The intertwined issues of aesthetics, truth, and ethics play out again and again in the medium of photography, especially in the photojournalistic genre. Two recent books about Afghanistan bring this long-running debate to the fore. A pair of American photojournalists, Steve McCurry and Paula Bronstein, are no strangers to the war-torn country, and their new books are the result of repeated visits to a place that most of us know only from news items grimly announcing yet more deaths of both civilians and soldiers.

McCurry and Bronstein, working independently of one another, have dared to go where many photojournalists would not tread and stayed there for longer than others. Their resulting work is deeply felt, aesthetically compelling yet also contentious. Ultimately, both photographers raise important questions about documenting a country that has become a byword for division and disruption.

Afghanistan’s fracturing is topographic, climatic, ethnic, tribal, religious and political—all compounded by foreign military invasions (on the American side, it is the country’s longest war) and the added pressure of involvement from the Islamic State/Daesh in recent years. McCurry’s Afghanistan and Paula Bronstein’s Afghanistan: Between Hope and Fear provoke an investigation of a complicated question: is photography capable of representing the ongoing complexity in Afghanistan, and if so, with what degree of objectivity?

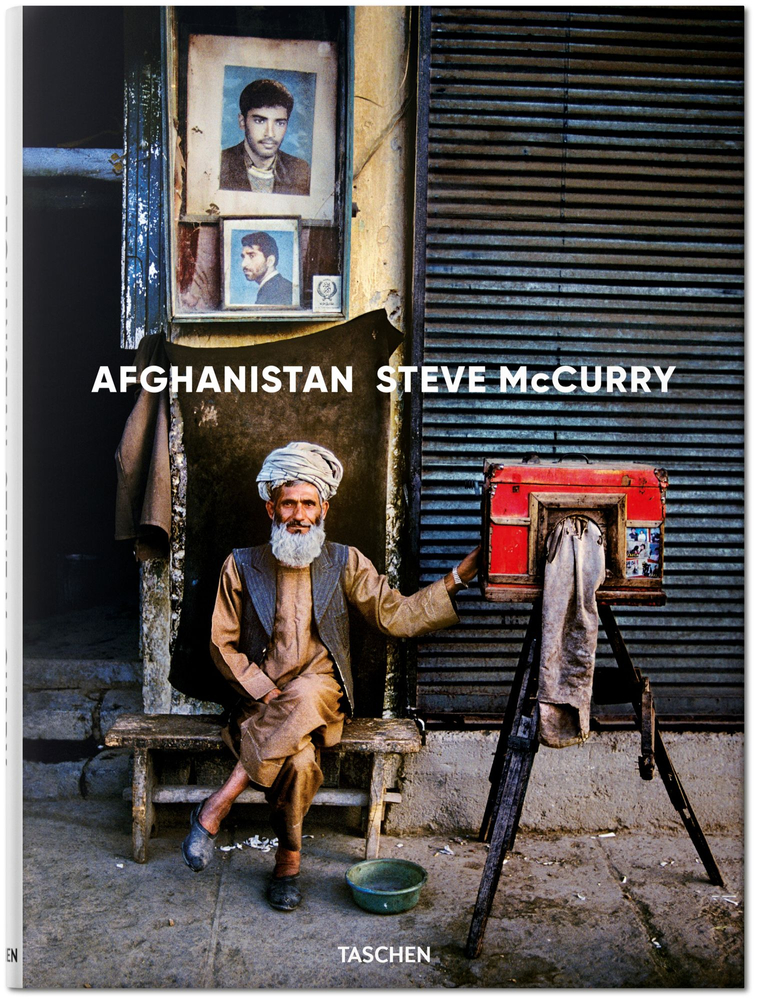

Steve McCurry’s photographs are arresting—they seize the eye and detain your gaze—and the opulent, oversized (26.7 x 37cm) book from Taschen, a 256-page retrospective of his photos taken in Afghanistan, makes this abundantly clear. What is less evident, once the viewer is released and allowed to reflect, is what makes McCurry’s images in Afghanistan so compelling. After all, viewed from a cooler distance, the collection of images is a bit too conservative for its own good; a mixture of portraits, landscapes and scenes so balanced in their composition as to appear staged or painted. This, of course, touches on the thorny issue of authenticity; McCurry has been criticized for digitally manipulating several of his iconic images. It also brings into play the broader, knottier question that any work in Afghanistan is forced to confront: how does a photographer truthfully (if that’s possible) and convincingly record such a charged subject as contemporary Afghanistan?

A characteristic of McCurry’s work and an undoubted strength of his approach to photographing Afghanistan is his fondness for portraying individuals. But he is particularly drawn to head-and-shoulder shots, a tendency that ties his portrait work to, well, portraits. Visitors to London’s National Portrait Gallery are more likely to be stirred by the famous faces in the frames than by any aesthetic innovation on the part of the artist. Likewise, McCurry’s portrait photos in Afghanistan are consistently formal in manner: faces looking into the camera, direct eye contact, uniform backgrounds, motionlessness.

There is, though, a purity in such focus and concentration, what medieval philosopher Duns Scotus called the “this-ness” (haecceitas) of a particular being, and what the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, a great admirer of Scotus, called “instress”: the selfness of a being, a unique quality that makes something meaningful by virtue of its own, unfiltered terms.

