As a teenager, Mari Katayama was big into Myspace. “I had more friends online than I did in real life,” says the Japanese artist. This was the early noughties, in the peak of the Myspace blogging boom, and the platform played a huge part in Katayama’s development as an artist. It was where she posted pictures of her drawings, met future collaborators, and eventually, shared her very first self portraits.

Myspace was central to the photographer’s life, but part of the reason she devoted so much time to it was to escape reality. “When I got to high school, my goal was to not make a single friend,” she says. Katayama was born with congenital tibial hemimelia, and at nine years old opted to have her legs amputated. “I cut off both legs because I wanted to walk normally like everyone else, but when the prosthetics arrived, I felt like I had robot legs,” she says. “When I got to high school, the uniform required me to wear a skirt. I thought, if I couldn’t hide my legs anymore, I would just avoid people altogether.”

Katayama’s stepfather worked in IT, and bought her a PC when she was 14. By 15, she had learned how to code her own Myspace page. “Online, no one knew I had prosthetics. They were just looking at my art and judging me through that,” she says. At the beginning, photography was a tool to record and archive her work: intricately embroidered objects decorated with seashells, crystals and collaged images.

As she gained a following, photographers started to reach out asking to take portraits of her. She agreed, so long as they photographed her with her art. “But afterwards, I realized that it was me in the pictures, and those were my objects that I had made—but the final image belonged to the photographer. My body had become their work,” she says. “I was being photographed because they thought my body was an interesting subject, and if I didn’t take my own self-portraits that dynamic would never go away.”

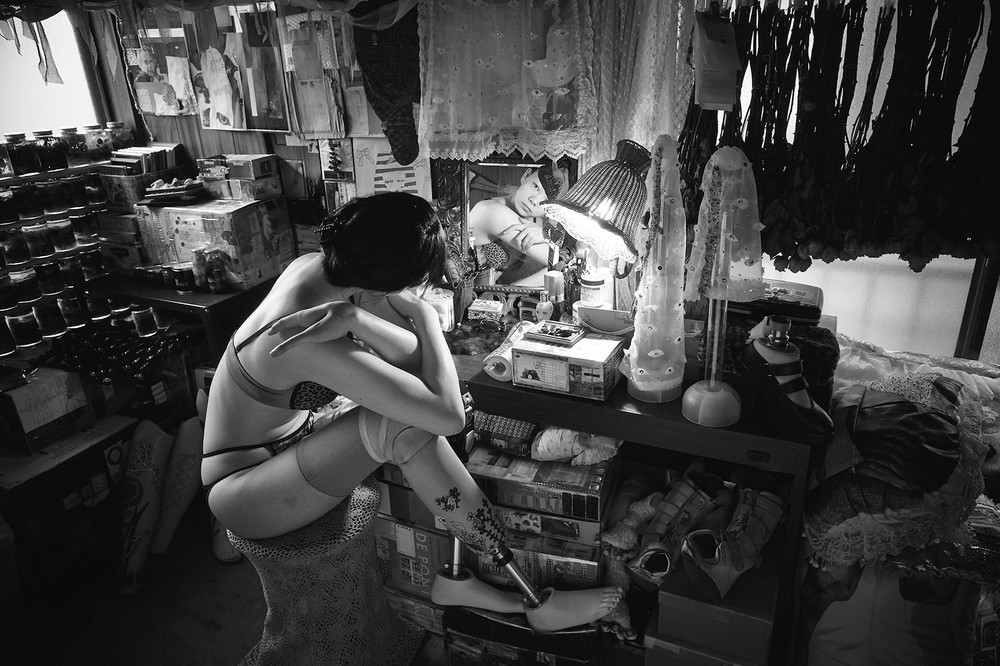

Now, Katayama is known globally for her dazzling self-portraits, her body surrounded by various objects she has crafted: prosthetics adorned with painted tattoos, lifesize mannequins embroidered with lace and sequins, toys and seashells strewn with glistening fairy lights. Her work has been exhibited in world’s top art institutions, including Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Mori Art Museum, and the 58th Venice Biennale. This month, she will exhibit as part of a group show at Foto Arsenal Vienna opening on the 31st of August, and in October she will show work at London’s Tate Modern as part of a display of its permanent collection.

