A defining moment in my life, as not only a writer but a reader, came early. Sitting with my mother, in her bedroom, we read Margaret Wise Brown’s seminal children’s book Goodnight Moon. In the story, a young rabbit says good night to just about everything. “Goodnight stars, goodnight air, goodnight noises everywhere,” he announces while tucked up in bed. My mother read, and I followed along until she turned towards me and said, “You read this page.” The words began to swim in front of me and the panic grew.

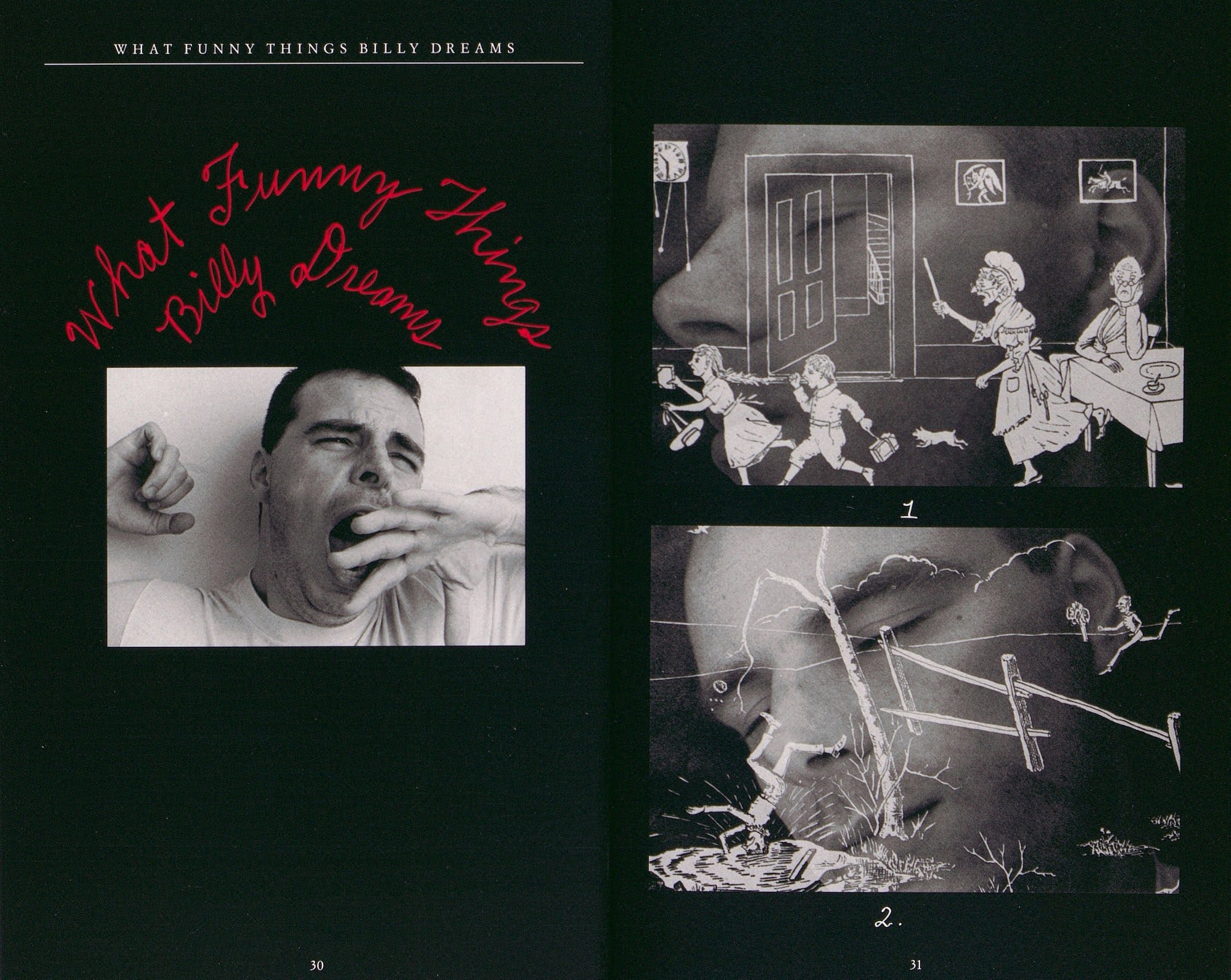

Rather than admit that I was struggling to read the words in front of me, I went rogue and started reading the images. “Goodnight clock” I tried. Met with no resistance, I was off and running. “Goodnight fire, goodnight lamp, bye bye phone, sleep tight curtains… sweet dreams… blanket?” One look from my mother and I knew the jig was up. There was no going back, so I threw the book down and dramatically declared, “I will never learn to read.”