Yet this studied formality also governs the composition of McCurry’s portrayals of scenes around the country. His characteristic style, with its careful visual balance of the component parts and an obvious entry-point by way of a human presence, can feel predictable and overly orthodox. For example, the critic Teju Cole, in an article for The New York Times titled “A Too-Perfect Picture,” finds McCurry’s approach formulaic: “The pictures are staged or shot to look as if they were. They are astonishingly boring.” But denigrating the form does not efface the majesty that a finely-executed photograph of this kind is capable of possessing.

To take one example, a photograph of a group of armed men stand atop a mountain in the Hindu Kush: if their weapons were replaced by tripods, they would be intrepid explorers in an inhospitable landscape. Whether Mujahideen or Mason and Dixon, a photograph that captures the human and the geological in such juxtaposition carries its own conviction. The scene works not so much as a depiction of guerilla fighters but as an evocation of human endeavour dwarfed by the impersonal presence of nature.

Returning to the cover image of Afghanistan, taken in Kabul in 1992, we see a photographer sitting on the side of a road with his very old camera on a wooden tripod. This man makes a living on the street by means of his equipment, but at this moment he is posing for his own photograph, this time taken by another professional photographer (McCurry) while sitting on the bench that forms part of his alfresco studio.

This picture of an old-style photographer brings to mind a simile employed by the cultural critic Theodor Adorno. He criticizes the philosopher Edmund Husserl for believing in just one objective reality. Husserl used the notion of “epoché” to describe the bracketing-off of judgements that would interfere with with our direct experiences—in other words, he believed we could deal with the world itself. But Adorno regards this as a way of evading the reality before us: “Like the photographer of old, the phenomenologist wraps himself with the black veil of his epoché,” he writes, and “implores the objects to hold still and unchanging.” For Adorno, what is lost in this supposed distance is the necessity of our personal judgements; an element of subjectivity is always unavoidable.

On the one hand, it could be argued that McCurry’s photographs in Afghanistan are open to the reality of his subject matter and that they remain, like the Afghan whose hand reaches out to make precious contact with his own camera, grounded in the real world. After all, perfect as his pictures may appear, McCurry has visited and travelled across Afghanistan over some four decades. He is not blind to the grim history of the country in which he has explored. Disturbance is not absent from his photos of Afghanistan: the following features are present in his photos: abandoned tanks; a guerrilla fighter resting his Kalashnikov on the plinth of an ancient and priceless Buddha statue in the capital’s National Museum; a prisoner being taken to execution, children armed with belts of ammunition; towns reduced to rubble, bleeding casualties.

