The woman running through Scott Offen’s Grace, at times decked out like a Nordic goddess brandishing a sunflower in her hand, at others glimpsed as a naked back hidden by large leaves, is on a journey beyond the confines of daily life. Flitting between stuffy interiors and expansive, wild landscapes, she shapeshifts and plays through different emotions, empowered as the protagonist of her own fairytale. Patterns—of clothes, of skin, of tree bark—are brought to the surface, drawing our attention to cycles of time and change.

These carefully-considered monochrome pictures are the outcome of a seven-year collaboration between husband and wife of more than 30 years, Scott and Grace Offen. In response to a teacher’s suggestion to photograph his family, Scott picked up his camera and began to photograph Grace out in nature where she felt free. The photography project evolved into a shared-space of creativity where Grace could grapple with the slippery experience of getting older as a woman. Through an intimate process of co-creation, the pair quit the quotidian to wander and play their way through the questions we face as we age.

In this interview for LensCulture, Offen talks to Sophie Wright about the origins of the book, the representation of age and the importance of play—in both life and creativity.

Sophie Wright: How did you get to photography and what’s kept you here?

Scott Offen: I picked up photography in 2014. I’m not entirely sure why, but I did. I had no experience of shooting but I started taking night classes, starting with street photography which I did for five years. A couple of years afterwards, I photographed people who lived on the street and my focus gradually narrowed, until I was really photographing just a very small group of people that I was very close to. In 2017, I applied to study, was accepted and retired from my job as a portfolio manager in the financial world. I walked away from it all to do photography.

SW: How did Grace emerge out of these interests?

SO: When looking at my street project, one of my professors in my sophomore year said to me, “You’ve made a family of choice here. Why don’t you photograph your family of origin?” She told me to look at Harry Callahan, and the teacher of her teacher, who was Emmett Gowin. I discovered a bunch of other photographers along the way that really interested me. Lee Friedlander made a body of work about his wife Maria that’s really lovely. Seiichi Furuya made a body of work about his wife Christine, who suffered from a psychiatric illness, eventually committing suicide. I tried to get different takes on how to do it—and how to do it also in my own way. I didn’t want to copy anybody. I had tried that and it was just terrible.

When I started, I thought I would photograph my family, but my children all said no. But Grace wanted to do it. We’d been together for 42 years at this point, married for more than 30. We have a relationship of trust and intimacy that could only be built up over those many years so it was actually pretty easy for us to start to do this together. We started in around 2017 and the last photograph in the book was taken in 2023.

SW: How did you define the parameters of what you were working with? How did the themes of the project evolve and ripen over time?