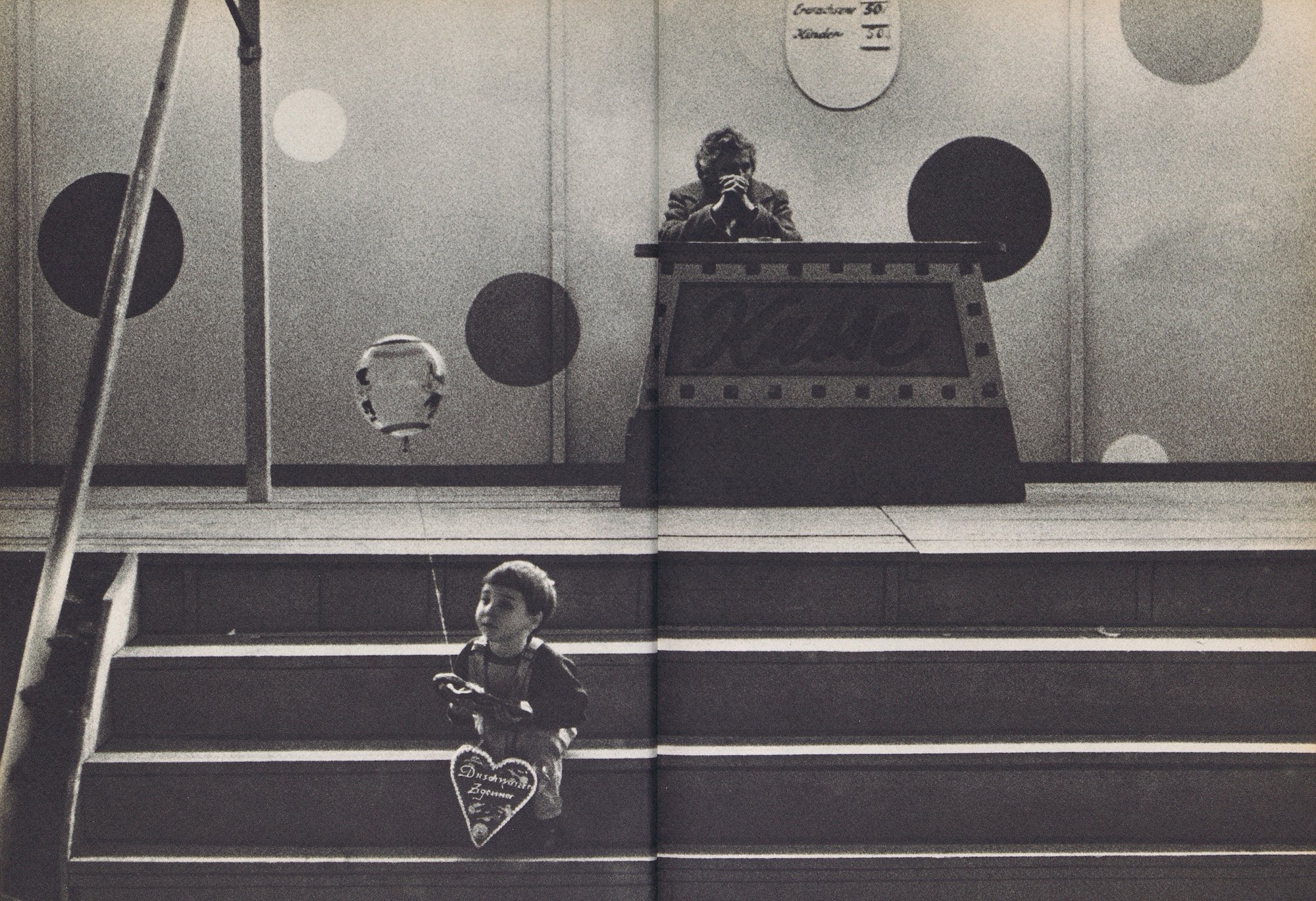

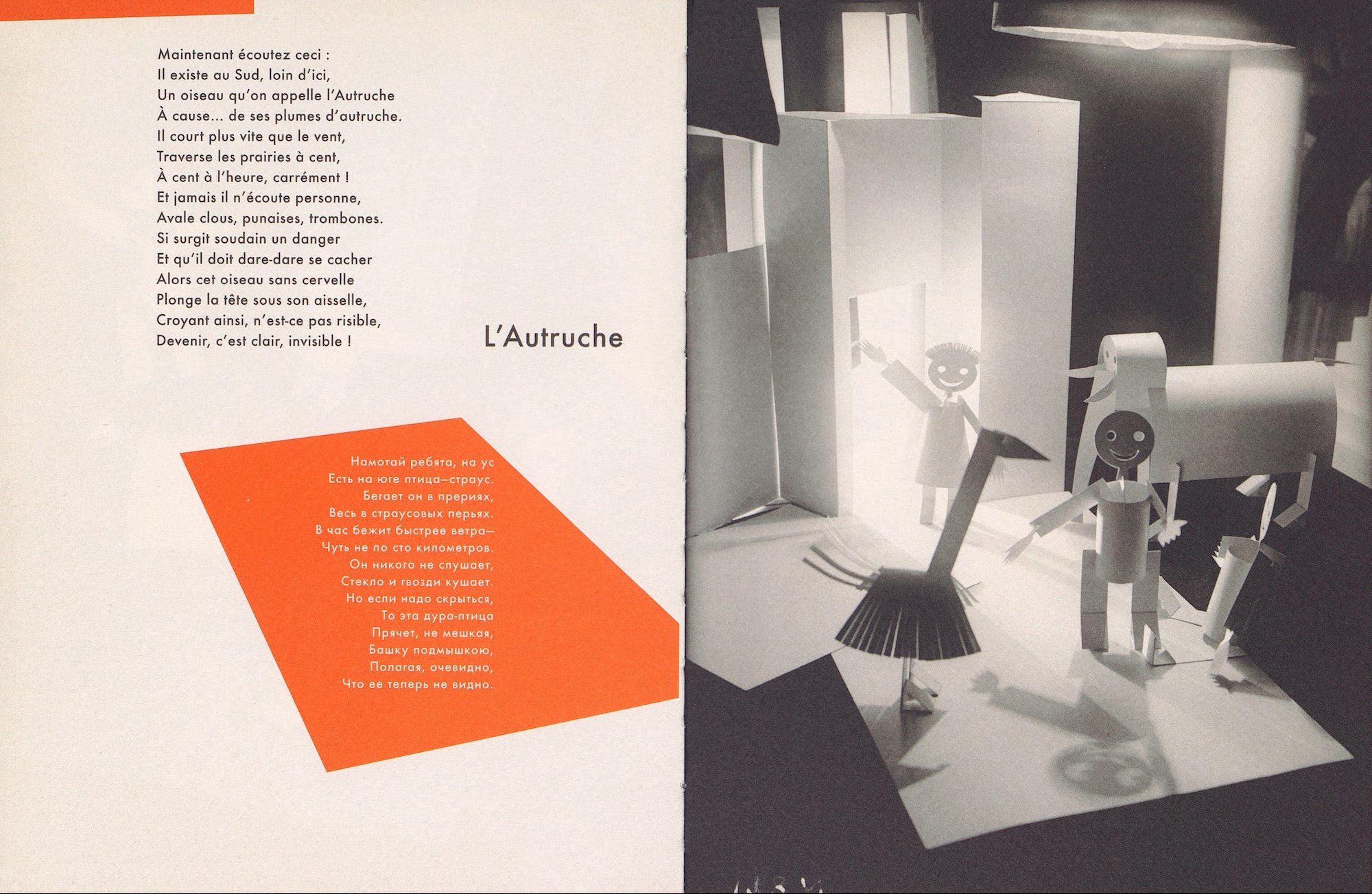

All this to say, it was an inauspicious start to a lifelong love affair with books. It would take me a while to master the art of reading words, but images? I was a pro and what a complete joy it was to look at them! In the pages of a book, images unfold into adventure, introducing children to the wonders of narrative. For many children, reading is first and foremost the deciphering of images on the way to storytelling. And so it is fitting that the traveling exhibition, L is for Look, currently on view at Lausanne’s Photo Elysée, begins the story of children’s photobooks with their role in the fields of pedagogy and education. In the 1930s, as mass market publishing gained steam, photography became the medium of choice for many early childhood educators.