On the other hand, Adorno’s simile allows for the possibility that McCurry may be wrapping himself in a cloak of self-censorship by becoming too much a practitioner of the picturesque. Even when McCurry does depict the divisions and devastation of the country, there is a sumptuous loveliness to his photography that arouses critical distrust. A less-than-sanguine young man selling oranges, displayed with the help of a kerosene lamp on a burnt-out vehicle, is undeniable testimony to a war-torn country—but it is also an aesthetically pleasing image that absorbs the viewer in a purely apolitical manner. The question as to whether McCurry’s beauty illuminates or obscures remains open. To me, his pictures’ unbroken radiance appears suspect.

***

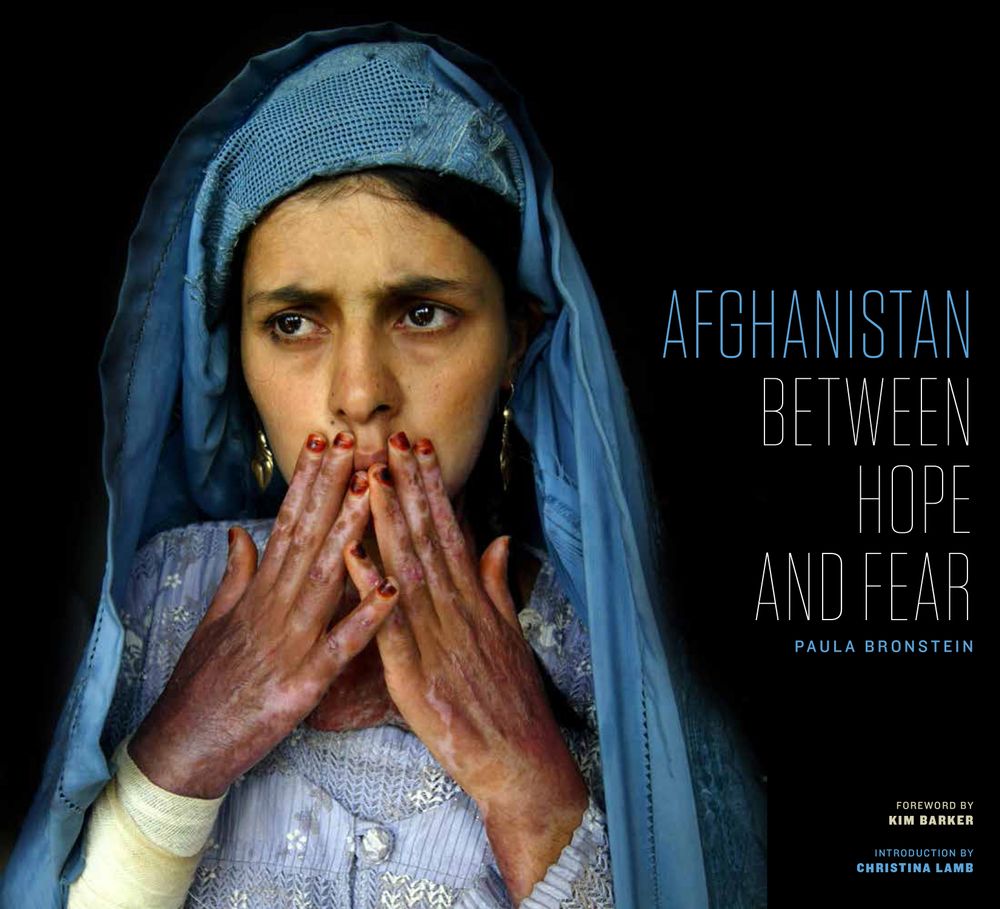

Paula Bronstein is a longtime photojournalist who has worked for the Chicago Tribune and, more recently, for the New York Times. Her photographs of Afghanistan are very different than McCurry’s. The subject matter has a discernible human-interest appeal; she looks head-on at the suffering of Afghans.

