When you hear the word Switzerland, what do you picture? The Matterhorn, perhaps? Heidi and alpenhorns? Cuckoo clocks? On that note, Harry Lime in The Third Man got it wrong. The cuckoo clock is a German invention. So then Rolexes and chocolate and cheese? Trains that run on time and business suits that move money around? Switzerland is neutral, staid, some might even say boring. But is it really? Perhaps we are just not looking closely enough.

For the Turkish photographer Pelin Guven, moving from Asia to Switzerland brought about a whole new way of looking. In Absence, she invites the viewer to take a deeper look at moments that dance between hiding and revealing themselves. Through bold shadows, shots of color, and an eye for detail, she captures a world where glimmers of humor and an air of mystery catch the eye.

Living abroad in a variety of different locations has led Guven to record her life in the new environments she finds herself in. “Moving through unfamiliar places with my camera helped me pay closer attention to light, people, gestures, and the small atmospheric details I might have missed otherwise,” she notes. “My background in psychology has sharpened my sensitivity to how we read the world—how a subtle gesture, a shift in light, or the smallest cue can completely alter what we perceive.”

“This work grows out of the quietness and privacy of Switzerland, and the natural distance built into daily life here. After many years living in Asian cities, where people live very close to one another, where the streets are full from morning to night, and where daily life naturally flows into public space, moving to Switzerland presented a complete contrast. Here, cities are small and quiet, and people prefer more distance. They are reserved, private, and interactions often stay minimal,” Given observes. “This difference didn’t just change my environment; it changed how I photograph.”

When life on the street is more restrained, one has to adjust. There are photographs waiting to happen but the looking may take longer. Switzerland gave us the Helvetica font and the Swiss army knife, clarity and efficiency. It also gave rise to some of the most joyous, anarchic conceptual artwork of the last few decades. From Fischli/Weiss’s The Way Things Go—a video made with a confounding Rube Goldberg machine— to Pipilotti Rist’s Beyonce-influencing exhilarating rampage Ever Is Over All, to the playful ephemerality of Roman Signer’s action oriented performances, creativity sprouts in response to the order and conformity of Swiss life. It may not always yell from the rooftop, but it bubbles up under the surface—with a wink and a laugh, or a flash of surprise.

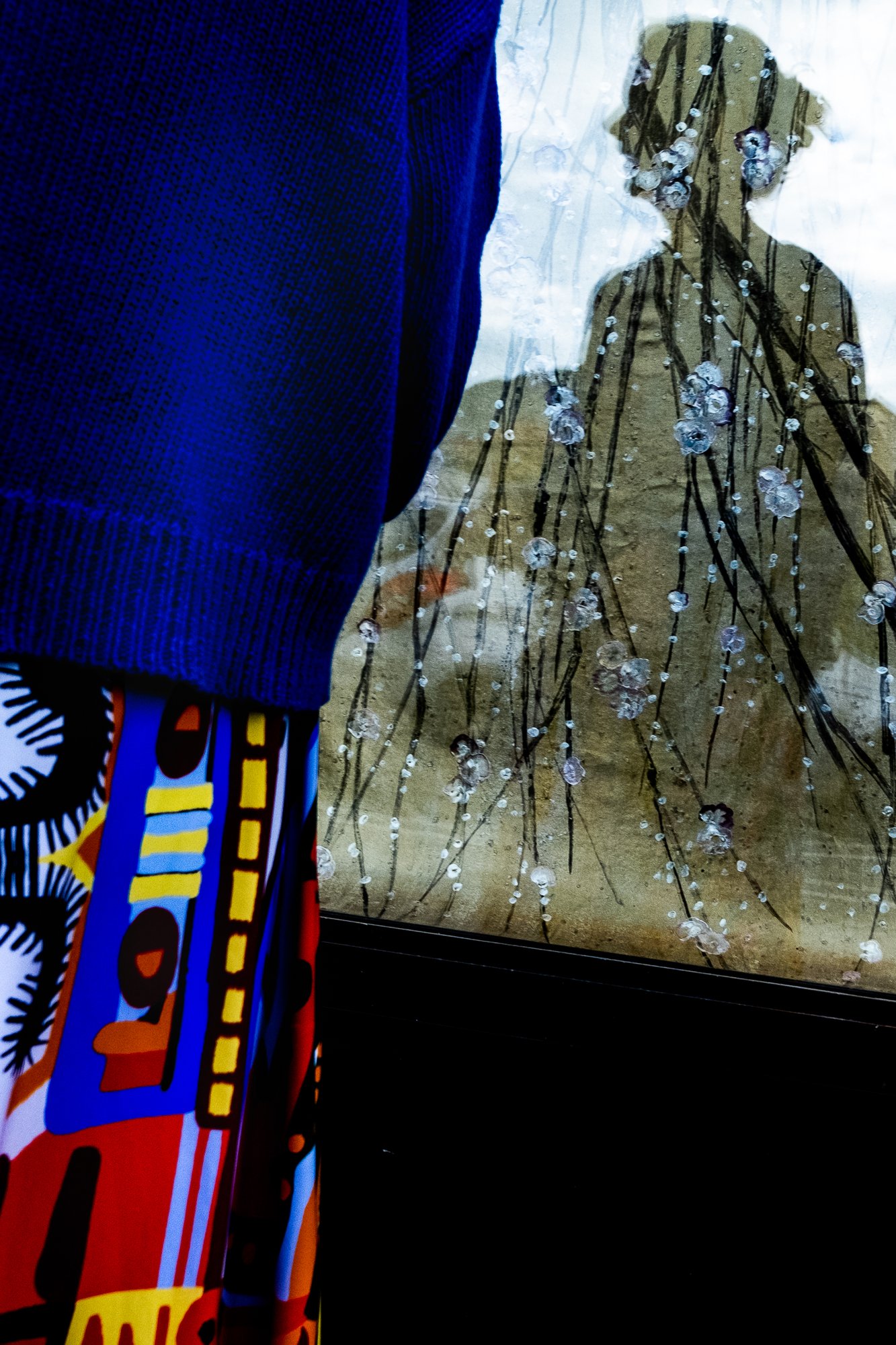

“In Switzerland, I have to look for much finer details: a small gesture, a brief expression, a pop of color, or the way the light and shadow briefly shape a moment before it disappears,” Guven explains. In her images, moments of dramatic color or patterns emerge from the quiet streets. A figure with a shock of flame-colored hair laconically observes a view, a woman in cerulean cuts through the deepest of shadow. “I’ve always been a quiet observer, drawn to the unnoticed moments that hold a certain tension or beauty.”

It is this tension that catches the eye. Guven’s use of shadow in her images is striking. At times more than two-thirds of a photograph recedes into inky blacks. This boldness of negative space is the perfect contrast to moments of illumination. A woman’s eyes track the viewer from behind wire framed glasses, flipping the true subject of the image on its head. In another, a slice of watermelon glows like a beacon, each bite mark perfectly defined, one can imagine the taste of it. “I am drawn to what is not fully visible. Light, color, and shadow interest me not only for what they reveal, but also for what they leave out. Often what sits just outside the frame, or what has just happened or is about to happen, carries more tension than what is directly seen,” she observes.

“We see people in the street, but we do not know their inner world. Appearance suggests one thing, while the truth may be entirely different. This gap between what we assume and what we cannot know is what draws me in. The surprise, the unknown, the simple act of getting lost in a city and turning left or right purely on instinct is where I feel a sense of freedom,” Guven explains. In walking the city with a new perspective, she’s captured a series of moments that break through the reserve of Swiss life, winking at the viewer, inviting them to help fill in the gap, and carry the story onward.