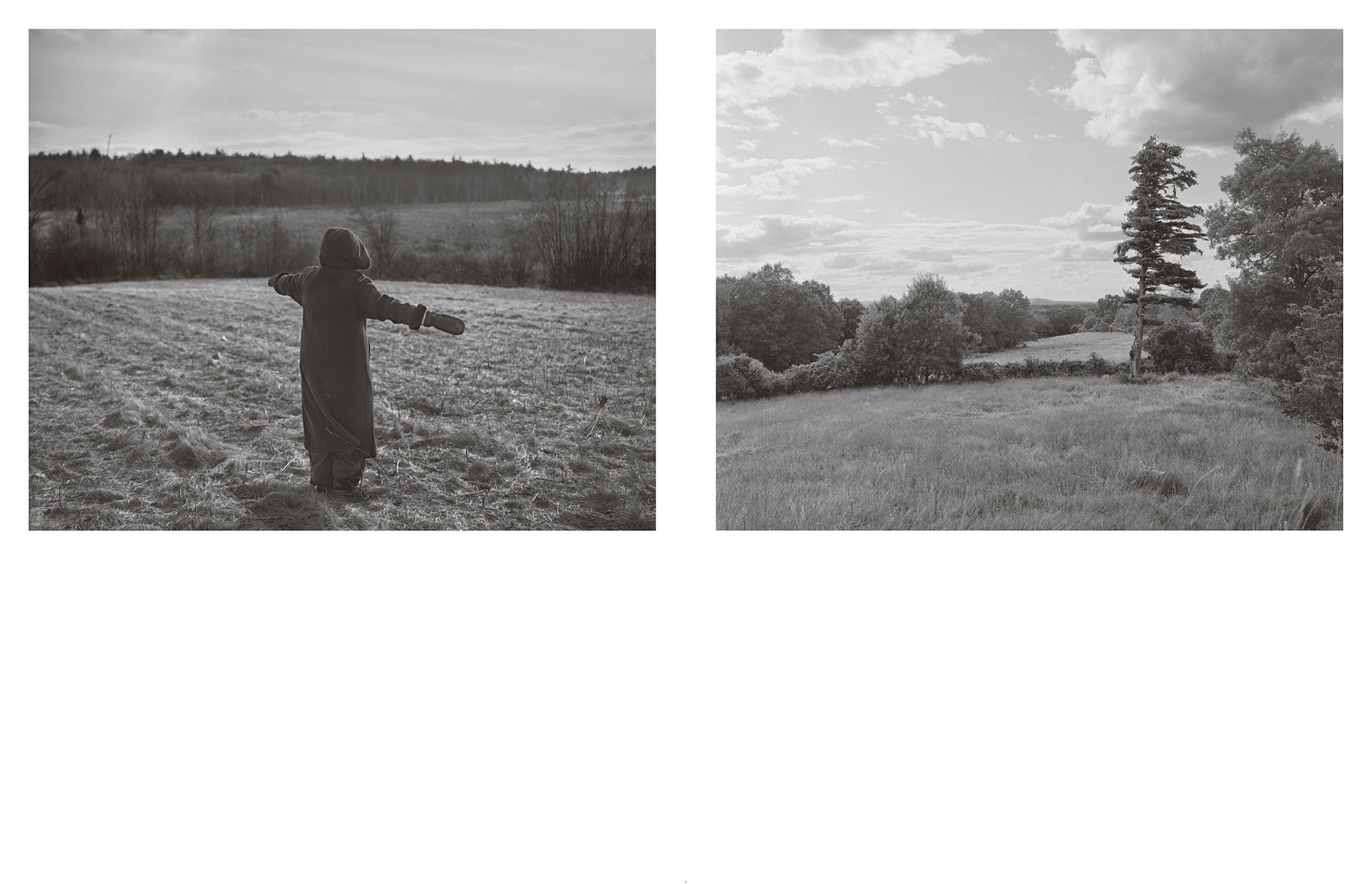

SO: At the beginning, we were just trying to make the most beautiful photographs that we could. Over time, parts of the story began to emerge. We started by taking my cameras out into nature—Grace really loves the New England landscape. She relaxes outdoors in a way that she doesn’t really relax indoors. You can see it in some of the photographs. We also share a love for things like Alice in Wonderland and The Wizard of Oz, and so very quickly, the landscape became a kind of a fairytale with a lot of humor in it.

Grace was approaching 60 at the time which is a normal time when people re-evaluate their lives. She had begun to question a lot of the things that were foundational to her. She was thinking for the first time about ageing, prompted by the recognition that she’d become invisible. I mean, I’m invisible too. Old people are basically invisible, but I think it’s especially noticeable for older women. There’s no one-to-one correspondence between any one photograph and these ideas—the totality of the book conveys this uneasy emotional state.

