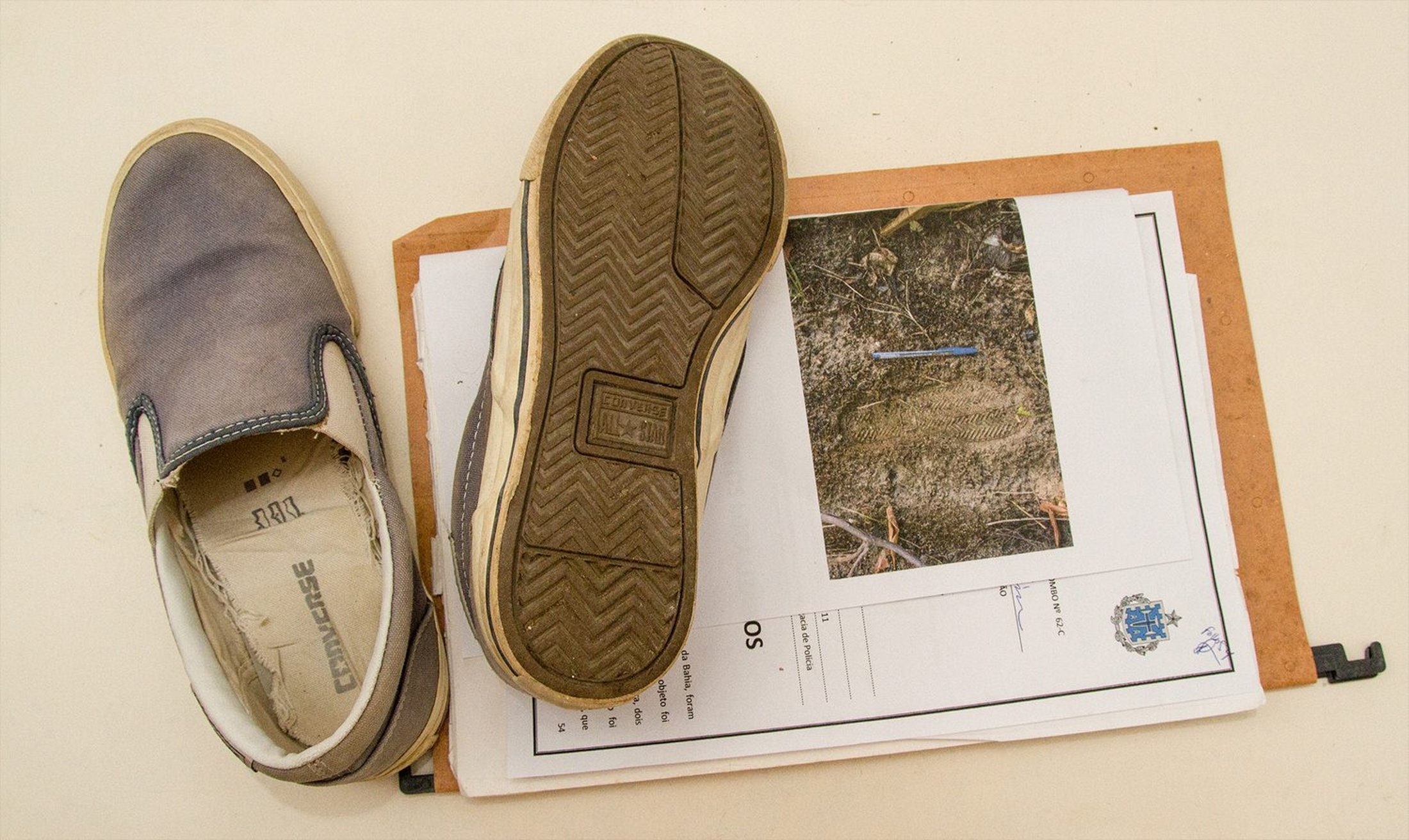

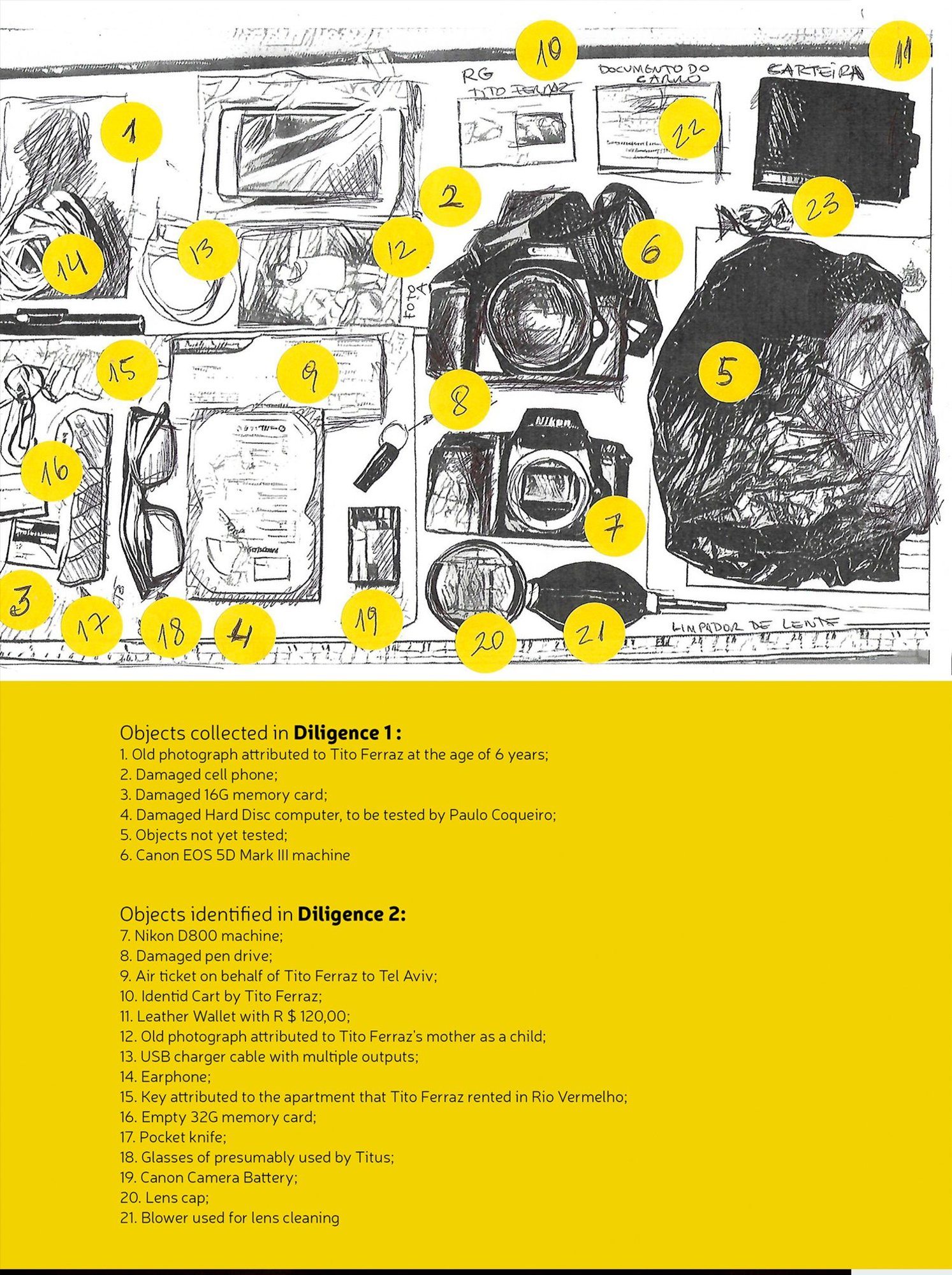

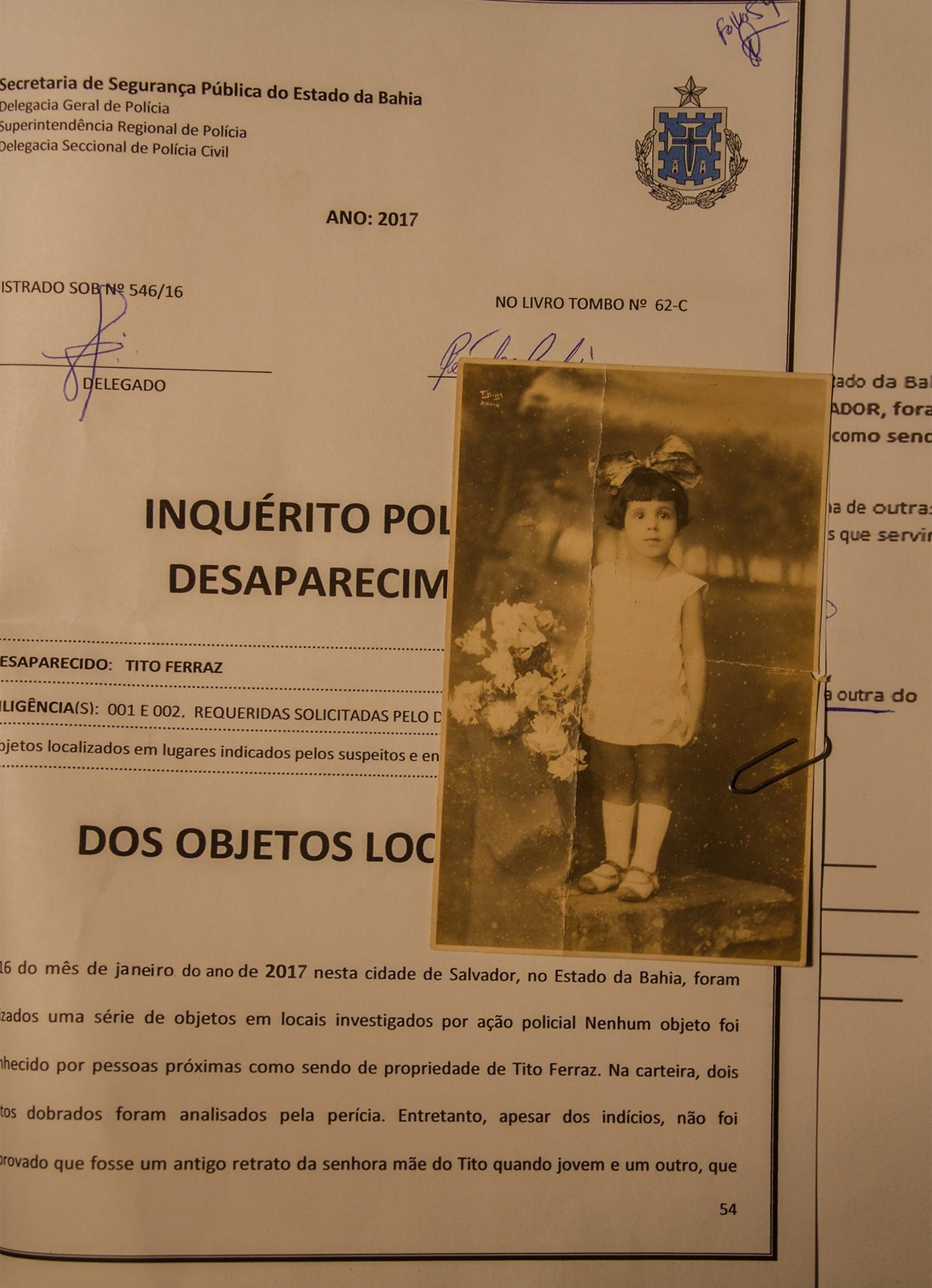

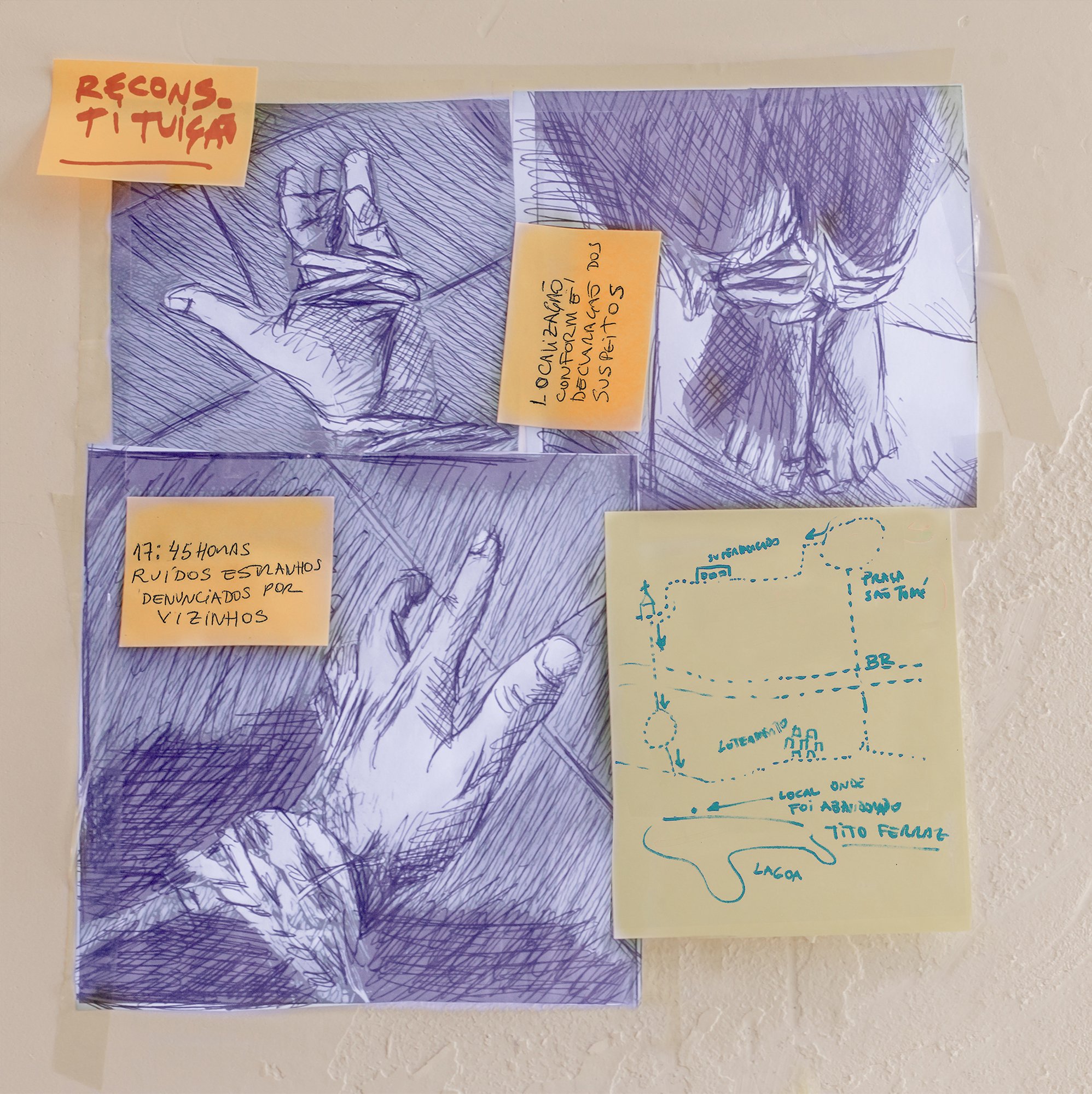

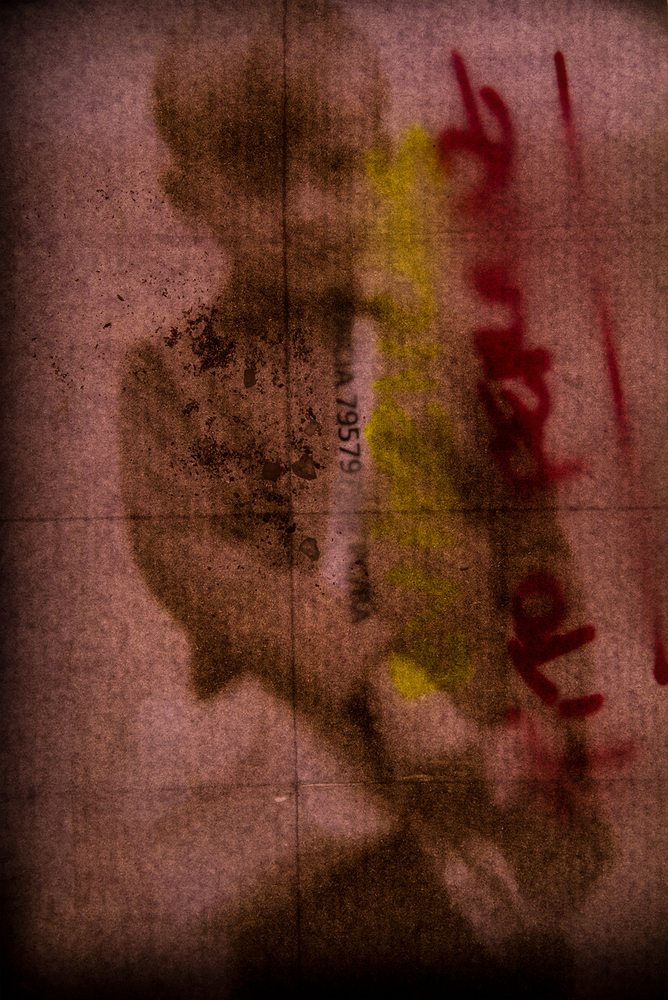

“Remember, I am lying to you.” Politically-entrenched photojournalist Tito Ferraz went missing from his home in December, 2016. Over the course of several months, the outspoken photographer communicated across his network of 5000 Facebook friends, dropping breadcrumbs which would ultimately end in his sudden and dramatic disappearance. A threatening letter arrives. His apartment is broken into. Hard drives are destroyed. Evidence is collected. Everything gets documented through forensic-style photographs. Flyers go up through his community in Bahia, Brazil demanding answers and justice. What happened to Tito Ferraz?