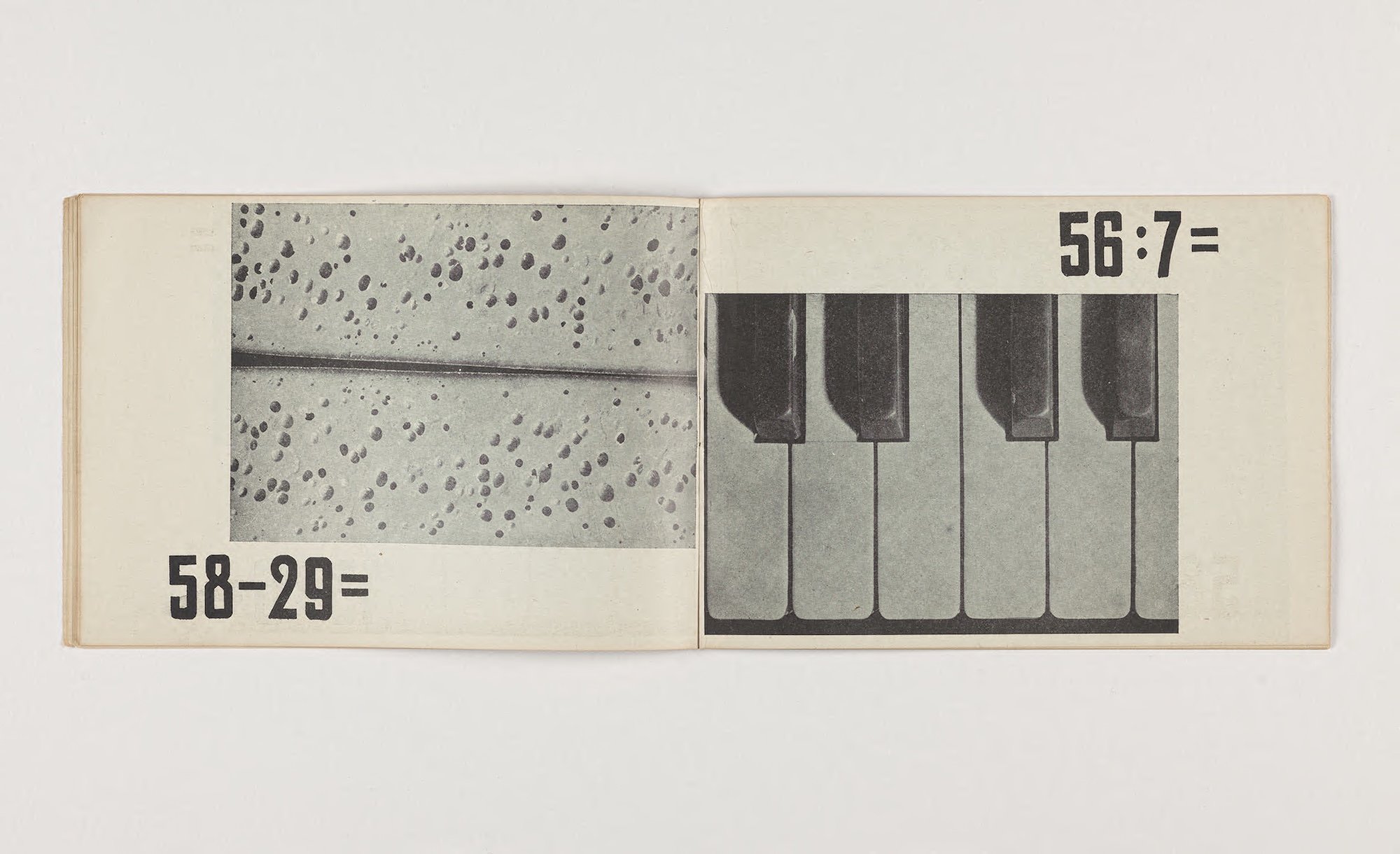

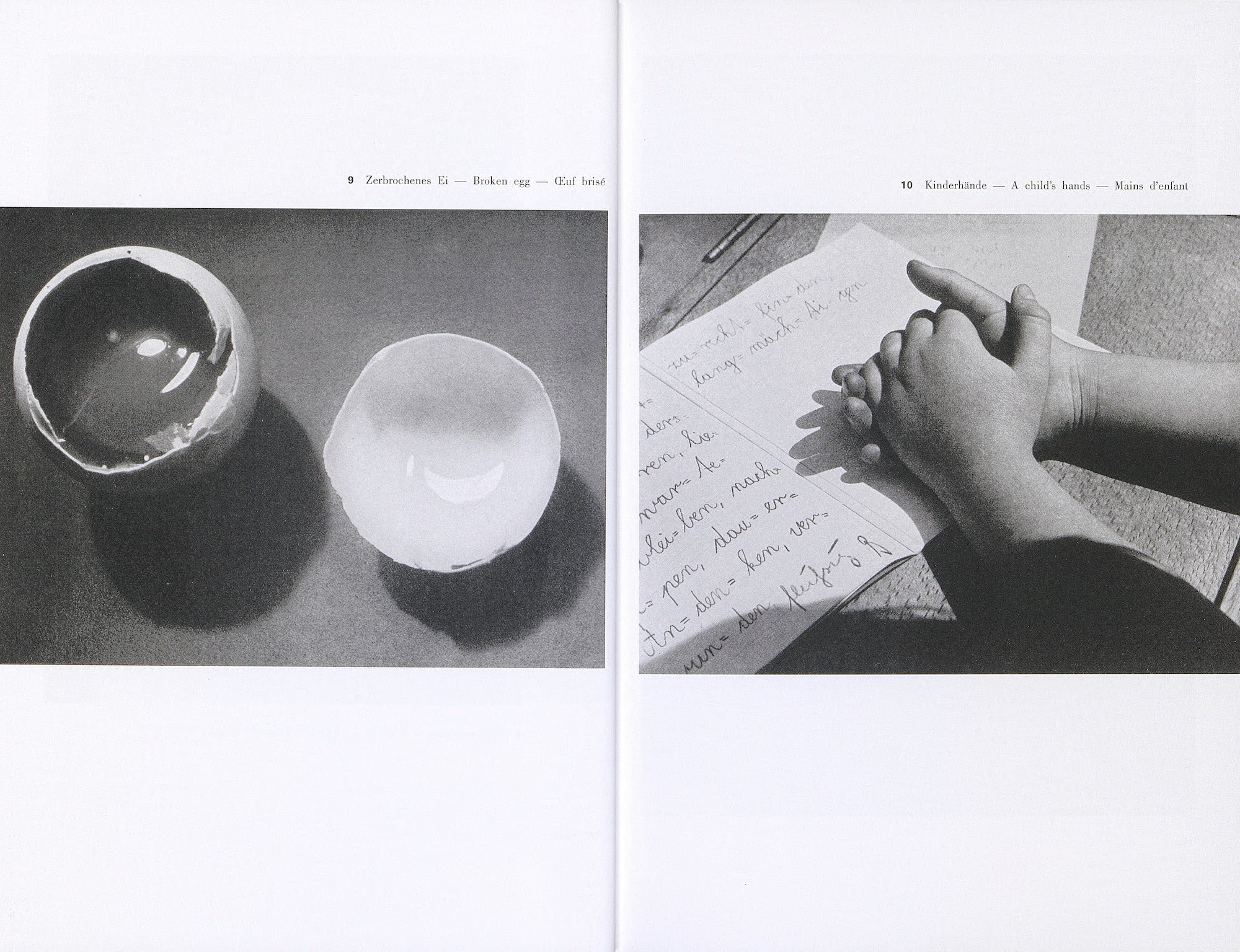

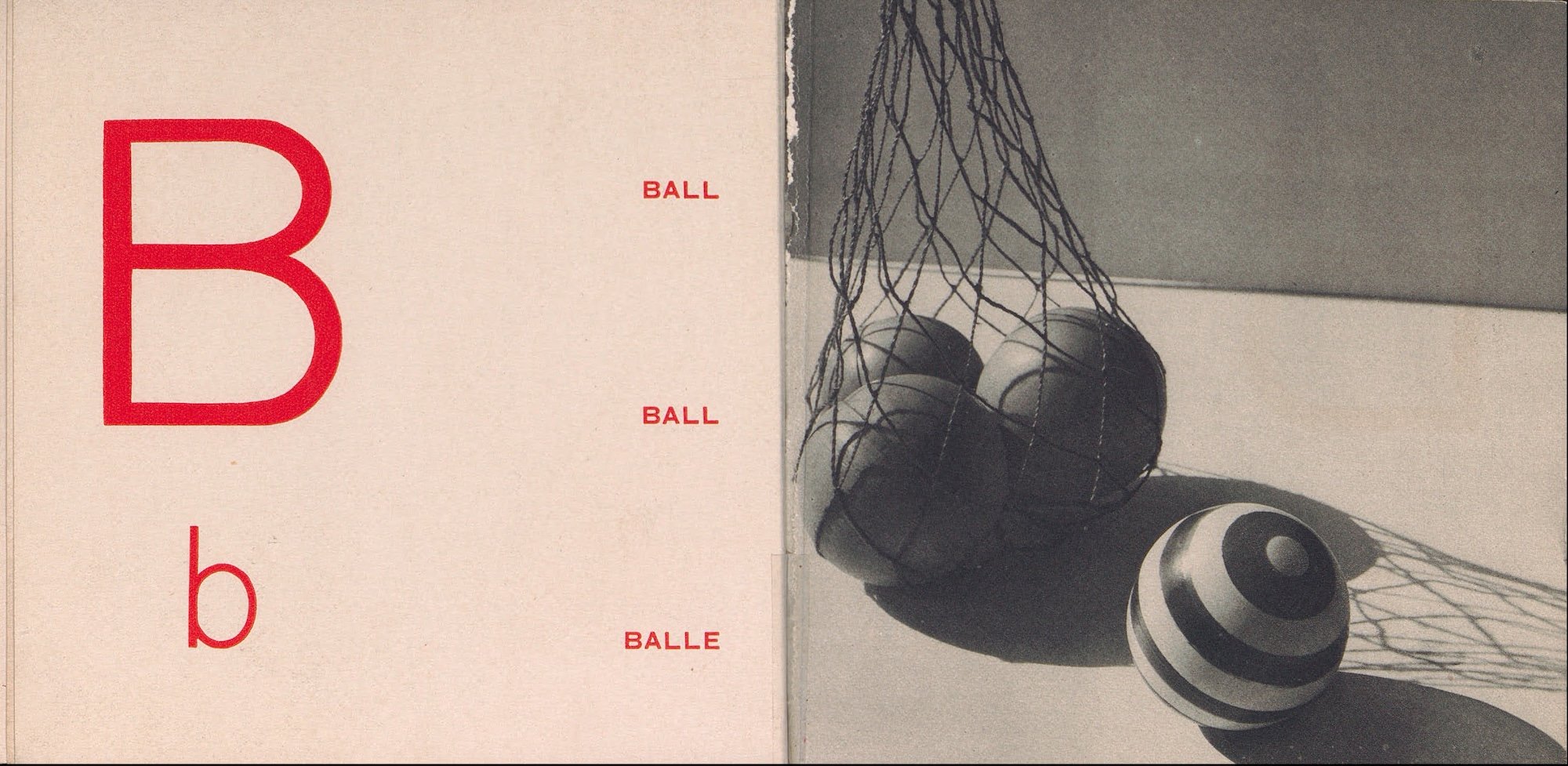

For Mary Steichen Martin, who created books with her father the renowned photographer Edward Steichen, photography, with its deep links to science and technology, was more fitting for early cognitive development. Illustration, she believed, “falsified reality.” Together, the Steichen family produced a book of black and white photographs, The First Picture Book: Everyday Images for Babies. The photographs are simple—scribbles on a sheet of paper, a plate of toast—yet captured with an artistic eye.

