A blistering heat is baked into Scott Rossi’s photographs of Imperial Valley. Responsible for growing 90% of the country’s winter veggies, the agricultural hub was born of ingenuity and ambition, transformed from arid desert into fertile farmland through the diversion of water from the Colorado river in the early 20th century. Like a “mirage” sprouting out of brownish-yellow haze, the bright green crops now consume more of the Colorado’s water than the states of Arizona and Nevada combined. Dreams on the Dying Stone records the collision between the region’s agricultural tradition and the stark water scarcity it faces in the throes of the climate crisis.

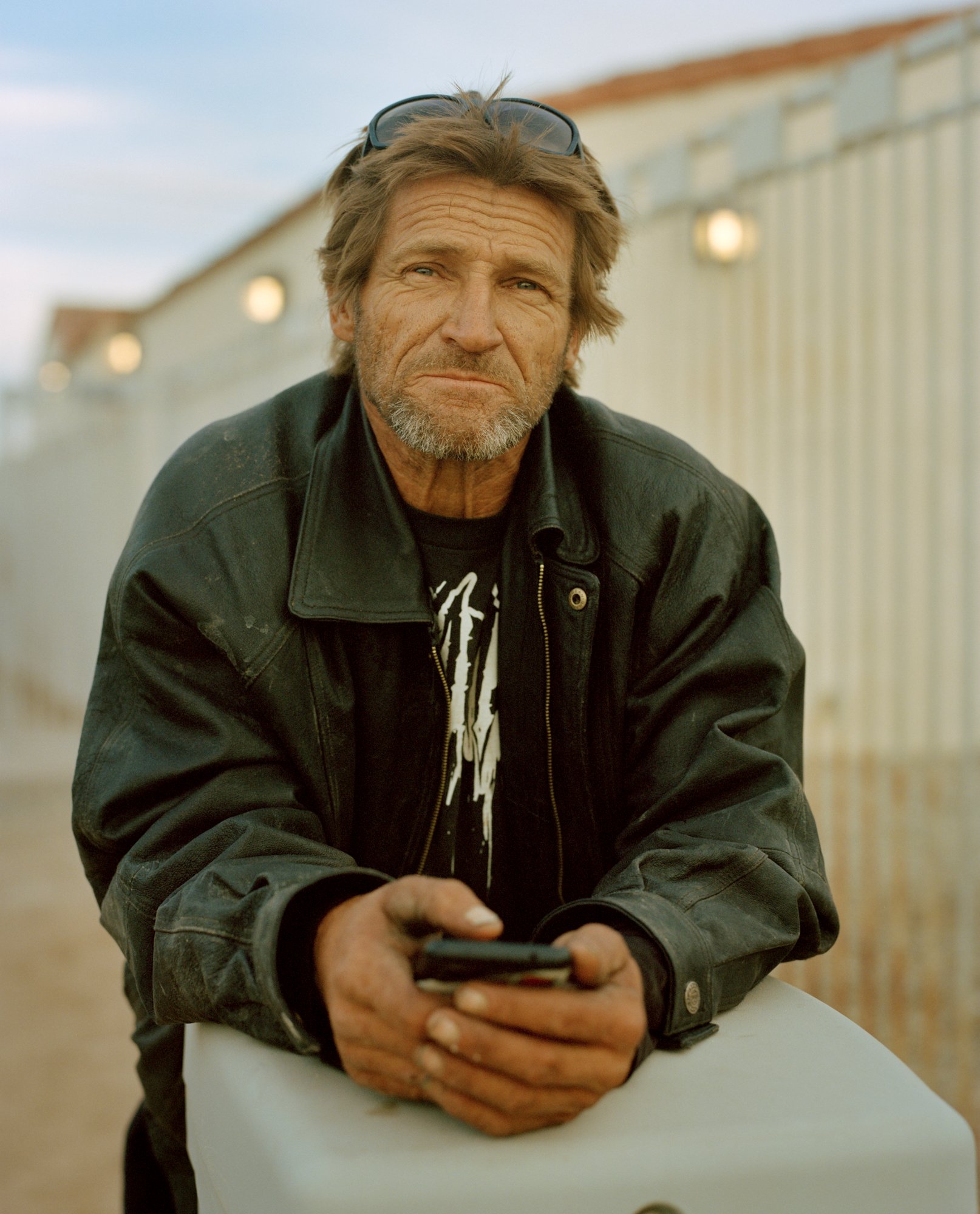

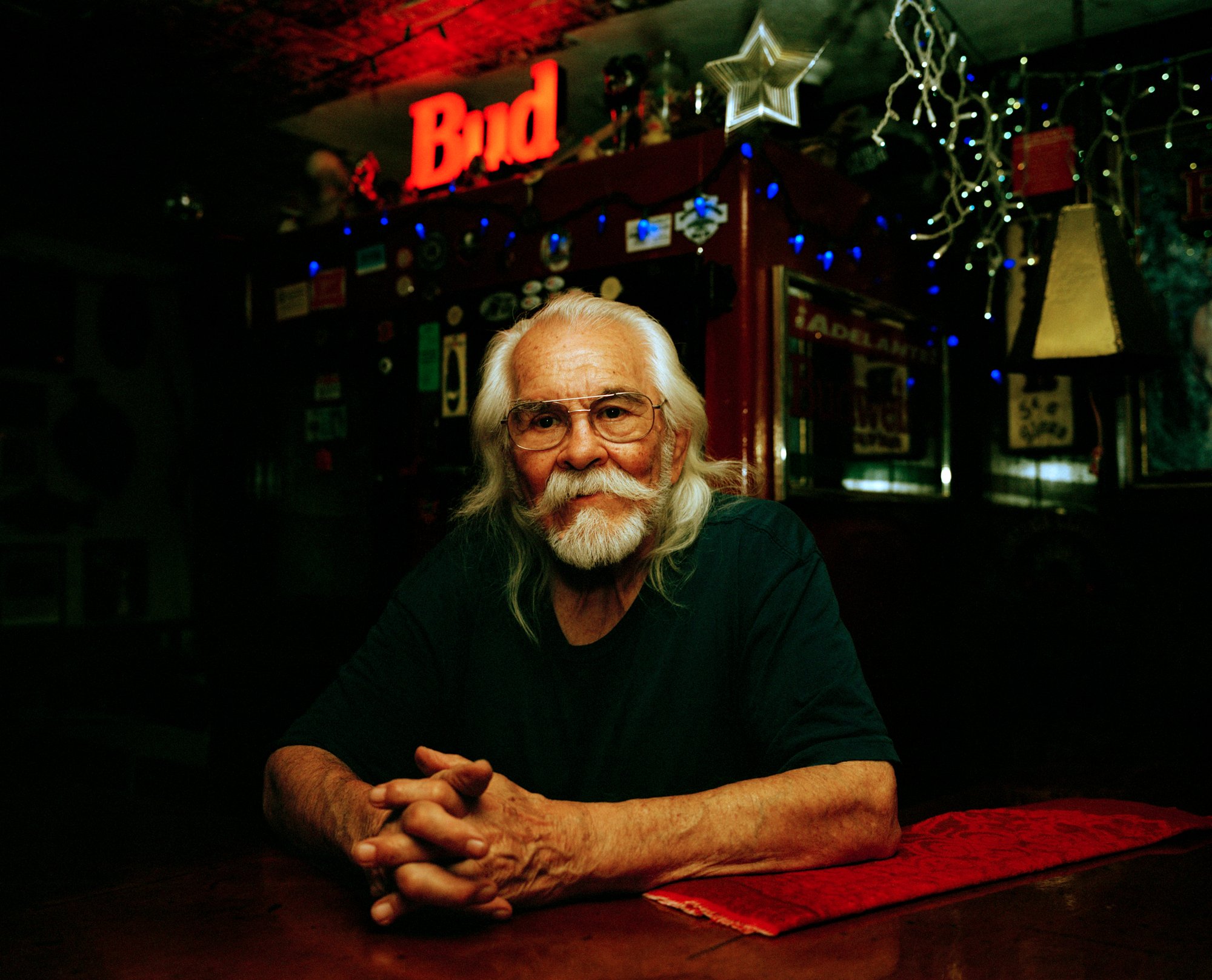

Amidst the dry, dust-filled landscapes Rossi photographs are the people that are struggling to adapt to the challenges that the community of Imperial Valley must now overcome. Faced with drought, water cuts and the steadily rising temperatures—in 2022 when Rossi started the project Imperial County had 117 days over 100 degrees Fahrenheit—the Valley’s farmers and their families are navigating an uncertain terrain as they try to renegotiate their dependence on water in a bid and survive the crisis posed by the future.

In this interview for LensCulture, Rossi speaks to Sophie Wright about his enduring fascination with the relationship between people and their environments, discovering Imperial Valley and photography’s ability to tell unresolved stories.

Sophie Wright: How did you first come to photography and what keeps you here?