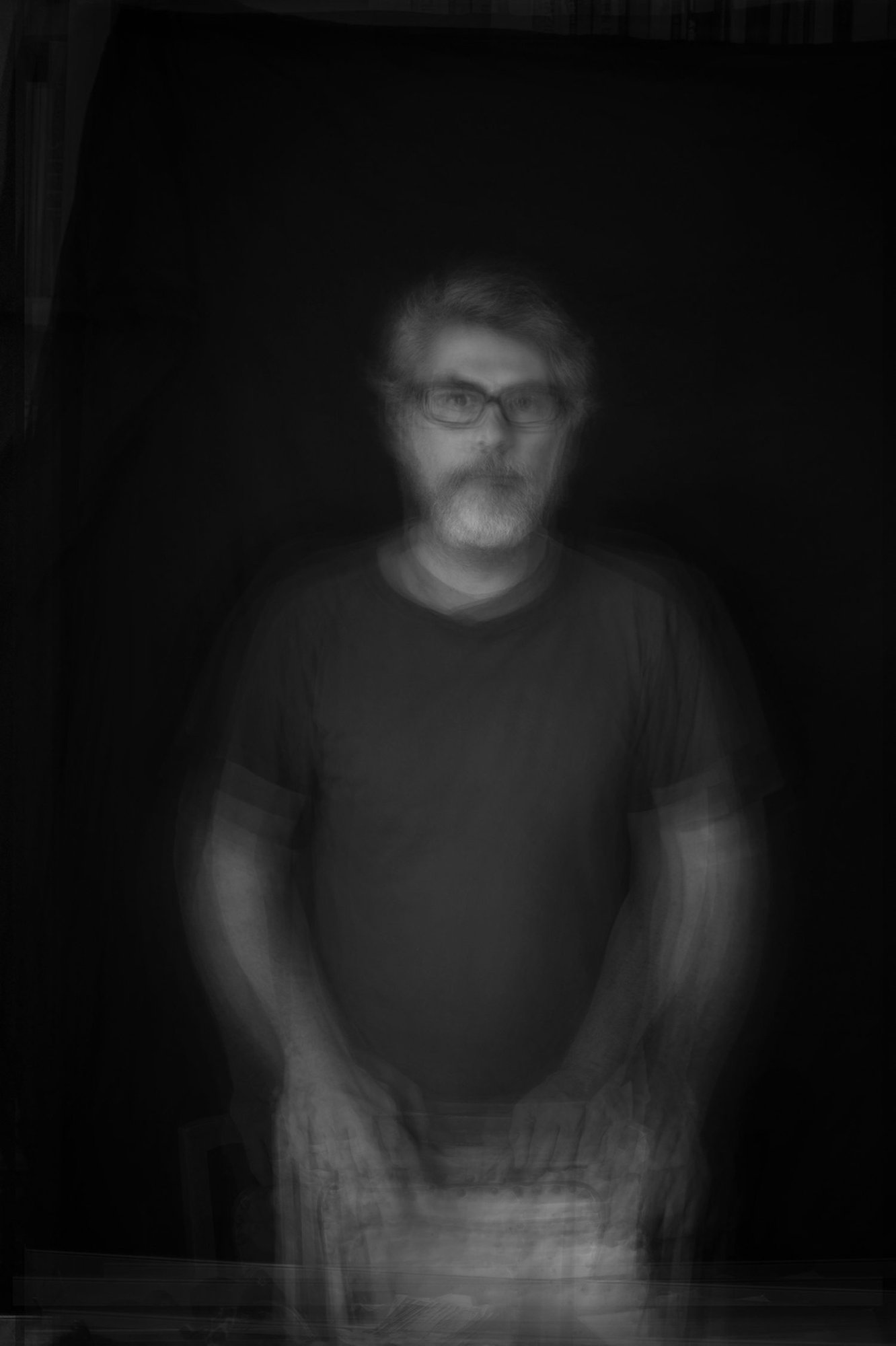

But the more pressing question is, who is Tito Ferraz? On July 7, 2020, I met mastermind and artist, Paulo Coqueiro, through Skype after earlier communications via email and WhatsApp messaging. He appeared on my mobile phone in near monochrome—wearing a black t-shirt, ebony-rimmed glasses, a salt and pepper beard, sitting in a room of alabaster walls with a smooth, white air-conditioner hanging high beside him. Save for a few books on a distant shelf, everything surrounding him was either black or white which is exactly what I needed. My head had been swirling in the gray.

Tito Ferraz is not real. During a two-year project, Não Minta Para Mim (Don’t Lie to Me), Coqueiro created this fictional character, pressing brilliantly deep into questions surrounding the implied truthfulness of a documentary approach to photography. “I was interested in the power of images to forge truths; how it’s possible to write using photographs.”

Coqueiro took this a step further by meticulously crafting a fake Facebook account. He built a friend list of photographers, curators and others within the art world for a more believable profile, entering into a handful of virtual conversations with unsuspecting ‘friends’ where he often directed the exchange towards questions on fiction in photography. He would invite them for coffee, book launches, exhibitions—but Ferraz always came up with some sort of an excuse, explaining how they had just missed each other in his apology the next day, sent through Facebook Messenger.

Coqueiro being the one orchestrating these missed connections would, himself, visit the meeting places and take photographs to post to Ferraz’s profile for yet another layer of legitimacy. I lean in closely to listen, trying to keep up with the fluid movement between ‘he’ and ‘me’ as he maintains a clear distinction between character and reality. At times, those two words were the only thread I had to keep fact and fiction from getting tangled up in my own understanding as he shared an image of a newspaper clipping or spoke of a police investigation. Why do we default to believing in truths despite knowing the messenger has been feeding us lies? The story folds you into it.