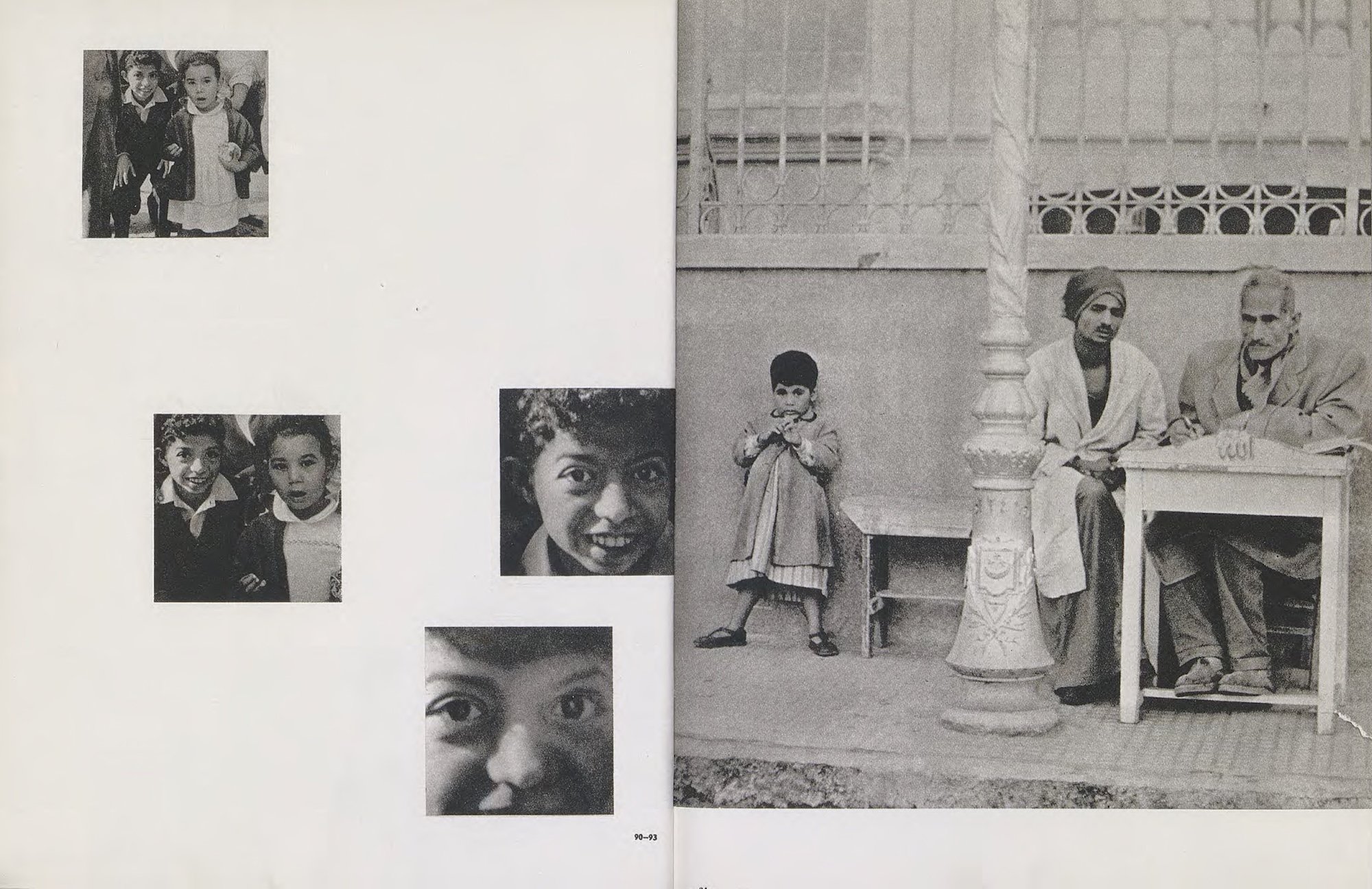

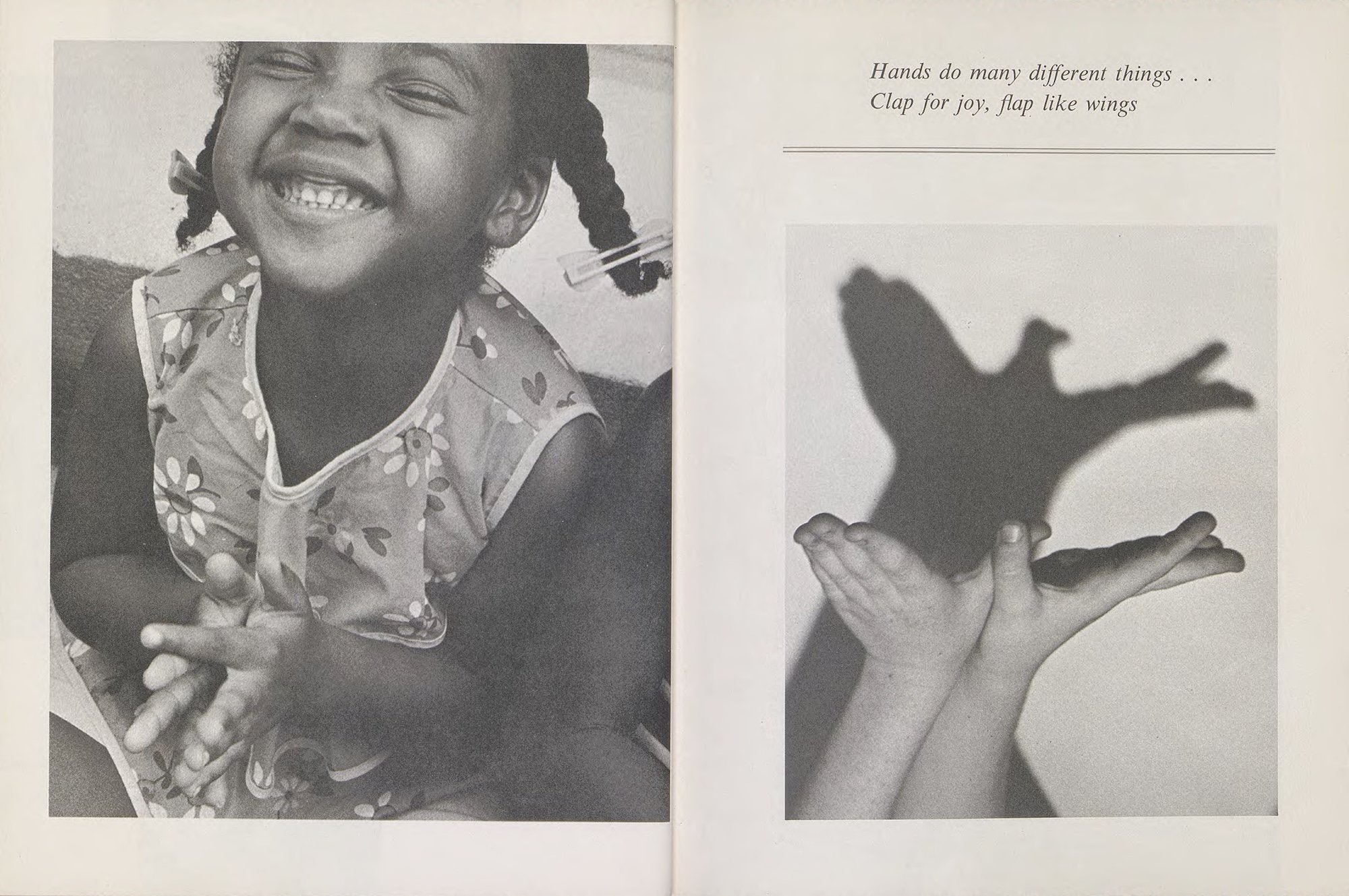

Seen alongside these images are Tana Hoban’s strikingly contemporary photographs. Hoban created over 100 books in her lifetime, many of which are still in use today. Combining photographs, illustrations, and bold graphic design, her books teach children to observe the world around them. Shifting between close-up details and intimate, candid shots, her images hum with energy, as if one can hear the voices and movement just outside the frame. Prints from The Wonder of Hands depict children’s gestures as they count and play.