Scott Rossi: My first encounter with photography was in my final semester of my undergraduate degree in psychology. I took a black and white darkroom course as an elective. My professor introduced me to the work of Garry Winogrand and Joel Meyerowitz, and I was hooked. It felt like the perfect way to express myself and be out in the world while doing it. I’m still here because I feel that I must be here. It’s a hard feeling to describe, but I do this because I feel like I have to.

SW: How would you describe the fascinations that steer your practice and how they’ve shifted over time?

SR: I’m most concerned with people and their relationship to the environment. This is what almost always drives my work. Photography is my chosen way because of its limitations. I love that photography can rarely give the whole truth or a complete picture of a topic. It’s the gaps in the storytelling that I am drawn to because it creates this beautiful tension that always pulls me in.

SW: These relationships appear in both urban and rural contexts—from a group of jazz musicians living together in South Vancouver to the communities of California’s Imperial Valley where daily life is being upturned by the climate crisis. How did you find your way to the people at the heart of Dreams on the Dying Stone?

SR: I met almost everyone pictured in the project while driving or walking around the Valley. I typically drive through the streets in the neighborhoods and along the farm roads. If anyone or anything appears to be interesting, I will stop and talk. Some interactions are brief, while others last hours. I now revisit a few people I have met. I also attend events, such as the Winter Festival and the County Rodeo, where the local communities gather.

SW: Would you say this project grows out of any previous projects or does it mark a turning point in your work?