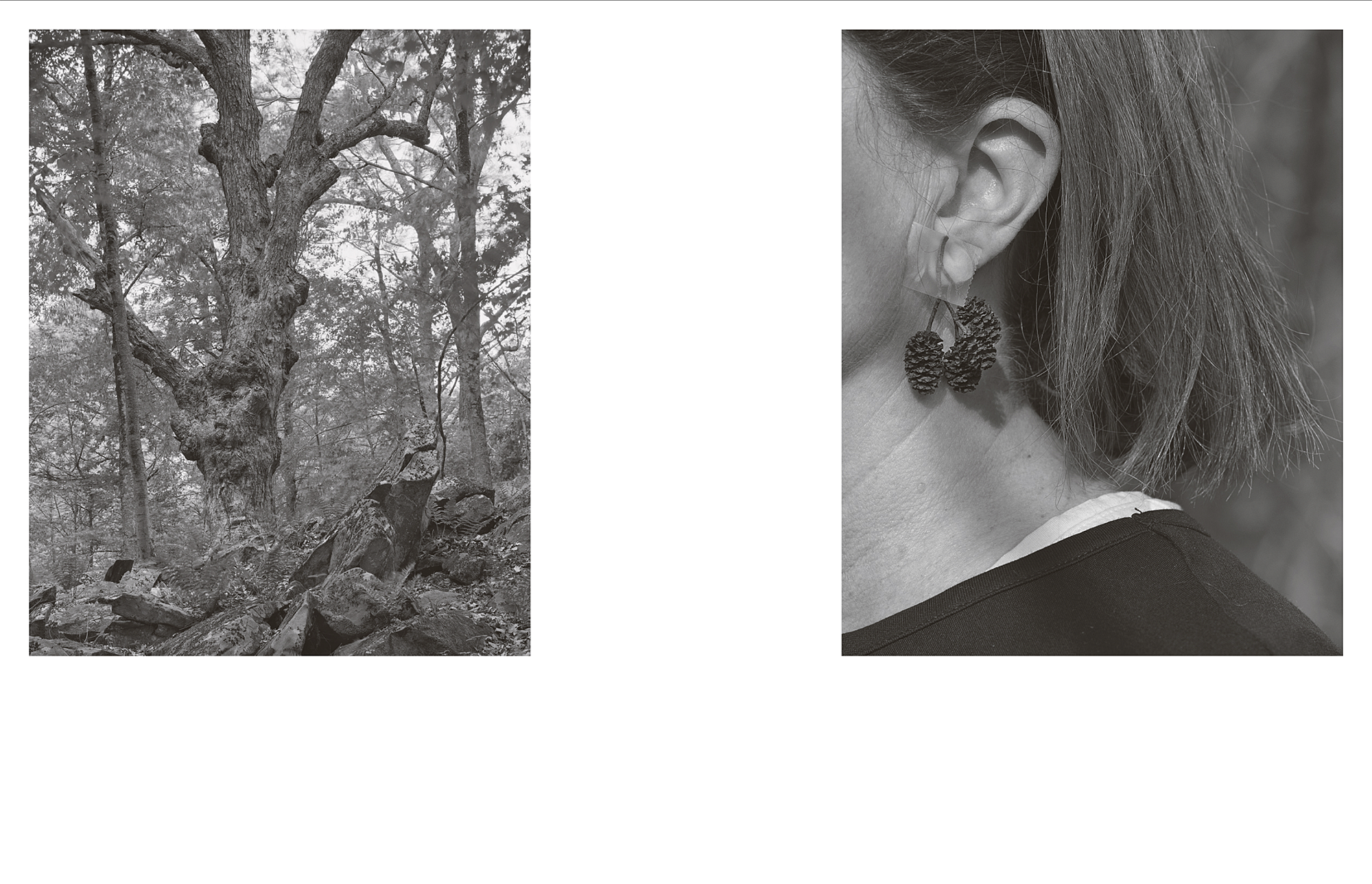

We were also thinking a lot about gender. Grace has never been happy with traditional domestic roles, which in fact, have only been around for about 60 years. In the 19th century, women went out and worked because they had to. This idea that we have of a nuclear family sustained by a stay-at-home wife is just ahistorical and absurd. Grace has always been something of a tomboy; she’s very athletic. She has to use her body—it’s how she manages stress, so that quickly emerged as a subtext of what we were doing and became more and more important to the project.

SW: You mentioned Alice in Wonderland and The Wizard of Oz—you can really feel a sense of play in relation to the landscape. It seems to create a kind of liberation from the constrictions of the themes you’re talking about.