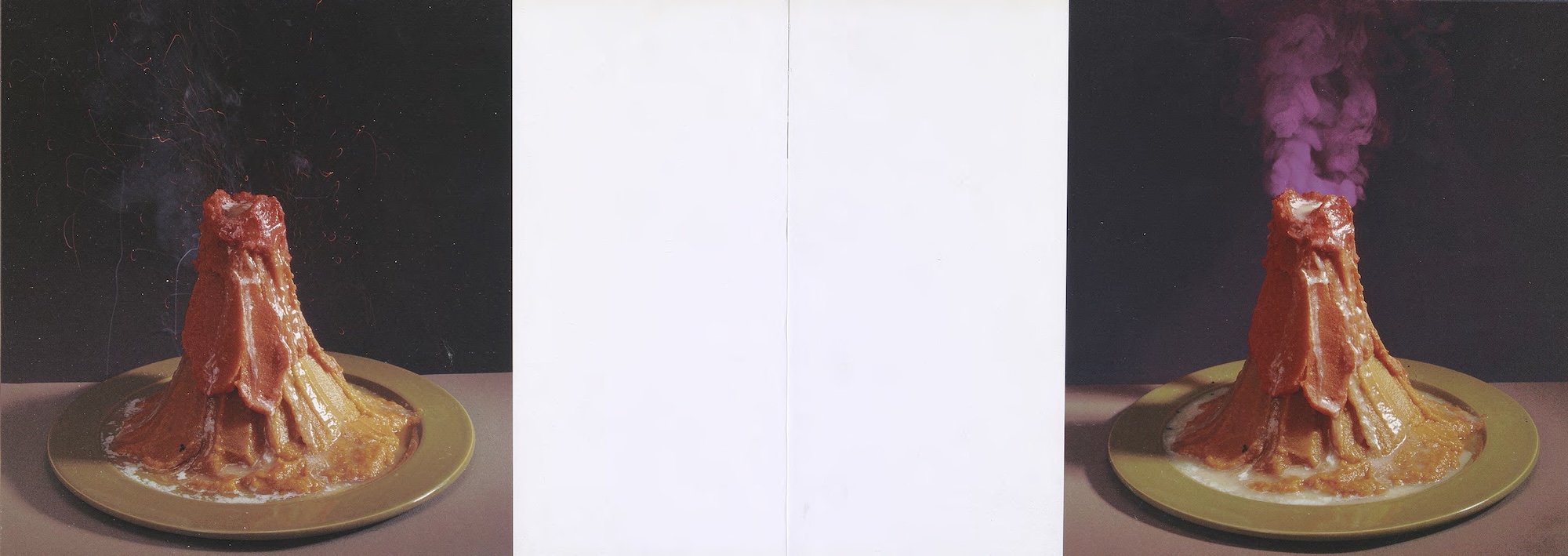

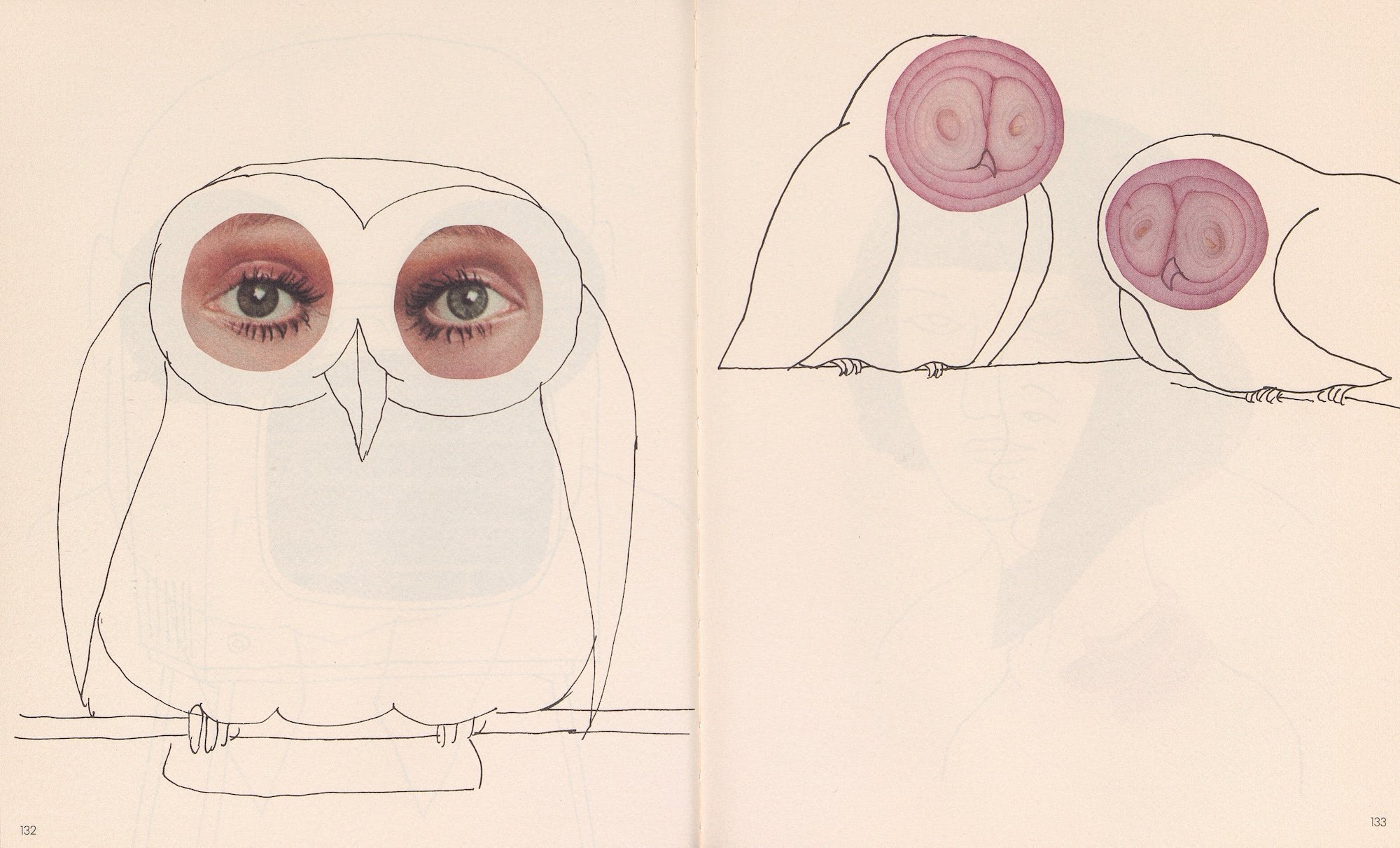

As the exhibition expands, it touches upon other themes to share the medium’s history and its connection to influential photographers and artists. Artist duo Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin, Annette Messager, and Emmanuel Sougez are but a few of those on view. The postwar photographer Shigeichi Nagano’s images illustrate Yoru no byōin (Night Hospital), to teach children about medical emergencies, while the surreal, satirical collages of Tomi Ungerer appear in Click Clack, or What is That?

