A house engulfed by creeping vines, a snake crossing a desolate road, and a woman with her hands folded in prayer are just a few of the cryptic scenes that populate the photographer Rosie Brock’s series Soliloquy. Comparing photography to the process of writing fiction, Brock weaves together an atmospheric tale with her mix of portraits and landscapes.

Taken individually, the images hint at but do not reveal that something is amiss. As a whole, they build an intriguing mystery of the aftermath of tragedy. In a play, a soliloquy is the act of speaking one’s thoughts aloud. Starting from her own familial connection to southern Georgia, Brock has fashioned a haunting narrative of the overlapping forces of religion, community, fact and fiction and the all too real acts of violence against women.

In this interview for LensCulture, Brock speaks to Magali Duzant about her deeply-rooted connection to Georgia, photography as writing and the cultural influences that underpin her project.

Magali Duzant: Can you introduce yourself? How did you find your way to photography?

Rosie Brock: Originally, I started taking pictures as a freshman in high school because I wanted to have glamorous portraits of myself to post on Facebook. My dad bought me some flood lights from Home Depot and we turned our basement into a makeshift studio, complete with a fan and rack of costumes. I’d photograph myself, my younger sister Lily, and our friends, edit the selections, and then post them online. Over time, I began to become interested in photography as a fine art, and enrolled in classes at school and programs during the summer, then went to art school for college, and eventually, to graduate school.

MD: Your project statement opens with the line, “My practice is driven by a desire to craft fictional narratives rooted in documentary origins.” Can you tell me about the origins of this project and how they influenced the seed of your narrative?

RB: This project is loosely inspired by a town in Southwest Georgia called Richland where the maternal side of my family has lived for generations. As a child, I visited every summer for family reunions and always found it to be extremely mysterious and intriguing. When I moved to Georgia to begin the MFA Program at the University of Georgia in 2019, I initially set out to create a more traditional documentary about the town.

On long weekends, I would drive the roughly three-and-a-half hour route from Athens to Richland, and stay with relatives or at my Grandaddy’s trailer which was on an isolated pine-tree farm. After a few visits trying to envision the project in a more documentary form, I realized that my creative approach isn’t rooted in strict factual storytelling. Instead, I’m drawn to learning about actual events, people, or family lore and expanding on them, remixing and blending them with other elements until they evolve into something new entirely.

MD: Tell me about some of the real events this project is based on.

RB: During one of my visits to Richland, I found out about the murders of three teenage girls in the 1980s, and that topic of violence against women and misogyny in relation to the South is very resonant to me. Simultaneously, many of the conversations I was having with people I was meeting out on the road drifted into the territory of tragic tales of women who met violent fates at the hands of men. Religion, specifically evangelical Christianity, was also a topic reemerging again and again and will always just be bouncing around in my mind due to my upbringing.

All these things—as well as realizing my interest in making photographs is akin to writing fiction—led me to develop a narrative set in the imagined town of Tarwater, Georgia. Some of the pictures were indeed made in Richland but the majority were in different towns throughout the state. The story centers on a failed Christian commune led by a man who claimed to speak with the spirit of Mary Magdalene. After a decade of attempting to create a utopian society, the commune collapsed following the murders of three young women. The ‘present day’ of the narrative is supposed to be 1993 when an unnamed narrator returns to Tarwater to investigate the unsolved crimes and their possible ties to the commune.

MD: How did your narrative develop? Do you create the story in full before photographing, after the fact of photographing, or does it continue to build and change as you make images? Are you storyboarding your scenes, staging images, or responding in the moment?

RB: The narrative came together gradually in fragments. After each drive or photography session, I’d return home and write about what I’d seen, letting those impressions stew for a while. On the next outing, I’d encounter something new that seemed to naturally connect with the story already forming in my mind. This process continued over time, slowly shaping itself into a loose narrative that I could follow.

