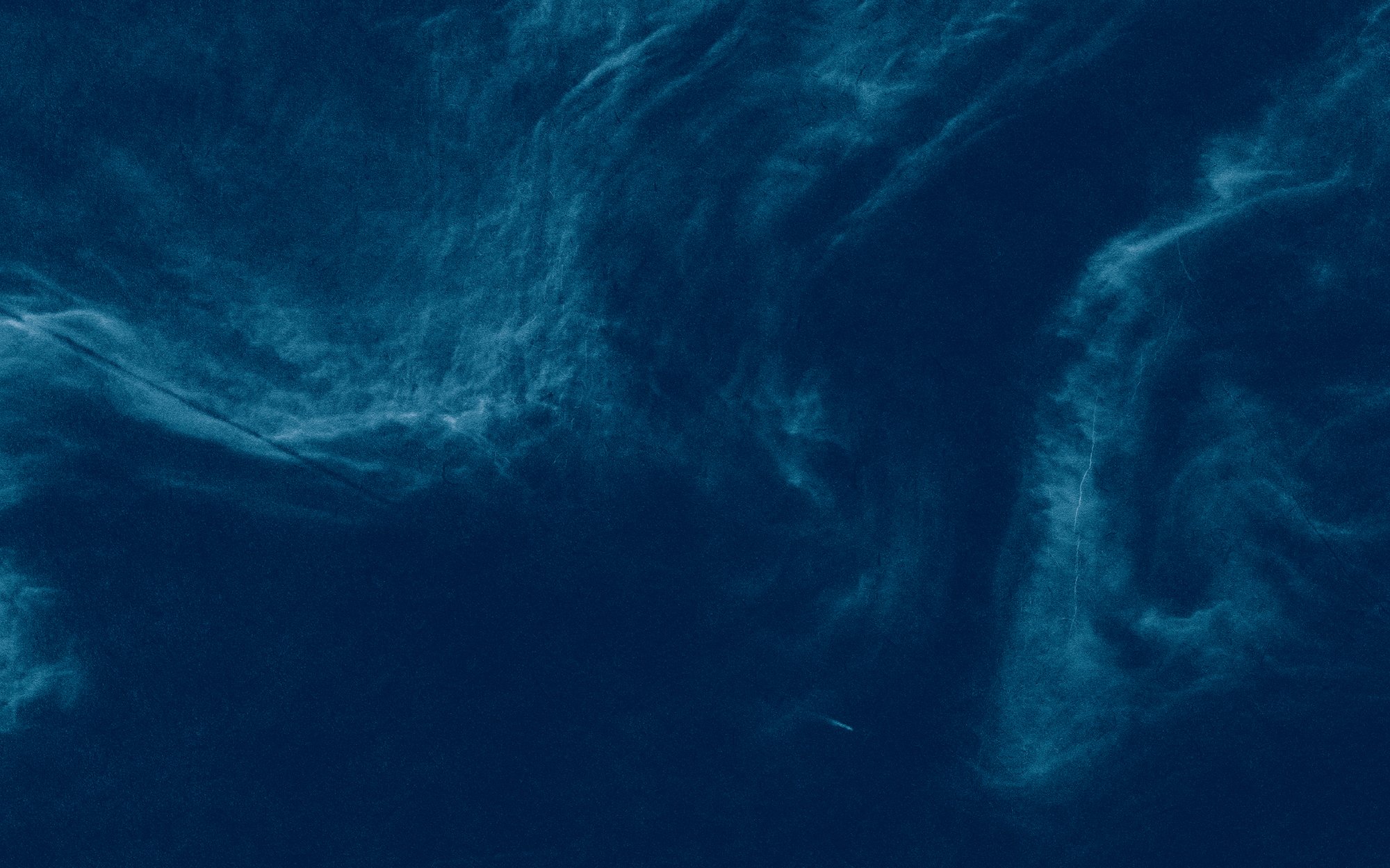

MS: As the phenomenon is invisible, the only way it manifests itself every so often is through an appearance of these algal blooms—but they are so vast that there is no way to grasp their enormity unless you look from a distance. I didn’t feel like renting a helicopter so I thought, why don’t I try to translate some images from NASA’s library into digital negatives? In the end, the whole book is made from only two images—one from NASA and the other from the European Space Agency.

