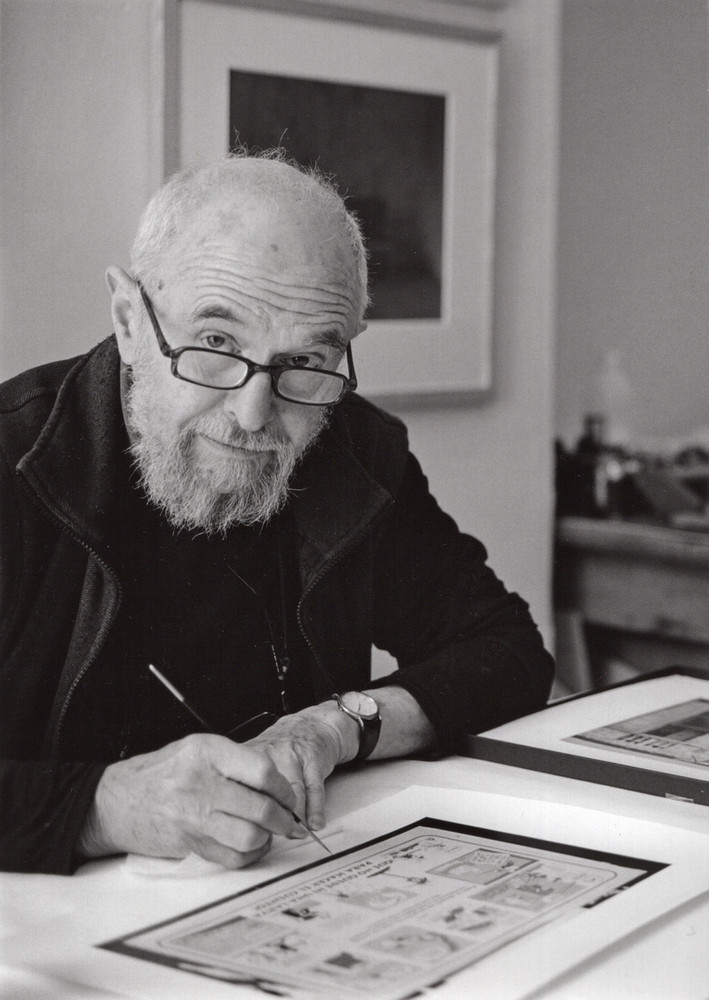

John Blakemore, who has died at the age of 88, was an inspiring teacher and an influential photographer with an international reputation. His work has been exhibited widely, including in a British Council Travelling Exhibition, and is represented in private collections. Books, which include John Blakemore (1977 Arts Council publication), Inscape (1991), The Stilled Gaze (1994), and John Blakemore Photographs 1955-2010, provide portable summaries and commentaries on his work. A major archive of his work is held at Birmingham Central Library. An inventive and compulsive image-maker with consummate mastery of the craft of photography, John won the Fox Talbot Award for Photography in 1992 and was made an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society in 1998. On retirement from full-time teaching he became Professor Emeritus in Photography at Derby University.

Born in Coventry in 1936, John was a boy who was fascinated by images from a very early age and tells how he was caned “for drawing horses in a book meant for arithmetic”; a boy who despite growing up in a house without books became an avid reader with a deep love of language; a boy who hated school yet became an inspiring teacher and generous mentor; a teenage lad who, with no thought of becoming a photographer, worked as a farm hand and kept an ornithological diary, but went on to win renown for creating images evoking the energies and forces of nature.

As was usual for young men of his generation, the trail from childhood to adulthood included National Service and in the mid nineteen-fifties he found himself serving as a nurse with the RAF in Tripoli. It was an experience that left him a committed pacifist. But it was also there, after seeing images from Edward Steichen’s ‘The Family of Man’ featured in Picture Post, that he determined to become a photographer.

He bought his first camera and began teaching himself photography in the sweltering Libyan heat.

On his return to England, and drawn to documentary work, he began working with the Black Star agency before deciding that freelance work was not for him. He returned to Coventry and over the next few years managed a photographic studio, and completed a 4-year City & Guilds course in Photography. Still concerned with documentary photography he produced and showed his first major body of work, ‘Hillfields —Area in Transition’, about the inhabitants and the post-war reconstruction of the Hillfields district in Coventry where he lived. Among other work he also documented a production of West Side Story, and it was during this period that he met Richard Sadler who became a lifelong friend and mentor. Then in 1970, after another spell in London, John took up a teaching post at Derby Lonsdale College (now University of Derby) where he remained until his retirement.

