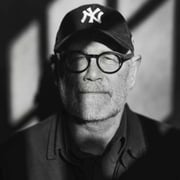

Roy Kahmann is the Founder and Director of the Hungry Eye Group, an international photography platform uniting galleries, publications, talent books, and curated fairs. Trained as a designer, he evolved into a collector, curator, publisher, and entrepreneur who has championed Dutch and European photography on the global stage. Through ventures including the Hungry Eye Gallery (formerly Kahmann Gallery), GUP Magazine, Fresh Eyes, the Hungry Eye Fair, and Artibooks, Kahmann has built an integrated ecosystem dedicated to discovering, mentoring, and promoting both emerging and established photographic talent worldwide.

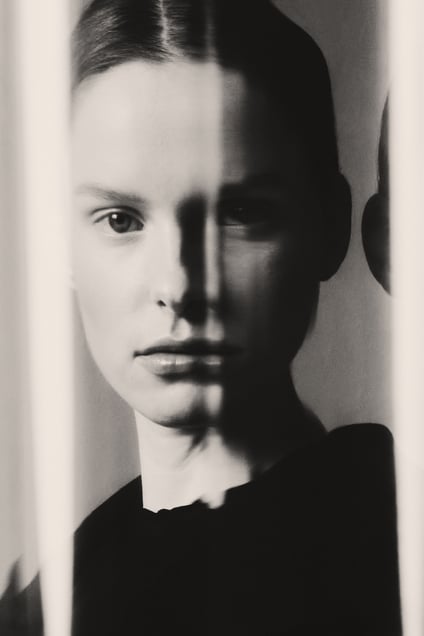

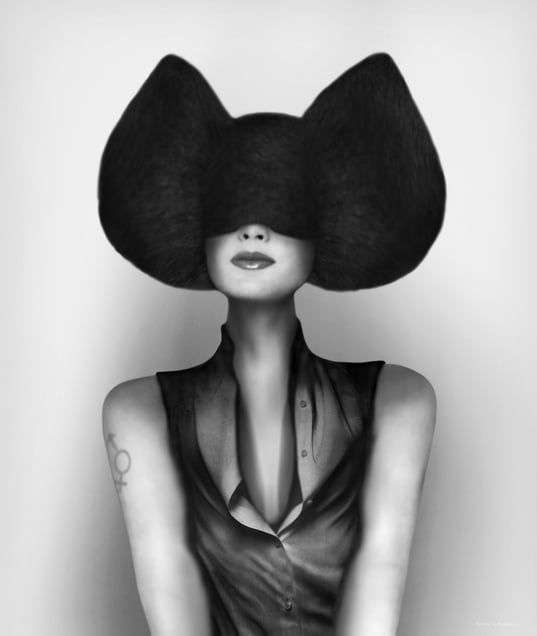

We’re delighted that Roy agreed to be on the jury of this year’s LensCulture Black & White Awards. For this interview, he spoke with LensCulture’s Jim Casper. Here is an edited version of their conversation, along with examples of just a few of the many artists you can discover at the Hungry Eye Gallery in Amsterdam.

Jim Casper: First of all, can you tell me a little bit about your personal journey with photography? What first drew you to this medium?

Roy Kahmann: Well, my personal story is a long story, Jim. I started in design. I started at one of the best design agencies as a junior, junior, junior at the end of the 1970s. And at that time I met a few big artists and one of them was Ed van der Elsken. I helped in creating his book “Amsterdam,”which became a famous book. And yet I was just an assistant of the big designers. I remember that I did a spread of a book with one of Ed’s pictures, and I cut off a piece of the picture because I thought that was a better layout. So Ed killed me for that. He said, “Who the fuck are you? Don’t crop my photos!”

And I think that was the beginning for me to see really good photography from the perspective of people who really have an eye. He made me look differently at imagery. I bought my first picture from him. And in the beginning of the nineties, on my first trip to New York, my wife and I wanted to buy some art and we ended up buying two pictures at the Howard Greenberg Gallery. And at that time, I saw that in the States, there was already an art market for photography was much bigger than it was in Europe.

JC: And since then, you’ve built an ecosystem. You’ve got galleries, book publishing, art fairs. I wonder what drives your passion to invest so deeply in this world?

RK: Well, I think I missed something in my head. (Laughs) I’m a bit crazy on that, but no, no, it is really a passion. I love to help people getting into the market and help them to survive in the big mess of the art market, and help them to find their own signature, and help for publications. So after starting the gallery, I started GUP Magazine together with two partners because there wasn’t a magazine for emerging talents here. And I thought, well, if nobody else is making a beautiful magazine, let’s do it! We did it all in our spare time in the evenings. And it was a lot of fun to make it. And yeah, that was 20 years ago that we started.