I cut one image into nine, the other into twelve, then converted them into digital negatives. I was so fascinated by the amount of detail within these scientific images and there was a lot of dexterity involved in converting the digital files into printable negatives to maintain the resolution. The final files are huge because I made A3+ prints on Japanese sumi-e paper which I then scanned one-to-one. The project became very delayed due to the pandemic and other unforeseeable events in my personal life and I was slightly concerned that there would be some new developments that would make the work outdated but if anything it became more and more topical. Just this summer we had even larger algal blooms in the Baltic, vaster and larger in number. The final images are quite painterly, and there’s this chasm of them being poetic and beautiful—but we’re actually looking at something destructive.

SW: Sitting with just these two images is an interesting counterpoint to the speed of information that we’re usually dealing with. They don’t really impact your understanding of how this disaster is slowly but steadily unfolding.

MS: Especially because there is such an inundation of images. It feels very disposable. I really wanted there to be space around the text and images within the book. It’s about being almost at the edge of how long one can sustain a reader’s attention. I enjoy exploring and stretching that, and maybe also sometimes losing that grasp. If there was one thing I could protest on the streets it would be about slowing down. Sitting still for a moment.

SW: The text that accompanies the cyanotypes shifts between all of these different registers, unmooring the reader from one narrative. You’re dipping in and out of many things and sources. Could you talk about how you gathered it?