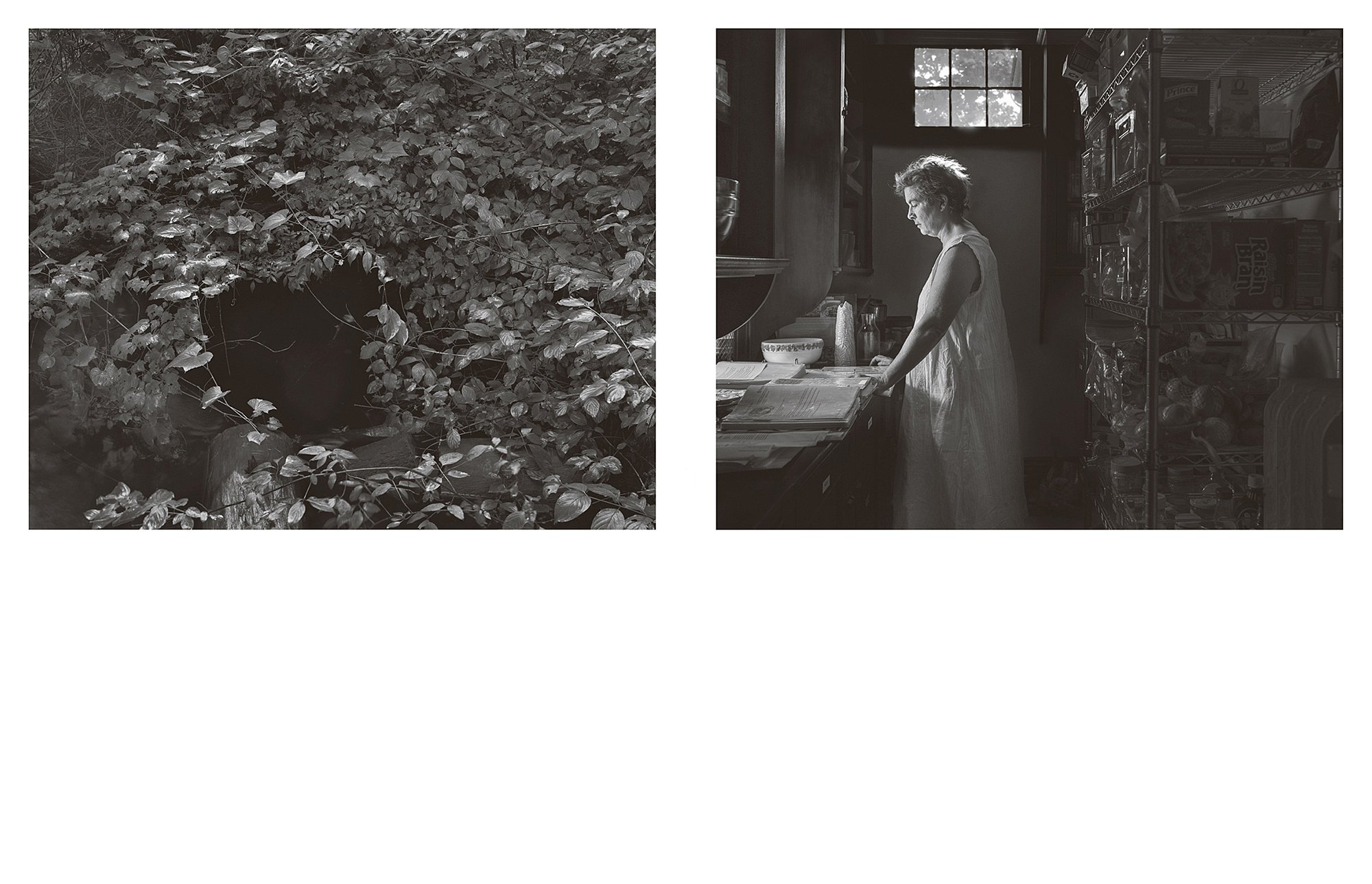

SO: I think the idea of being able to play in the wilderness was a way of expressing that: here I’m free and there I’m not so free. And Grace is just a very fun person, you know. She laughs all the time. I’m actually jealous because when our kids call, she laughs with them hilariously—and I keep thinking, when was the last time we laughed like that? She just loves humor. If you look at some of the domestic images, she doesn’t look that happy.

SW: There’s an interesting quote in the book’s essay that talks about this active man with a camera and passive wife as a muse—a stereotype that you’re concerned with addressing in your work. Is this dynamic something you discussed at any point in the process?