The move to teaching not only freed him of the need to earn his living as a photographer but also provided the opportunity to extend his mastery of the craft and to discover and proceed with new themes in his personal work. John proved himself a generous and approachable teacher, always willing to discuss students’ work and elicit ways in which it might be taken forward.

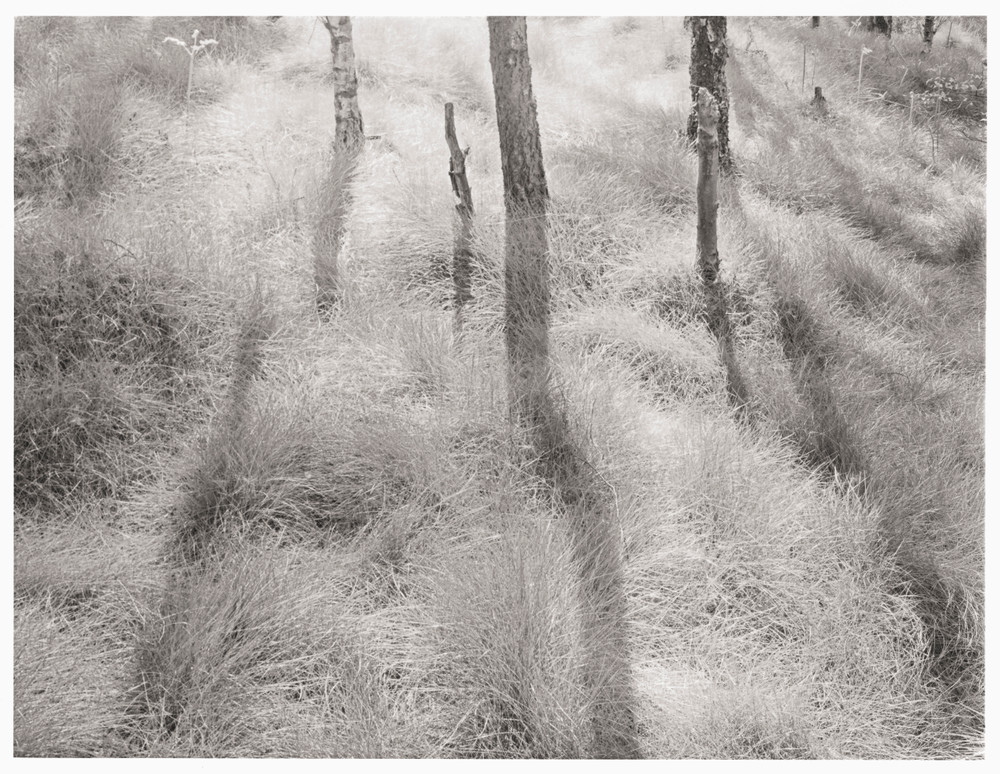

A return to personal work was instigated by an invitation from students to participate in an exhibition. He had spent the winter of 1968 in North Wales and recorded impressions of the landscape:

A land of paradox, harsh lunar landscapes, running with gurgling water, and supporting everywhere a riotous life…Limbs green with parasitic growths of moss and lichen, which weld tree and rock into one entity…wood metamorphosed into rock by the struggle for life…

John later said that it was the first time he had become truly aware of the landscape as an active vital process, and it is these impressions that inform and underpin the photographs he made in the landscape over the next decade. His photographs are never pictorial or concerned with the topography provided by the open view: he sought instead to convey the sense of the energy, of the underlying dynamic of the landscape, of the natural forces at play, and of the spiritual sense of place. The section titles in his 1977 monograph confirm these preoccupations: Metamorphoses, Primal Surge, Emergence, All Flows.

Besides teaching at University, John also began leading workshops. Participants who arrived in awe of his growing reputation found themselves in the presence of the most accessible, modest, and unassuming man — a man inclusive and generous. Nervous arrivals soon relaxed in his presence. As his work changed over the years so did the agenda of his workshops, but the earliest were concerned with the landscape where his own practice began with a ritual of acclimatisation. Having found a suitable spot, he would sit with eyes closed for about twenty minutes allowing himself to feel the contact with the ground, hear the myriad sounds of the landscape, and experience the movements of the air. It was a practice he shared and encouraged. Its purpose was two-fold: attunement to the place and the dispersal of any preconceptions as to what images might be made. Typically, a workshop would include an introduction to participants’ work, a field trip, a printing demonstration, and a discussion of photographs made on the field trip. John’s great gift lay in his empathy and ability to engage with disparate work at any level and to elicit and draw its maker into a fruitful discussion of intention and motive and to suggest a possible way forward.