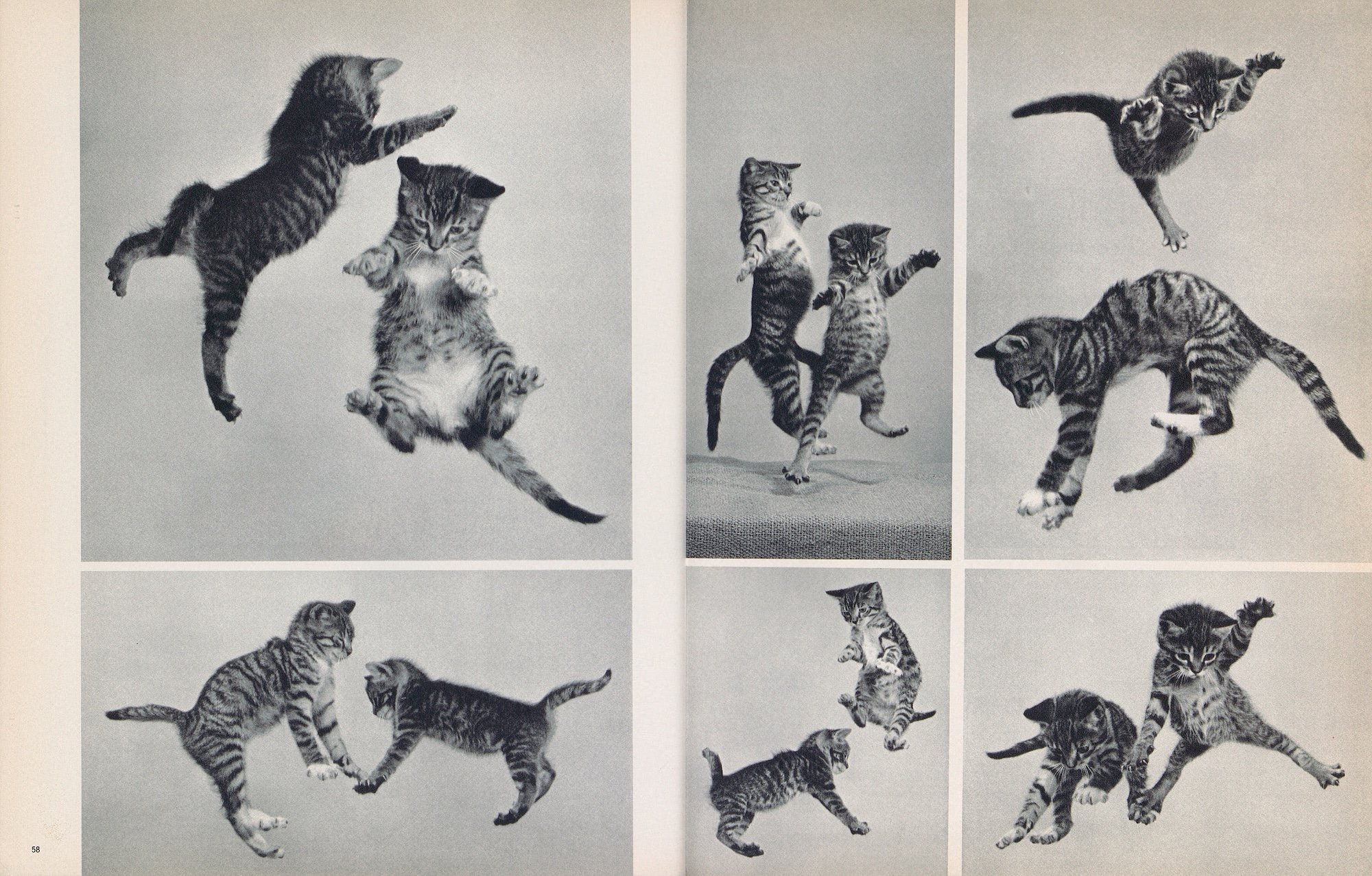

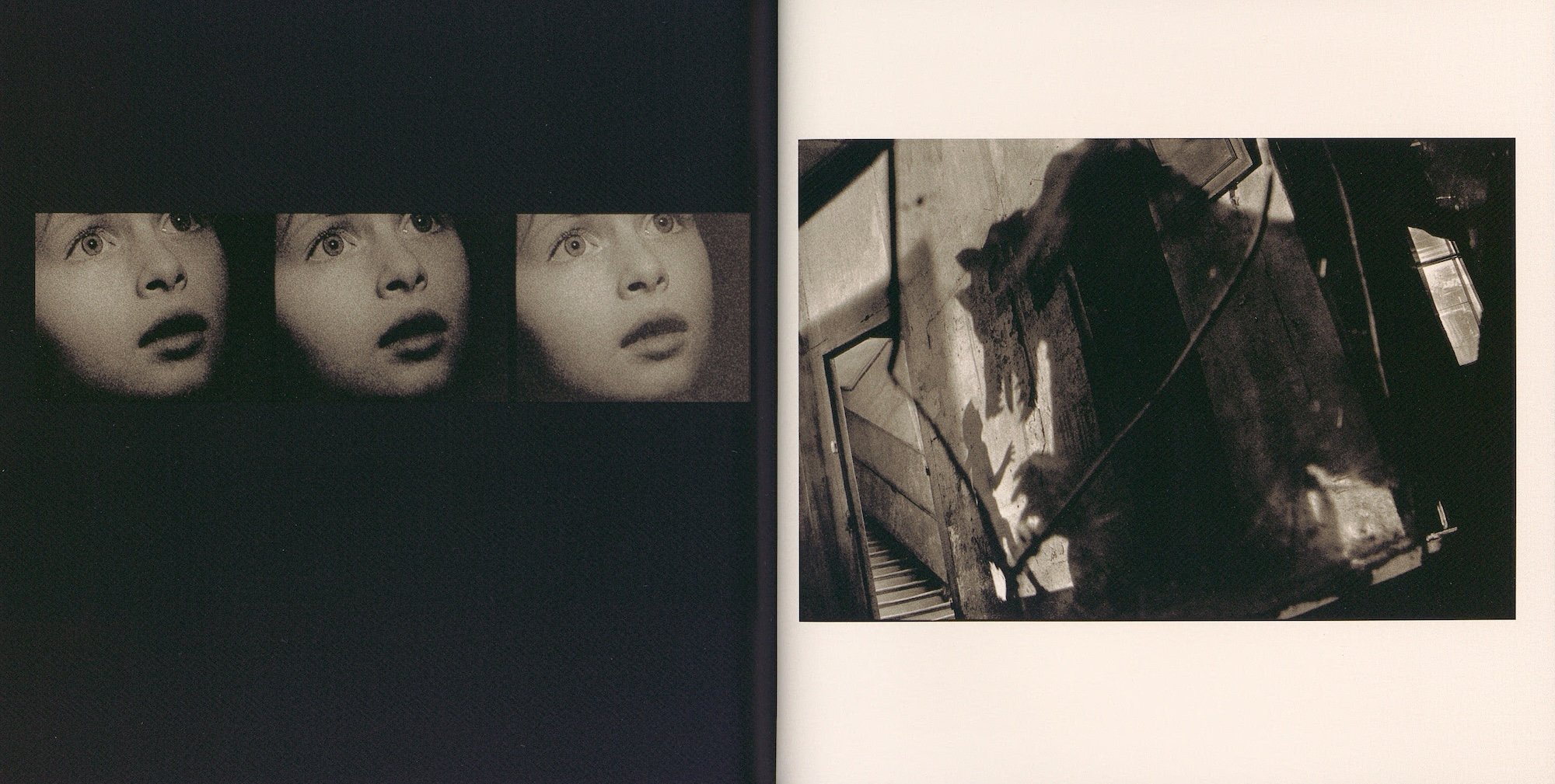

Further sections highlight the roles of fiction, graphic innovations, and interactivity. In the section on animals, the work of the Hungarian photographer Camilla ‘Ylla’ Koffler shines. Considered one of the greatest photographers of animals, her portraits brim with personality and action. Dogs, those faithful friends, appear in the guise of William Wegman’s famous Weimaraners and the Japanese photographer Eikō Hosoe’s Taka-chan and me, following the adventures of a young girl and her dog in luminous black and white images. In My Dog Rinty, Ellen Tarry, a journalist and figure of the Harlem Renaissance, worked with Marie Hall Ets and Alexander Alland to tell the story of a young boy and his mischievous dog. In all of these works, children are introduced to far more than just imagery. Empathy, diversity, and story arcs are presented with care and detail.