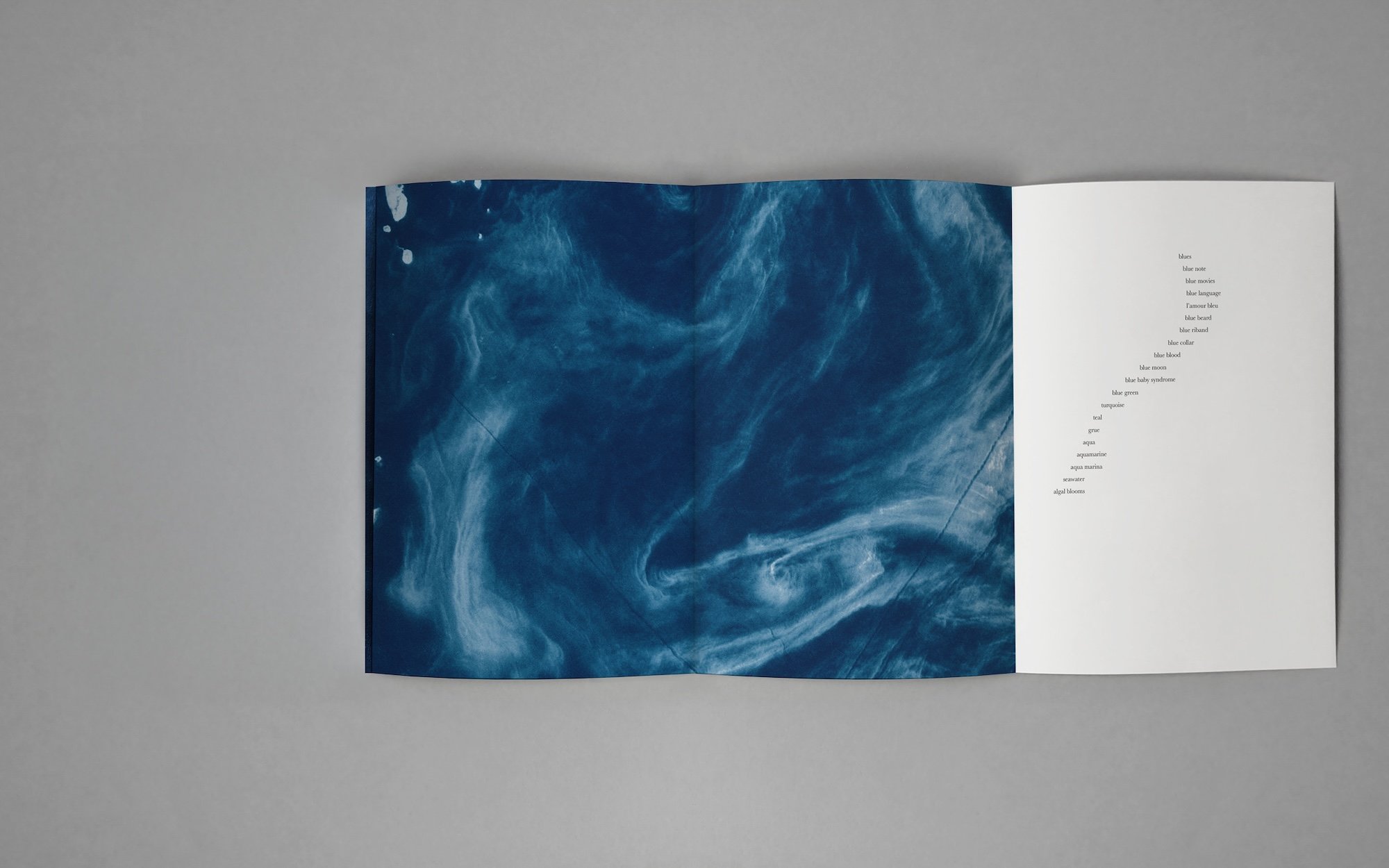

MS: I was curious to dissect this topic first in a very literal way, and then in an extremely metaphorical one—as well as exploring anything in between. I remember reading about the symbolism of the color blue and green, since algae is blue-green algae. There was a footnote about the Swiss biologist Adolf Portmann who was very much affiliated with Carl Jung. As the saying goes, one book opened another. This kind of research triggers my interest—the co-mingling of scientific and symbolic knowledge, which I feel ultimately are not separate though they might seem like it, especially in our culture. I was just following this invisible red thread. When I start working on something suddenly I’m on alert and then things begin to link to each other.

I also wanted to learn more about Baltic and Slavic culture, its mythology and cosmology. It was interesting to learn how much of that Slavic knowledge was destroyed during an enforced conversion to Christianity. In the Baltic countries, somehow they were able to dance the dance of letting this new religion in but still maintaining and preserving their own culture. Books by Lithuanian anthropologist Marija Gimbutas really informed the work. At one point in the book there is a list of the names of the Baltic Sea in the language of every country that borders it. In Germany it’s called Ostsee because it’s east of the country. But in another country it might be north. There is no fixed point.

SW: Woven into dialogue with the symbolic and mythological reflections on the Baltic is the scientific research you engaged with, building a bigger web that shifts between different forms of knowledge. That scientific information becomes more storied and unfixed.

MS: Some of these scientific papers even say that they don’t know. In the book there’s a fragment that says “everything is everywhere, little is known”—and that is actually a sentence from a scientific paper. Not philosophy, not Jung, not poetry, but a report that is talking about cyanobacteria. There is no consensus on how to classify it; according to its morphology and behavior it could belong to multiple categories. This exposes the idea that it’s not actually so easy to place a living organism in a box and expect it to stay there.

SW: Reading the book feels very watery as we flow through so many different efforts to contain this issue in text. Did working on the project change your experience of the sea and your relationship to it?

MS: I now live in a desert very far from the sea. If anything, any time I go to Poland, it’s really important for me to go and spend some time with the sea—as a way to honor working and connecting with it.

SW: That’s a good marker for how working on or even encountering a project like this can have tangible effects in your behavior towards the environment.

MS: In general it’s about paying attention. This work is my way of paying attention to different things—because actually everything was already there and available. I felt it was also important that I wasn’t just sitting somewhere in the distance, reporting. This is why I stopped working as a journalist; I became so disillusioned with this idea that I’m sitting at my desk in London, writing about Design Miami. I’ve never even been there at that point, and I’m writing a review. It’s nonsense! I didn’t want to perpetuate that. That’s why I decided to spend some time with the sea and see what comes out of it.