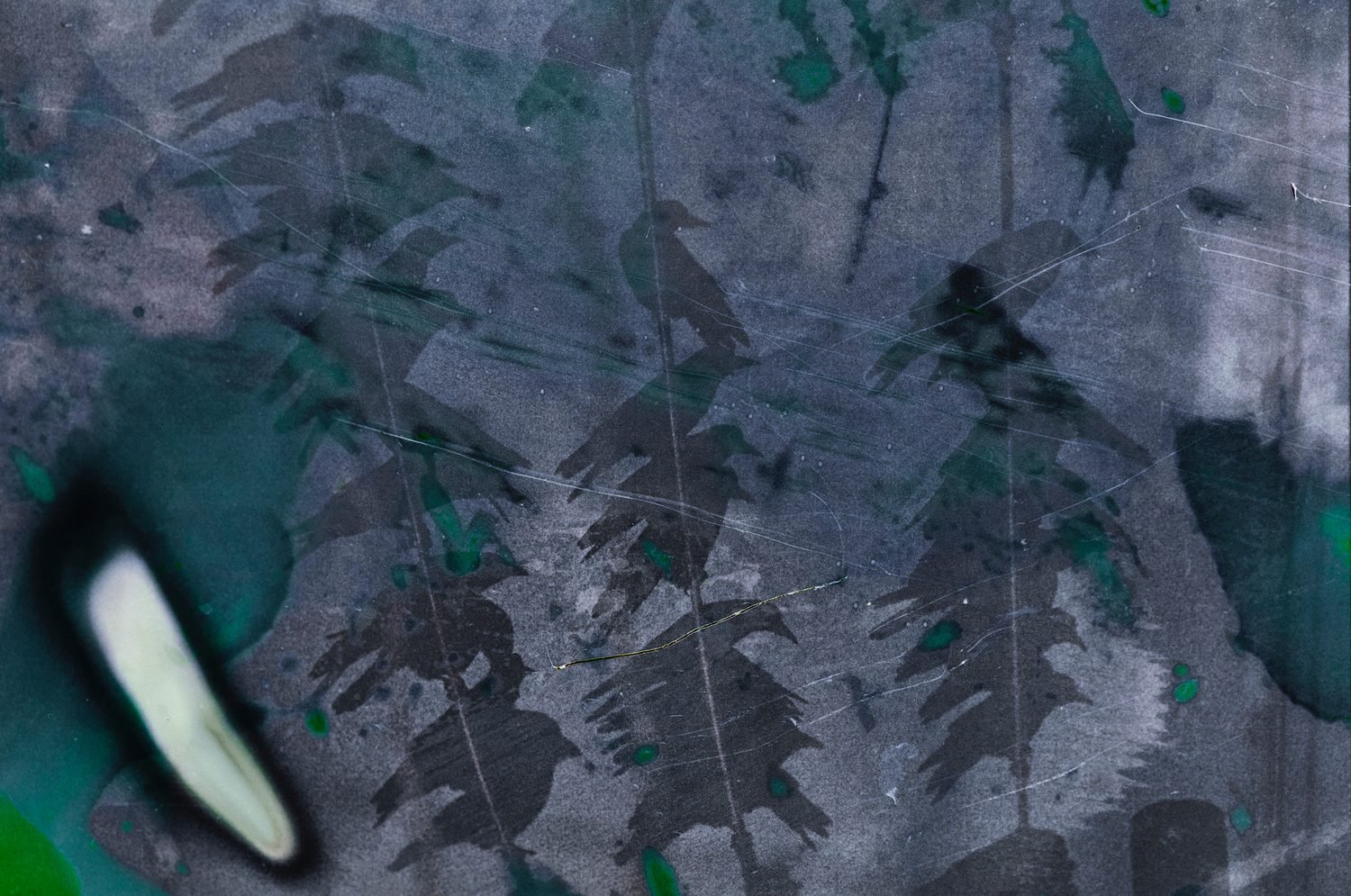