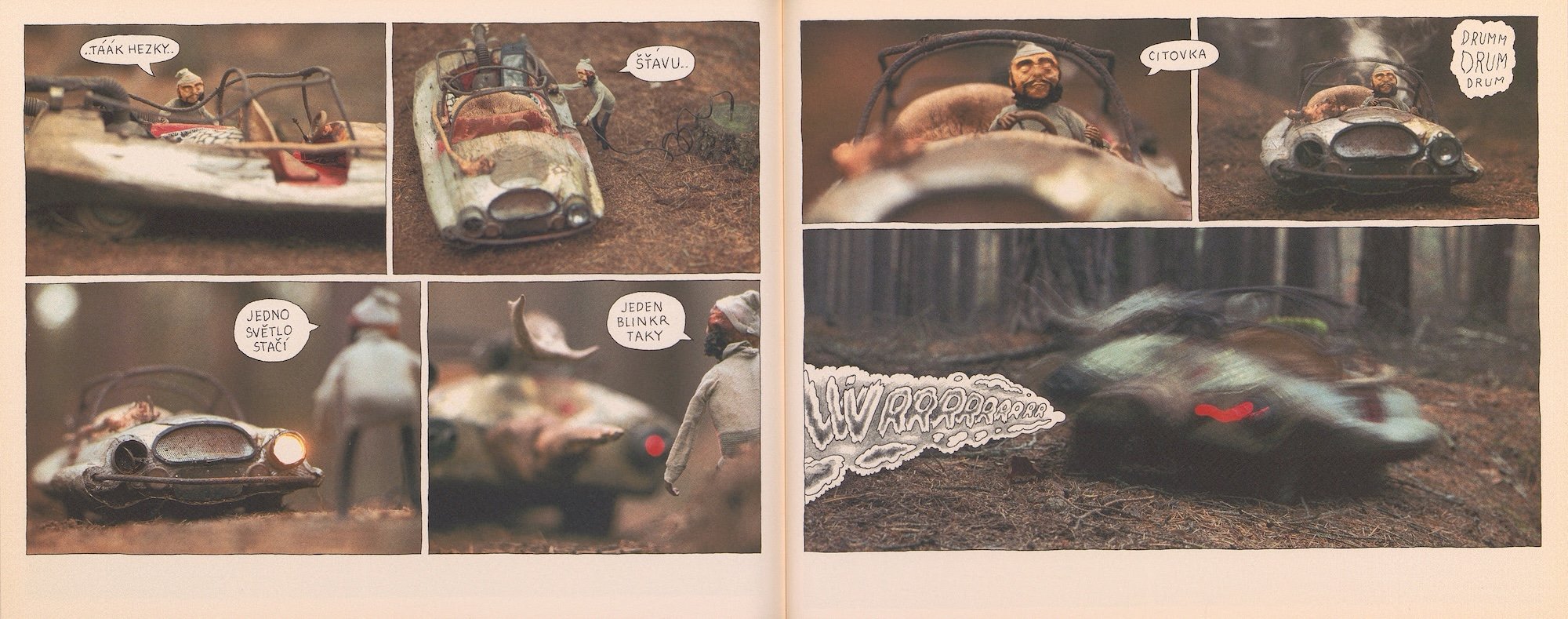

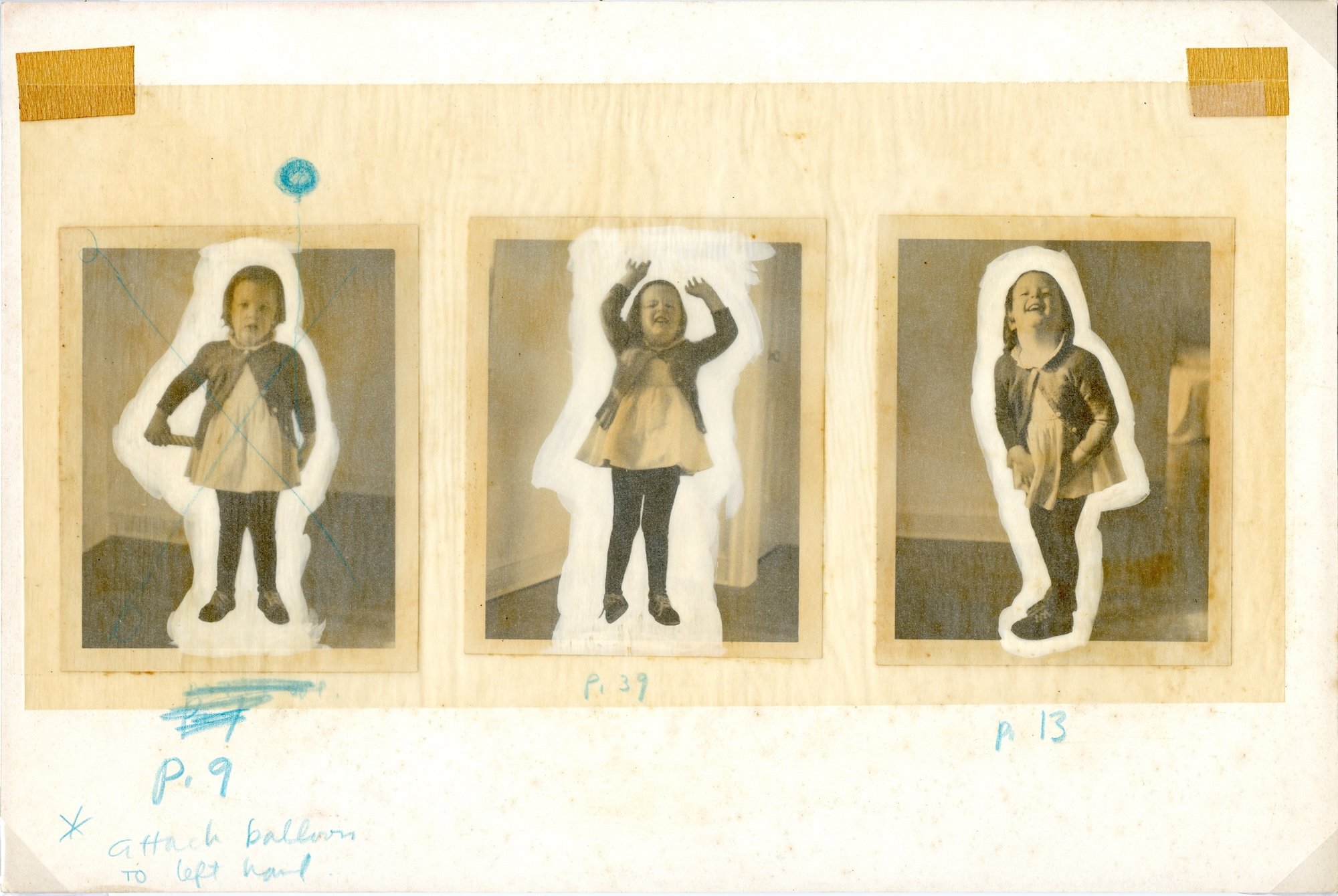

The sophistication and creativity of the books on view is striking. A picture is worth a thousand words, and L is for Look plays beautifully with this tried and true cliché, with images that open up a world of discovery for the young reader. It is too easy—or perhaps lazy—to overlook the fact that children are by far the most imaginative amongst us. The works here never condescend or take their audience for granted. Instead, they take on the task like a gift, presenting the joy and seriousness with which these works were made. The curators present the background of individual projects and artists, with objects and studio images to illustrate. We see the actual puppet and climbing gear from The Tales of Amadou, an Alpine mountaineer, alongside an image of the Swiss photographer Suzie Pilet with her camera, preparing to capture Amadou’s ascent in the great outdoors.