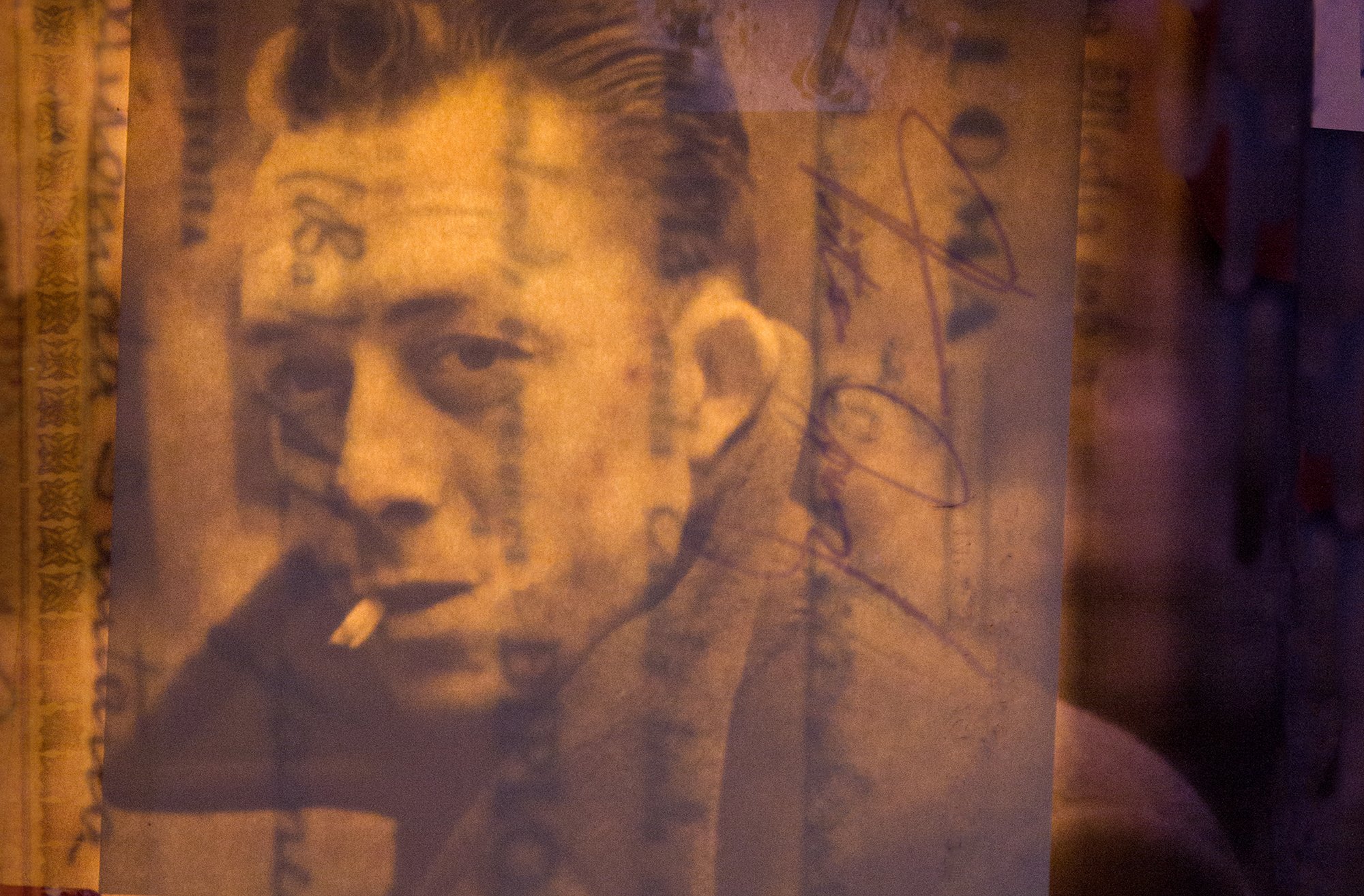

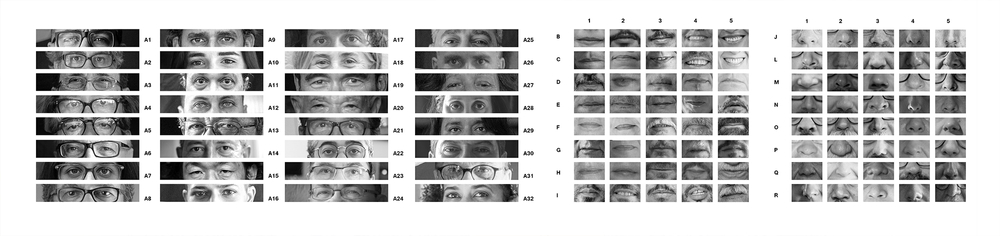

In the chapter following Ferraz’s disappearance a hard drive is recovered containing the portraits of forty-one people which Coqueiro has bound into a book. He has also created a series of short films, one believable enough to have me scratching my head once again: “Is Ferraz real?” He records forty-one people who have befriended the fake Facebook account and interviews them as witnesses of Ferraz’s existence (none of them knew about the fictional character).

“I would not say I use the character to lie, but to demonstrate the fragility of an alleged documentary truth. Or how credulous we are in the face of photographic images.”

Coqueiro released a portrait of Ferraz in the style of a police sketch, crafted from various facial features of each of the photographers he interviewed, having taken their photos while visiting their homes and studios. When they gaze into this likeness of Tito Ferraz, they unknowingly look at fragments of themselves.

In a striking reversal of roles between the rebellious photojournalist and Coqueiro’s act of fiction, Don’t Lie to Me became viewed as a political threat. Mere hours before the opening of the Winds of Time exhibit at Lianzhou Foto Festival in 2018, censors confiscated some of the work without explanation. Weeks earlier, by coincidence, renowned photographer Lu Guang went missing after stirring up dust by speaking out on controversial issues in China. It would be a year before he re-emerged from police detention, punished for showing that which does not want to be seen.

I, myself, posted a photo to a public Facebook page earlier this year after a virtual colleague asked me to take a selfie holding a ‘Where is Kajol?’ sign. Bangladeshi journalist, Safiqul Islam Kajol went missing under similar, mysterious circumstances and was discovered nearly two months later in police custody. He stands accused of “engaging in extortion by obtaining information illegally and publishing false, intimidating, and defamatory information via Facebook and Messenger,” as reported by the Dhaka Tribune.

Deceit can reveal a great many truths: Tito Ferraz has not yet been found.