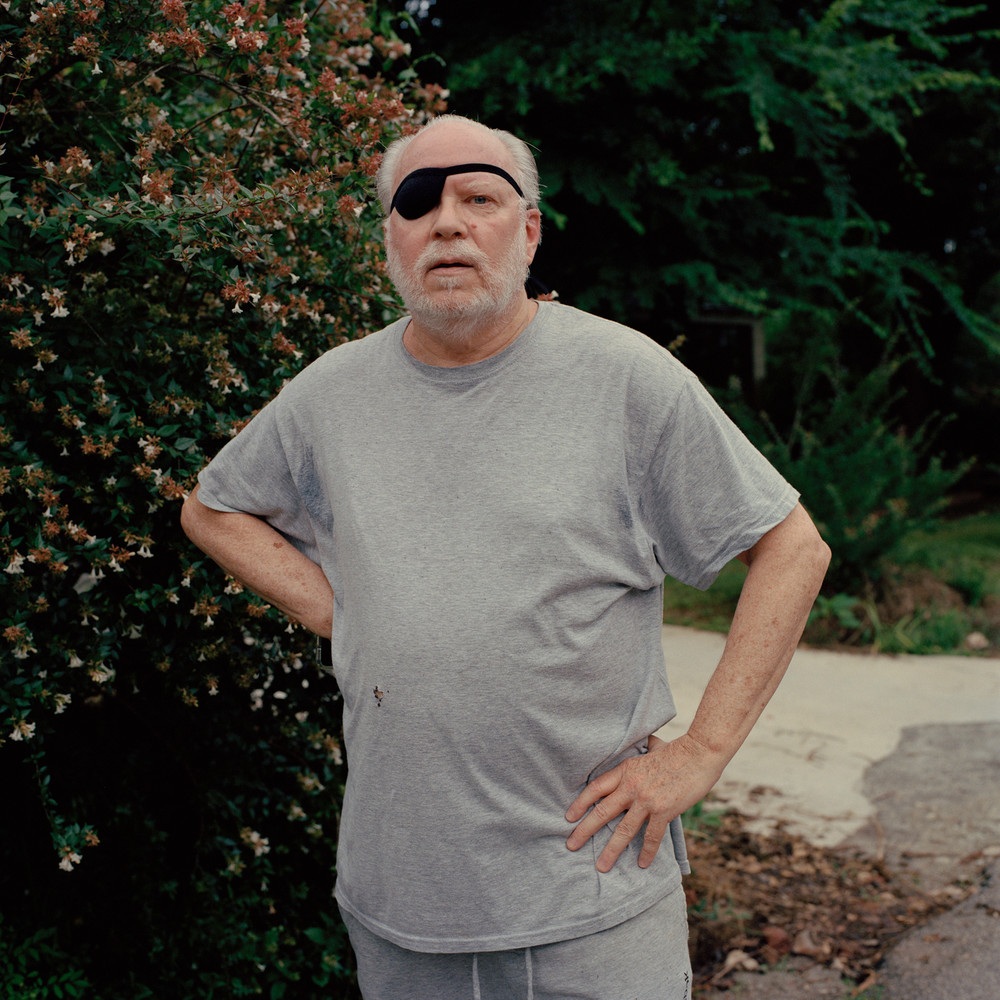

Often, I’d begin with just a small idea, an image or a character I hoped to find. I kept a running list of visual prompts or personalities I imagined might emerge, and I’d head out with the hope of crossing paths with them. Things like, “an old man with a long beard in front of flowers,” or “a woman who looks like Tammy Faye Bakker.” And somehow, almost magically, those exact figures would appear, standing by the side of the road or in a town square. I believe in setting an intention and trying to energetically will something into existence. Occasionally, I’d cast specific people and stage scenes, but much of it came from that spontaneous, almost serendipitous process.

MD: The work has a cinematographic atmosphere, do you see your role as a director? As the cinematographer? Both? Are you collaborating with your subjects as you encounter or cast them?