The photographer’s work defies labels. Katayama’s body is a consistent subject in her work, and while she acknowledges her own presence as a person with a disability, she is clear that it is not the defining theme of her art. “People who see my work tell me I’m so strong, that I have so much courage in showing myself ‘as I am’, that I’ve created a new concept of beauty—usually using buzzwords like ‘body positivity,’” she says. “I’m not making my work with that intention at all. My work is not about disability rights, it’s about the human condition. I’m making work around themes that affect anyone who is human, not just people with disabilities.”

This isn’t to say her work hasn’t had an activist edge. Back in her early 20s Katayama was performing at a bar, and a drunk customer told her “a woman is no longer a woman when not wearing high heels.” In response, the artist collaborated with Italian fashion brand Sergio Rossi to create a pair of heels for her prosthetic legs. The project is not just about Katayma’s own experience—it’s about women, societal expectations, and freedom of choice.

Equally, her self-portraiture is not about reclaiming her body or healing past wounds either. “If anything, making this work hurts me,” she says. “I don’t know if anyone wants to face themselves in this way. It’s like looking in the mirror and seeing all the pores of your skin.” For Katayama, it’s not so much that she chose to photograph her body, but rather that her ideas require it. “My self-esteem is in the minus points—I don’t think anyone who hates themselves so much should take self-portraits,” she laughs. “I don’t take pictures because I like myself or I want to face up to myself… What I want to do is make art, and self-portraiture is a medium within that. When I conceptualize a project, and I think about what it’s going to look like, my body is part of that, so I include it.”

A great deal of time and precision goes into making each one of Katayama’s portraits. She spends at least a week setting up the installation and refining the composition, while the actual shoot only takes an hour or two. When she was working with a digital camera, Katayama would take hundreds of photos in one session, but in recent years she has pivoted to film. “I never really cared about the distinction between film and digital,” she says, explaining that when she first started, she intensively studied the technical side of photography. She found herself equally frustrated and disillusioned by the photography industry, specifically the “old men” who seemed to be more interested in camera models and printers, than the ideas behind a photograph.

Digital photography was quick, efficient, and served its purpose, but this all changed six years ago, when she gave birth to her daughter. “A child’s face is totally different 30 seconds after they’re born, to five minutes after, and even the next morning. It changes almost by the hour,” she says. “But I didn’t just want to record her face, I wanted to preserve that moment in time… I realized the only way to truly capture that was to use light, air, and physical film, and conjure that moment through a chemical reaction.” It was this shift in how she documented her own personal life that gradually transformed how she makes her artwork too.

This move into a more tactile medium makes sense considering craft is such a big part of her practice. In her studio in Gunma, about two hours outside of Tokyo, Katayama stores large containers full of props, beads, and fabrics. Her approach is largely influenced by her family. “Everyone in my family is creative,” she says. Katayama’s mother, grandmother, and great grandmother all loved to sew. When she had her legs amputated, she had to wear huge boots in order to walk and couldn’t wear normal trousers. Her mother made special clothes for her—sometimes matching. Katayama’s grandfather was also a lover of art, and would drive them to their local art museum every weekend. There, she fell in love with Modigliani’s paintings, which were displayed in decorative metal frames. “That’s why I decorate my own frames with seashells and crystals,” she says. “We were poor, and we had no money, so making rather than buying has been ingrained in me from a young age.”

Katayama is now in her mid-30s, and has already produced an impressive lineage of work. She speaks about her practice with intention and eloquence, highly conscious of the purpose of her work and who it is for. “That’s something I’ve been thinking about a lot lately,” she says. “I feel like I’m making art for art… I love beautiful things, and I know art isn’t just about that, but if I’m going to make art, I want to make it beautiful.”

The medium of photography is well-suited to this pursuit; it allows her to be expressive both behind the lens and in front of it. “I’m very aware that it’s only been 10, 20 years, but my photographic expression has matured so much in terms of experience and knowledge. If I hone my skills more and more, like sharpening a knife, maybe I’ll reach that epitome of beauty that I’m searching for.”