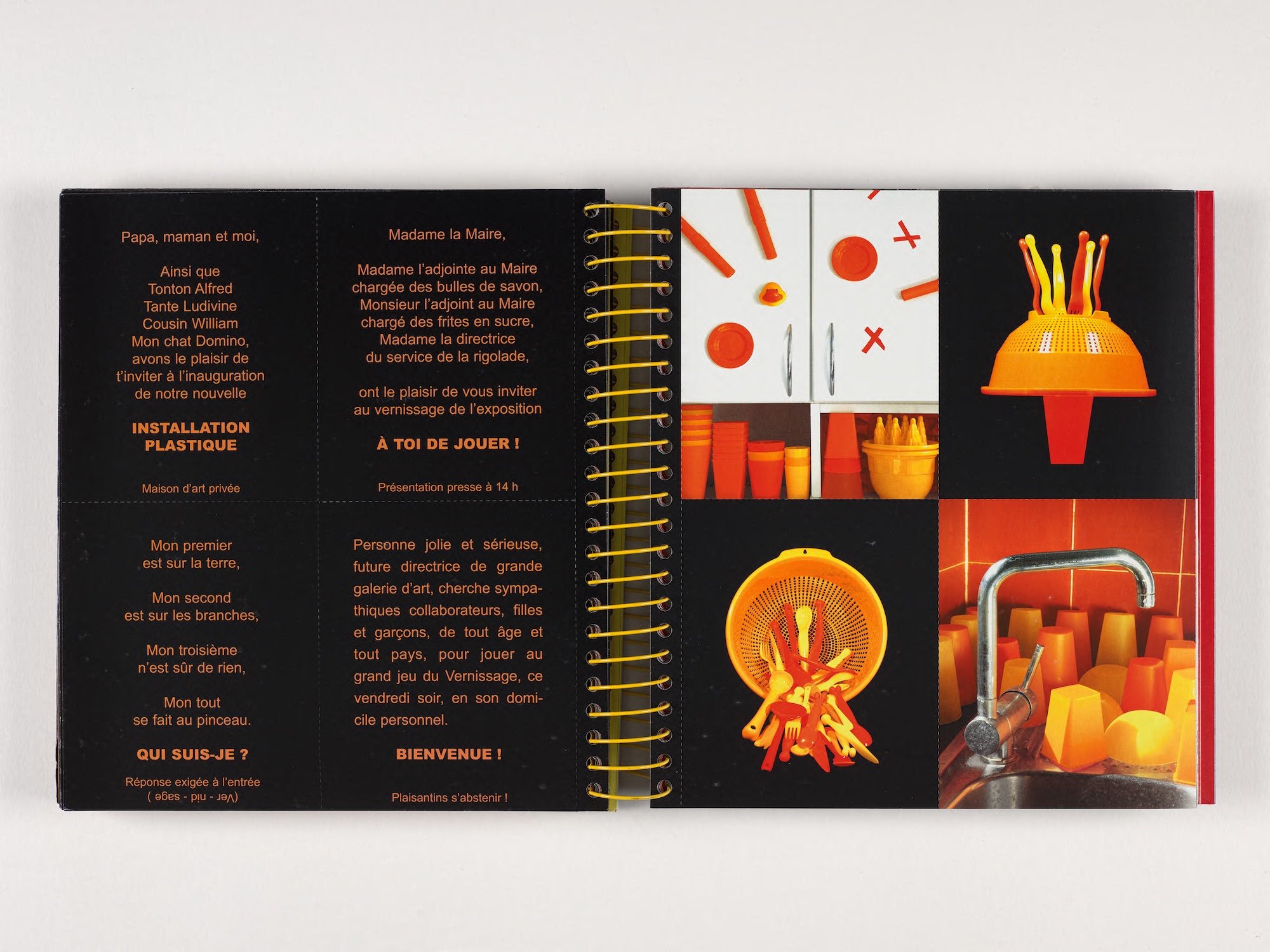

Within the walls of the exhibition, visitors themselves are encouraged to play and explore with books to pick up and peruse as well as the prints on the walls. At times, some of the photographs, encased in plastic holders, pale in comparison to the books themselves. The role of touch is important to these works. Throughout the exhibition, stations have been set up for hands-on interaction. Upon first glance, one might take this as a chance to occupy children, but for any viewer, it brings the creativity and fun of the work to life illustrating how books are designed to speak to both children and parents.

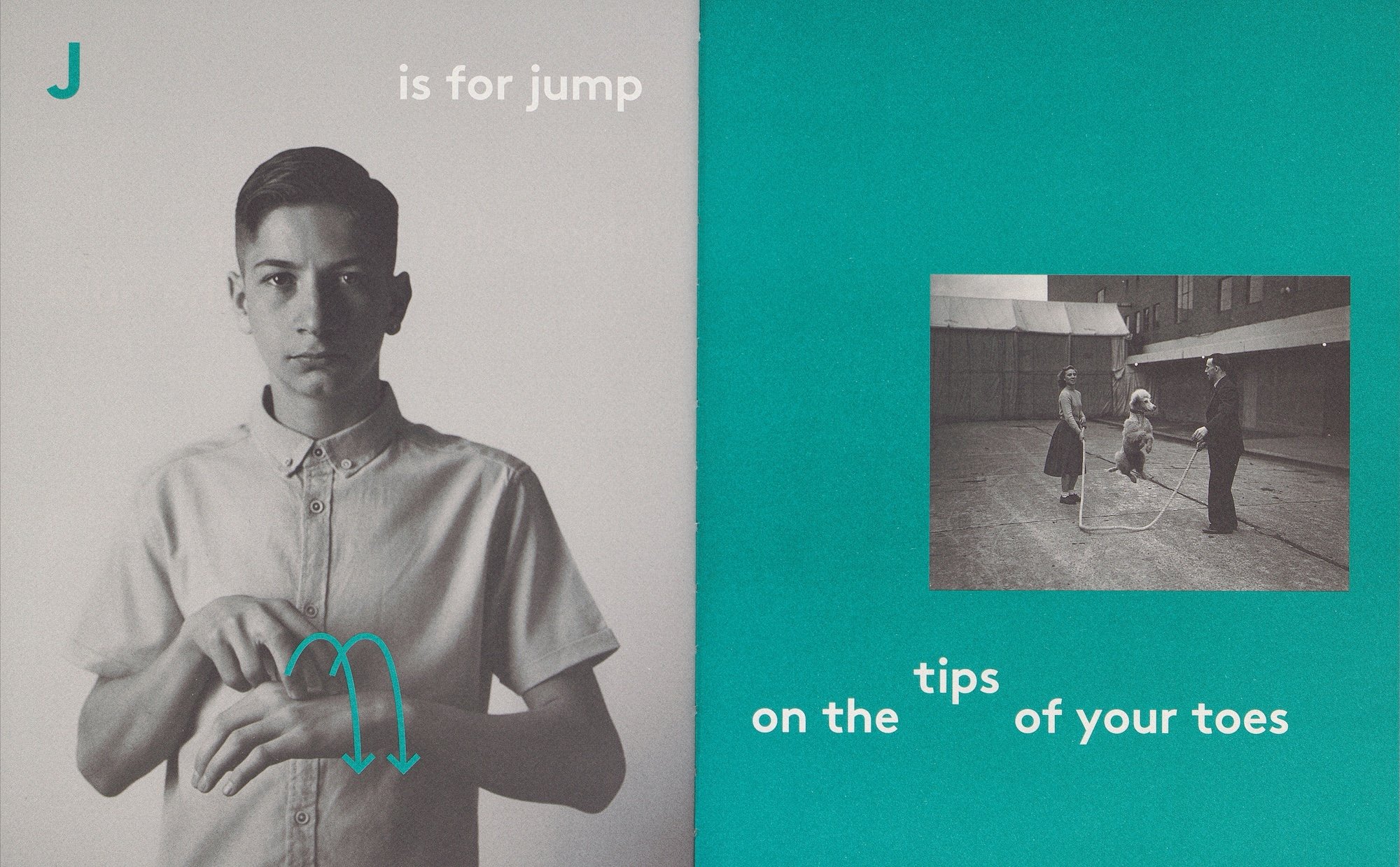

In ABC of Ecology, a project dating from the 1970s, by Donald Crews and Harry Milgrom, the authors use the form of an alphabet book to speak about the environment. “J is for jet plane,” announces one page. “Jet planes fly in the atmosphere. Jet plane engines burn liquid fuel,” the text reads, before asking the reader what they see in a stark image of a jet trailing exhaust. Often enough, these children’s books are far ahead of the curve in addressing real world issues—which they do so with the strength of clear, concise language. In a spread from Ann McGovern’s Black is Beautiful from 1969, children photographed from above produce long, stretched-out shadows on a playground. “Sunlight and shade—look back; The color of everyone’s shadow is black,” reads the accompanying text.

The breadth and variety of the books on view is a delight, though I found myself wishing for the inclusion of a handful more, young contemporary creators and publishers. There is a growing scene of artists making books not only with children in mind but also as collaborators. As the exhibition drew to a close, I thought back to recent projects I had seen at book fairs or come across online: the books of Citation Needed, an intergenerational publishing initiative that leads workshops for children or Childish Books, a platform creating and celebrating projects which “could be enjoyed by a ‘child audience,’ however defined” and the work of Some Other Books, integrating parenting with bookmaking and hosting zine caves at fairs. But perhaps that is part of a retrospective—to make the viewer look for more, figure out what is missing and search out how to fill the gaps. To continue the story as we walk out the door.

In a world of screens and short-form content, where videos pour forth in 30-second waves, a book can feel both solid and radical. L is for Look feels like a call ringing out, championing the age-old desire to flip a page, to read along, and ultimately to build a narrative of imagination for oneself. Perhaps the call is to heed the words of photographer Tana Hoban, who, when asked about photographing, told the Children’s Literature Review, “Look! There are shapes here and everywhere, things to count, colors to see, and always, surprises.”

Editor’s note: L is for Look is on view at Photo Elysée until February 1, 2026. It next travels to the Museum Folkwang in Essen from February 27, 2026 – June 7, 2026 and on to Arles, London, Luxembourg, and Vienna before finishing in Lille in 2028.