In his personal work John would pursue a theme until he felt that for him its possibilities were exhausted. He stopped working in the landscape partly because he felt he could no longer justify a practice that represented the landscape as Edenic.

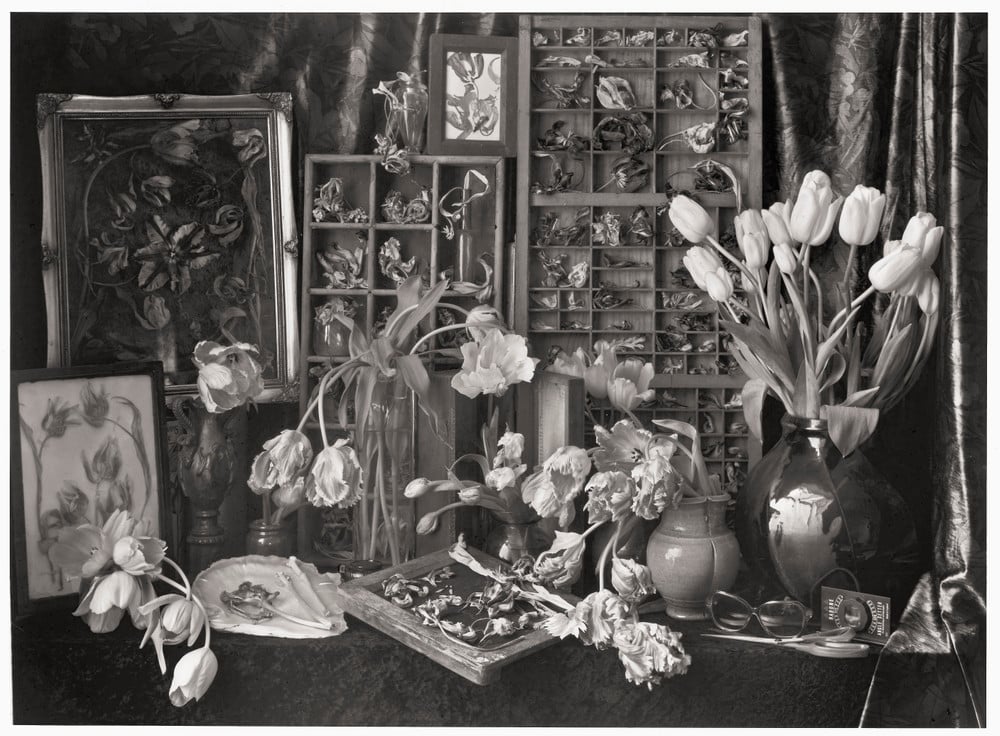

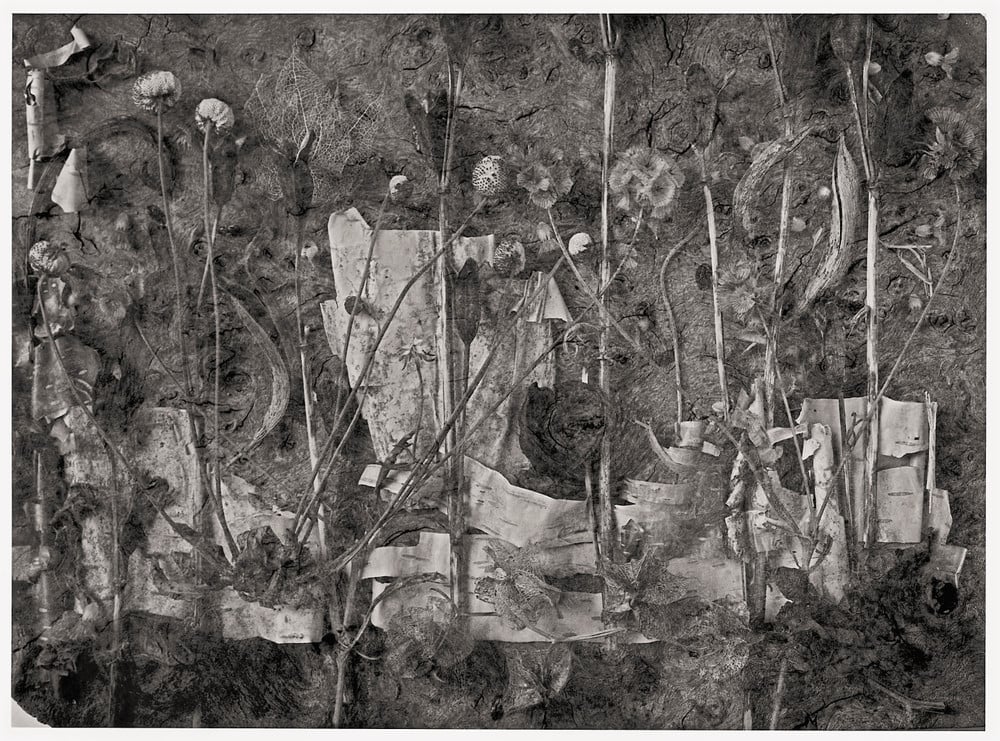

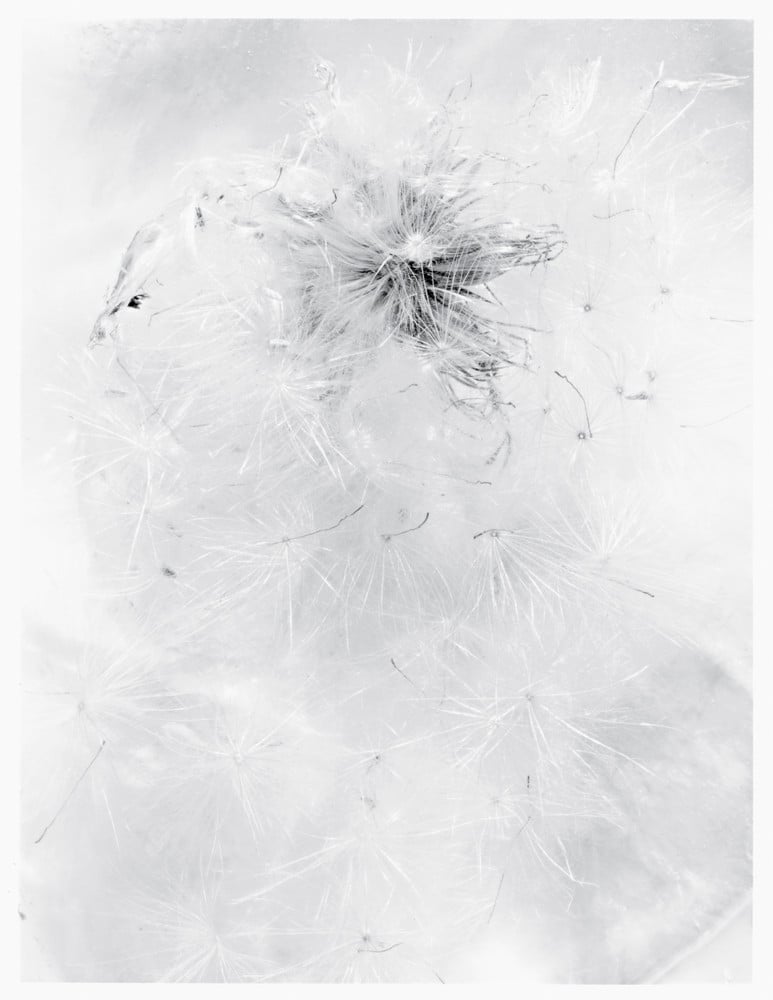

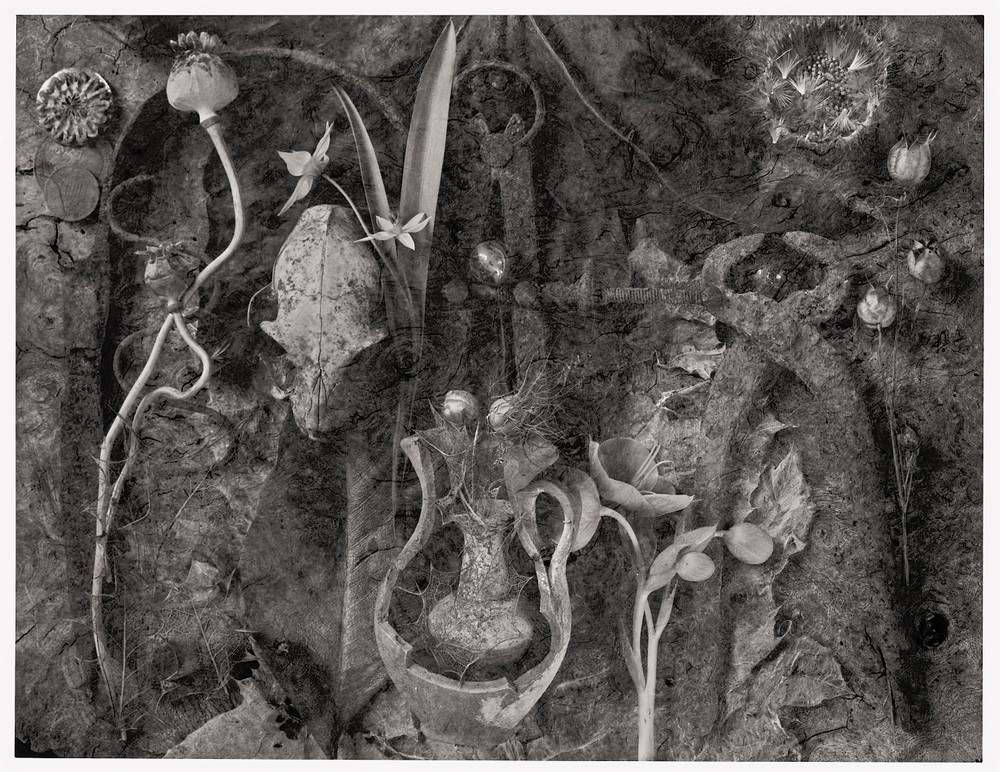

In John’s work there is always a sense of discovery and a deepening relationship with his subject. Anything from thistles in a neglected garden to a vase of tulips on his kitchen table could surprise and stimulate an investigation. Some enquiries would be short-lived, others would result in an extended relationship and prolonged image-making.

When he turned to still life. he described his approach: “To construct still life is to play, both to create and solve a jigsaw puzzle with no guiding picture.” But there remains always a sense of intimacy, of sustained connection — something which applied to every area of his work.

His still-life photographs are intense observations — the Pampas grass series have all the precision of engineering drawings — while at the same time being metaphors for his inner responses, conveying by turns a dark brooding melancholy and an airy lightness, and the mysteries of metamorphosis, of decay and regeneration.

He preferred to be thought of as a picture-maker rather than as a photographer and he described picture-making as the transformation of subject to idea to image; and to this end he became a consummate master of the craft of monochrome photography, insisting that ‘the exploration and control of process is fundamental in any medium’.