RB: I see film as the ultimate art form since it activates almost all the senses. I wanted this work to evoke the feeling of watching a movie. I drew a lot of inspiration from cinema and television, often referencing a folder of film stills I kept on my phone to guide the atmosphere and tone of the images. In that sense, I do see myself as a director; venturing out into the world as if it’s a kind of open-air set, encountering people along the way and inviting them to step into a moment I’ve envisioned. While some of the scenes are more spontaneous, there’s definitely a sense of collaboration with the people I photograph, whether I meet them by chance or cast them intentionally.

MD: You’ve built a persuasive, enigmatic world in Soliloquy. Can you tell me about your connection to this landscape and how it informs or guides your image-making? Have you considered working in a similar style in a place you are unfamiliar with?

RB: My connection to the landscape in Soliloquy is deeply personal, shaped by memory, family history, and years of quiet observation. When I see pictures of the landscape it genuinely makes my heart ache. That familiarity allows me to look beyond the surface and notice subtle details and emotional undercurrents that might otherwise go unnoticed. It plays a central role in my image-making, as I respond not just to how a place looks, but to what it holds for me emotionally and symbolically.

I’ve thought about applying this approach to places I’m less familiar with, and I’m curious how the process might shift without that sense of history to guide me. I imagine it would take more patience and attentiveness, to allow the place to gradually reveal itself rather than imposing a story onto it. That kind of challenge feels creatively exciting, and it’s something I’m open to exploring. I’d especially love to photograph in the American West.

MD: Can you tell me about the work’s written components and how you wrote or compiled them? Is there a final format that you would like your viewer to experience the work in, say a book, an installation, or a website?

RB: The written components were developed alongside the photographs, often as reflections after a day of photographing. I would come home and write down observations, memories, or fragments of dialogue, sometimes based on real interactions, other times partially imagined. Over time, these pieces started to form a narrative thread that paralleled the visual one. Writing became a way for me to process what I was seeing and feeling, and to deepen the tone of the work. The text primarily takes the form of short stories, told through the voices of various fictional town residents. Among them are the commune’s leader, Jimmy, and the unnamed narrator, each offering their own perspective on the history and atmosphere of the town.

As for the final format, I see the project ultimately taking the shape of a book. I like the intimacy and permanence of the book form, it allows the viewer to sit with the work slowly and return to it over time. I’ve also thought about adapting it into an installation, where the writing and images could interact more spatially, but for now, the book feels like the most complete and immersive way to experience the project.

MD: As you created Soliloquy, what were you reading, watching, or looking at to inform the project?

RB: I spent a lot of time in my room or on my front porch immersed in various forms of media that connected to the work. Two novels that deeply influenced the tone and themes of the project were The Violent Bear It Away by Flannery O’Connor and Other Voices, Other Rooms by Truman Capote. Importantly, I made the name of the town ‘Tarwater’ as a reference to the last name of the main character in O’Connor’s novel, who fashions himself as an evangelical prophet. In terms of movies and television, the first season of True Detective is sort of a bedrock reference in my practice, and I was rewatching Sharp Objects around that time as well. For Soliloquy specifically, I was influenced by movies such as The Night of the Hunter and Carnival of Souls. Of course, a David Lynch mention is fairly obligatory.

On the photographic side, I was especially inspired by Deanna Lawson’s portraiture, Tanyth Berkeley’s series The Walking Woman, Send Me a Lullaby by Emma Phillips, Wood River Blue Pool by Jo Ann Walters along with the related book of writing, Blue Pool Cecelia by Emma Kemp. Music also played a vital role in shaping the project. Classic country and folk music were especially meaningful, and I curated two specific playlists that I would listen to while driving—helping to set the mood and rhythm of the work.

MD: For a project that encompasses references to and inspiration from both literature and cinema, what was it that made photography the right medium to craft this narrative?

RB: Photography captures both the tangible and the elusive, anchoring the imagined narrative in real, physical places and faces while leaving space for mystery and interpretation. My interest in the photographic medium is its ability to straddle both veracity and fiction, which is a theme central to the project. That said, my *secret* dream is to adapt this story to a mini-series format.