JC: You’ve helped a lot of people build their careers.

RK: Yes, I see a lot of artists, a lot of photographers, they need a sort of a coach next to them, a partner, and that can be a curator, or it can be helping them financially, or building up their name in publication, or in their storytelling. And that is something that I still love to do for certain people who I can help.

JC: Why do you think black and white photography is so special, both as an art form and as something people want to live with and collect?

RK: Well, the question, what makes black and white so special — It has been asked many times, and one reason is a really practical one. I collect a lot. My wife and I have, I think, nearly 10,000 works. We have a lot. And the reason that we only collect black and white is you easily can put pictures from 1910 to 1950 to the present day, next to each other. They all fit together visually. So that’s a really practical thing. If you do collect color — and I have a few beautiful Vivianne Sassen works in color — it’s harder to make them fit on the wall with other photos. It’s maybe my aesthetic eye that insists that color images have to fit with other color images. And with black and white it’s no problem.

JC: That’s very interesting. And it makes sense from a collector’s point of view. But why do you think so many photographers, even today in our digital world, in our color-saturated world, still choose to work in black and white?

RK: That’s a question you have to ask them, but I think black and white is easier to connect — in a series, in a book, on a wall. I see a lot of photographers, they shoot inside, outside, models, landscape, stills. If you tried to put them together in color to make them a series, they have to share a certain style, working together as a real series that getting the coloring, the color, the grading all the same. And if you make it black and white, it’s easy. It’s easier to combine all these different lightings and situations where you shoot in one series.

So there’s that practical thing again where yeah, it hangs together more easily. But it’s also taste. It’s all about taste. People love black and white or they love color. At the Hungry Eye fair 10 days ago, which attracted a lot of young collectors in their 30s and 40s, we sold more color pictures than black and white. My personal taste is still for black and white. Well, you can see what’s here in my gallery. We show about 80% black and white.

JC: What advice would you give to photographers who would hope to have their work discovered by someone like you and shown in the gallery?

RK: First of all, I look for an authentic way of working. I’ve seen a lot of people who just copy and copy in a way that shows they really looked carefully at other successful photographers. So be authentic. That’s one.

Another thing is that making one, two, or three really good images is not a big problem for anyone. You and I can make fantastic pictures with our iPhones. But it’s hard to make a series. If you can make a series that is consistent and authentic, then you have my eye, then I see the talent.

Then as a last thing, I want to know what the photographer can make after this series. So for example, I saw a really nice series recently. I loved the idea. Even though the series was fantastic, I asked the photographer, what are you going to make next?

JC: Yes. You want to see if they have staying power. As a juror for the LensCulture Black & White Awards, are you looking for anything in particular?

RK: I’m always on the look. The thing is you’ve got to say stay hungry and that’s my middle name. I’m hungry to see new talents. To find new talents.

Black and white photography is powerful for me because it always feeds my eye. There are people who say everything has been photographed already. So far it’s not true because I see so many new talents coming and … this is not done yet.

JC: If a young collector asked you why they should start with black and white, what would you tell them?

RK: Well, I sometimes give a lecture about collecting. And I think first of all, if you start collecting, look at what’s done before, look at the grand masters, William Klein, Evans, what they did. And then I always say follow the ones at your own age. So I have a young collector, he’s 32, and I have an artist in the gallery who’s also 32. I said, look at her work and it’s nice. You can grow with somebody. In the time that I started collecting, first of all, I started looking at 1950’s and 1960’s pictures, and then I started to look at photographers my age. It’s really nice to see them grow and you grow with it.

JC: I’ve had a similar experience. I started LensCulture fairly close to when you started. I met a lot of great young photographers in the early 2000’s who are continuing to make amazing work twenty years later, and it’s exhilarating to follow someone’s creative progression year after year.

JC: Any other advice you might give to photographers?

RK: Well, first of all, what I said also to my collectors, see what has been made in the past, study the grand masters. So you have a foundation of what was really good and what was authentic and what was, and still is, timeless. Then find your own way. Always keep really close to yourself. And that’s maybe a cliché, but don’t do what others tell you to do. Follow your own instinct. And the way is really hard to go. It’s not an easy way. It takes you years. You have to be patient.

JC: Thanks so much for talking with me.

RK: Well, it was nice. And I’m looking forward to seeing the work submitted for this year’s awards.