While his prints were always processed to archival standards, he was the first to remind a student over-concerned with the permanence of their work that “we do not live in an archival world.”

He exhibited widely but was never really at ease with the Gallery scene.

He sold prints at appropriate prices but was highly critical of the inflation of values in the market in fine prints, often remarking, “It’s only a piece of paper.”

John was man who could speak eloquently to large audiences about his work and answer questions with generous patience — yet he was happier talking about photographic work in the intimacy of a small group at a workshop or one-to-one across his dining room table.

With regard to the craft of photography, students at Derby were taught the fundamentals of the Zone System and, even as the age of digital photography was getting underway, John wrote a book on image-making employing the traditional darkroom practice of black and white photography — John Blakemore’s Black and White Photography Workshop. In it he discusses the three R’s of photography which are key to understanding his work — Relationship (with subject), Recognition (of the moment to make a photograph), and Realisation (of the intended image as a final print to be shared). He took no issue with digital capture — what concerned him was the ease with which apparently unsatisfactory images might be discarded before the questions they raised were confronted, and the lessons of initial disappointment learned.

The last phase of his work saw him confining his practice to his garden and to the exploration of the play of light in his living room. Although he had a darkroom and continued to produce prints, he forsook his MPP plate camera with its single Symmar lens for an aged but reliable Nikkormat. He photographed in colour and took his films to be processed and printed at Jacobs in Derby. He edited (even cut up) and sequenced the resulting prints and devoted himself to making handmade books.

He had always seen his photography as a thread of sanity through a chaotic life, and the eventual production of a retrospective book meant not only selecting and editing work but facing the sometimes uncomfortable reminders of a shifting life. It also afforded the opportunity for him to contextualise the images and their making with observations in exquisitely written texts.

While his work and contribution to photography was widely acknowledged and he earned international renown, he remained always modest and unassuming; throughout a long career he was always accessible and, above all, generous.

Words borrowed from his craft book convey so much of the man so many knew. In its dedication he pays tribute to “all the students who made it necessary for me to discover ways of talking about picture making,” and in its introduction he is almost apologetic: “Ideally this book would be a conversation. We would be sitting around a table spread with prints discussing the hows and whys of their making…”

—John Comino-James, January 2025

John Comino-James is a photographer and author of several books, including A Question of England. He met John Blakemore in 1979, and Blakemore became his mentor and life-long friend starting around 1989.