SR: I think this project is a natural progression from my previous work. It stems from an earnest interest in a topic or a place, which is how all my work has begun, but it’s also larger in scale in comparison to my other work.

SW: Can you sketch the backdrop of Imperial Valley? What interested you about the area?

SR: The Imperial Valley appears out of nowhere like a mirage. The vast desert suddenly turns a vibrant green, lush with farms and water spritzing the ground. To the east of the Valley are dunes which lead to the shore of the Colorado River. To the west lay a dry, barren desert. To the south is the US-Mexico border, and to the north is the Salton Sea. It is one of the hottest counties in the United States and uses the most water from the Colorado than any other county along its entire length.

SW: Where did the title Dreams on the Dying Stone come from?

SR: The title for the project came from a Joy Harjo poem titled Invisible Fish. The line reads “Then humans will come ashore and paint dreams on the dying stone.”

SW: One of the challenges of documenting the climate crisis is making visible the messy network of people and things affected by our changing environment. Did you navigate any such difficulties working on this project?

SR: Yes, of course. The force driving my work is thinking of it not as a documentation of the problem itself, per se, but rather as a photographic documentation of what we are bound to lose in the face of climate change. People’s entire lives are in the Valley; whole communities with a rich culture. If things continue the way they are, soon the Valley might be forced to undergo extreme changes that could alter it forever.

Editor’s Note: This project was the winner of the LensCulture New Visions Awards 2025, Storytelling category. Discover all of the 2025 New Visions winners.