One of the sections of her book, “The Casualties,” is filled with photos that are visceral, intrusive and shocking, a catalogue of pain and suffering; it includes close-up shots of dreadfully scarred bodies and desperate women who chose to immolate themselves rather than go on living. In the next section, “The Reality,” the viewer sees heroin addicts injecting themselves inside the abandoned Russian Cultural Center (the Soviets invaded the country in 1979). These photographs of appalling human suffering—including one image of a mother at the bedside of her son dying from malnutrition — are necessary, if horrible, truths about Afghanistan that are not to be evaded.

Bronstein’s book is especially powerful in depicting the lives of women and children, supported by the inclusion of “Afghan Women,” an essay by Christina Lamb. The anguish that is captured in many of the pictures bears out Lamb’s citing of Afghanistan by an international rights group as “one of the world’s worst places to be a woman.”

Photographs like these indicate that Bronstein is doing the opposite of bracketing off reality. Far from wrapping herself in the veil of her own consciousness, she unflinchingly confronts the unattractive reality before her and challenges any viewer who might not wish to acknowledge such unpalatable facts.

As with McCurry, though, creeping doubts can undermine all that I find undoubtedly positive about the work. Bronstein’s book has a coffee-table feel that seems inappropriate to the subject matter and, given that she does engage with political and military aspects, the section called “The Situation” is disappointing: specifically, a naïve political awareness shines out like the glossy paper on which the images appear. Politicos, whose corrupt periods of rule are very much part of the problem, appear with bland descriptions and are photographed with no sense of irony. Women are shown voting with a caption describing “a major step in the effort to restore the country to democracy and stability after Taliban rule.” Admirable moments, yet it is hard to believe that the foreign invasions that have unleashed such carnage on the country and installed governments of their liking have accomplished much in the way of democracy. We see a wounded Afghan soldier being helped from a Blackhawk helicopter, after being rescued in an air mission—a moment of successful cooperation. Yet there is only one photograph indicating an awareness of American responsibility for the slaughter and bloodshed occasioned by their invasion of the country.

Other photographs deal with the base metal of everyday life—miners from the Karkar coal mine showering after a day’s work that earns them four dollars; a girl looking through the frosted window of a restaurant hoping to get leftovers—and they possess a truth value that takes us beyond lovely landscapes or stunning sunsets. Like McCurry, however, their compositions are so elegant that one cannot help but wonder if the form of such photographs best suits the grief and pain that defines much of the Afghan experience.

Returning to Adorno’s image of someone wrapped in a black cloak before pressing the camera’s shutter release suggests that the photographer may be self-deceived by thinking their picture captures a fixed reality. Aesthetic considerations—the desire to make a good-looking image—may blur complexities that then become obscured, rather than illuminated. McCurry and Bronstein are to be applauded for the visual strength of their photographs, but this very strength raises thorny issues about representing a truth as multifaceted as the “true” state of Afghanistan.

As I said at the start, this debate is not limited to the present moment. George Rodger, one of the founders of Magnum Photos, photographed military campaigns in World War II. His final assignment brought him to the Belsen concentration camp after its liberation in 1945. It was a traumatic experience that changed his life: “When I look at the horror of Belsen and think only of a nice photographic composition, I knew something had happened to me, and it had to stop.” The kind of incongruity he faced, in his case pitting the photojournalist’s craft against his humanist revulsion, is an issue for any representation of suffering. This does not except the bold, beautiful—and problematic—work that both Steve McCurry and Paula Bronstein made in Afghanistan and present in these two books.

—Sean Sheehan

Steve McCurry: Afghanistan is available from Taschen.

Afghanistan: Between Hope and Fear has been published by University of Texas Press.

Sean Sheehan is a freelance writer and the author of Jack’s World, with photographs by Danny Gralton and Ciaran Watson.