SO: Once I asked Grace if she was my muse and she punched me as hard as she could. There was no ‘muse’ and frankly, I think the best photography of people is collaborative. We also needed collaboration in terms of designing the photographs. They’re all staged, some at the last minute. Very often we would swap who was the captain of the ship and who was the first-mate. At one point, we were arguing over whether we should take a photograph—so we made a rule that everybody’s photographs get made. If I wanted to make one, I was the captain and she was the first-mate and vice versa.

The photograph of Grace sitting under leaves was basically made by her. We were in a park and she saw these leaves that reminded her of Henri Rousseau and his paintings with small people in large vegetation. She decided to sit underneath them—which involved sitting in nettles by the way, so it was a difficult experience. She pulled down her top and said “take the photograph.” I took the one by the rock.

SW: You can really see a different gaze behind it.

SO: That photograph took almost five years to make because of the tide. You can see the line of this seven-foot tide, so we could only take it when the tide was out. But if you want a certain light, you can only take it when the sun is in the right place—so you have to work with two different cycles. Then maybe the weather is bad, or you don’t feel like going out that day. So it took over the course of five years it took to make that photograph.

SW: Was there a lot of organization behind the images you made? Some of the interior shots seem almost like a fleeting moment from daily life but there’s a strong performative element to them, like Grace is playing a character from a film.

SO: The photograph of Grace in the kitchen took about five or six weeks to make too because we had to coordinate light from two different windows and get the hair and background properly lit. She’s in what looks like a happy domestic environment, but if you look at her face, she’s not really that happy. At first we thought this would be a very Americana scene—a beautiful photograph. But there’s this stuff that just sneaks in all the time. She’s looking at a recipe book, which is ironic because she hates cooking, so that’s probably partly why she looks a little bit unhappy. She was playing a persona who is not entirely her but parts of herself are wrapped up in it.

SW: You’ve spent 41 years sharing a life, I imagine this kind of artistic collaboration allows for a new perspective to enter into that familiarity. Did you learn something about each other that you didn’t know before?

SO: I did not realize the depth of what Grace was going through until we made this project. We’re also very strong-willed people—we’re both trying to be top dog in our interactions. I didn’t expect that we could collaborate in this way. With family life, it’s all very quick. You get the food on the table, get the kids to bed, get them out of the bed, get them at the school, go to work. There’s no time to really reflect; you’re working together in doing those jobs but you don’t really realize that it’s a collaboration. It soon became clear that our lives were more collaborative than we realized. And we could have this kind of fun. It was just so fun to make. Our kids were out of the house for the most part and this is what we did, a couple of days a week. For seven years. It’s crazy.

SW: It seems like it was an important space to grapple with questions. Would you say it helped Grace process some of those things that she was dealing with at the beginning?

SO: It’s too bad she can’t answer that question for herself, but I would say she’s a much stronger person. She discovered a lot of things about herself by thinking about what the images mean, how the whole body of work works together. A lot of ideas that she was thinking about really came out and I also learned a lot about her and the things that were bubbling up under the surface. I think we should think about these things more often. Culturally when you reach a decade like 50 or 60 or a milestone, you reflect. But it’s a weird intermittent process—really, you should be thinking all the time. Often we just don’t have the time to take a really deep dive.

SW: It’s a beautiful way to spend time together because it’s a way of playing, it’s a way of merging imaginations and sharing references, which can make new pockets of experience within a long relationship.

SO: Play was really important. Life gets very busy over time and you don’t play as much as you do when you first meet. It reminded me of how much I like to act and play with Grace. It’s been great. I was in financial markets for 32 years and it can be creative but you’re very much moving in one direction. You have an investment process and that’s your process. It changes over time, but not that much. With this, things were just changing all the time. The weather’s different, you’re feeling different. Some days we had to drag ourselves out, and on others, we couldn’t wait to get started. And it’s just great to share those things all with another person.

SW: Photography can be a lonely craft.

SO: I’m an identical twin. I don’t know if it matters, but I’ve never really been alone, right from the moment of conception. And I like working with other people. I don’t always like getting critique; that’s just human nature. But I like working with other people, and I enjoy doing this with Grace.