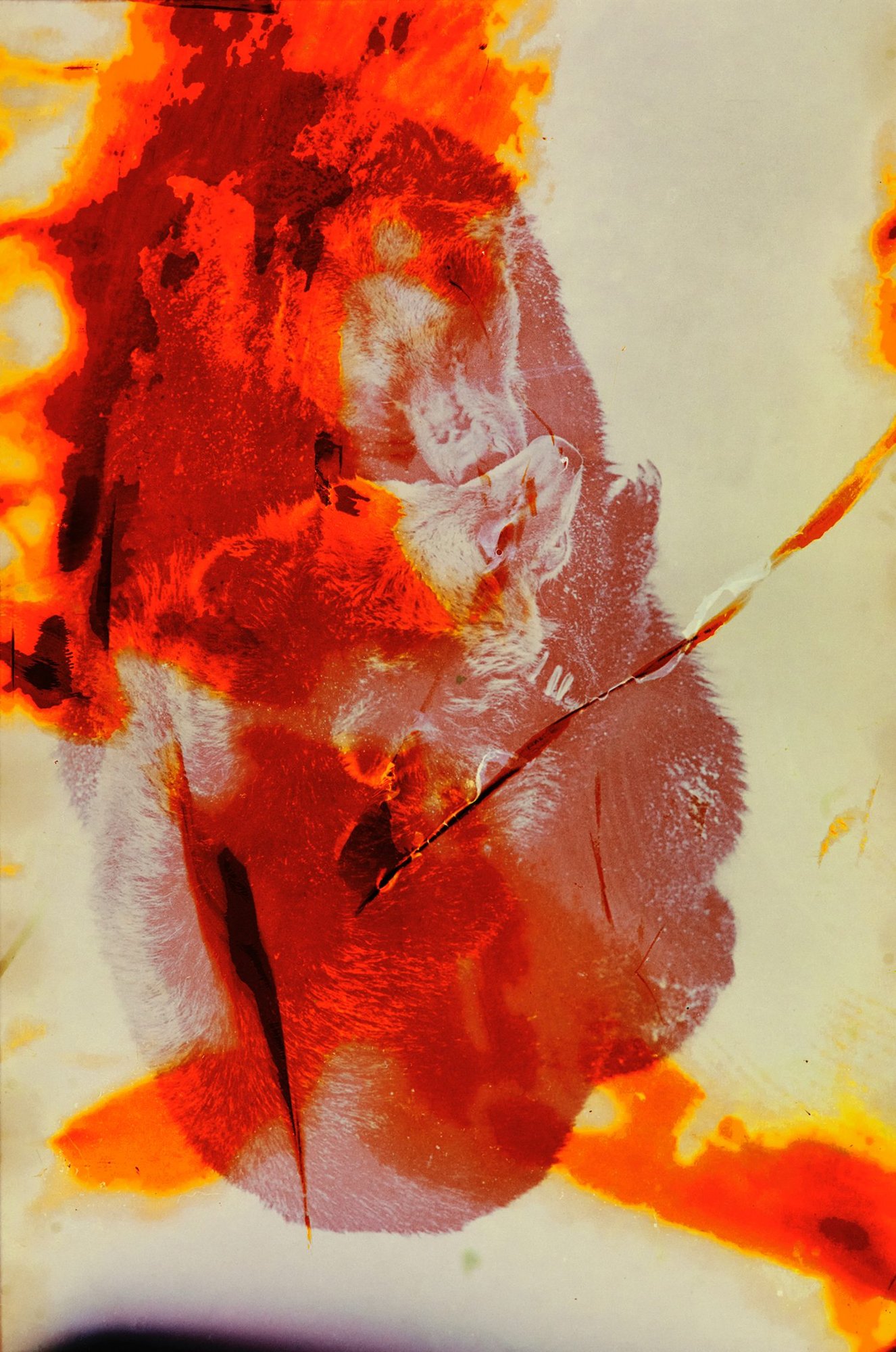

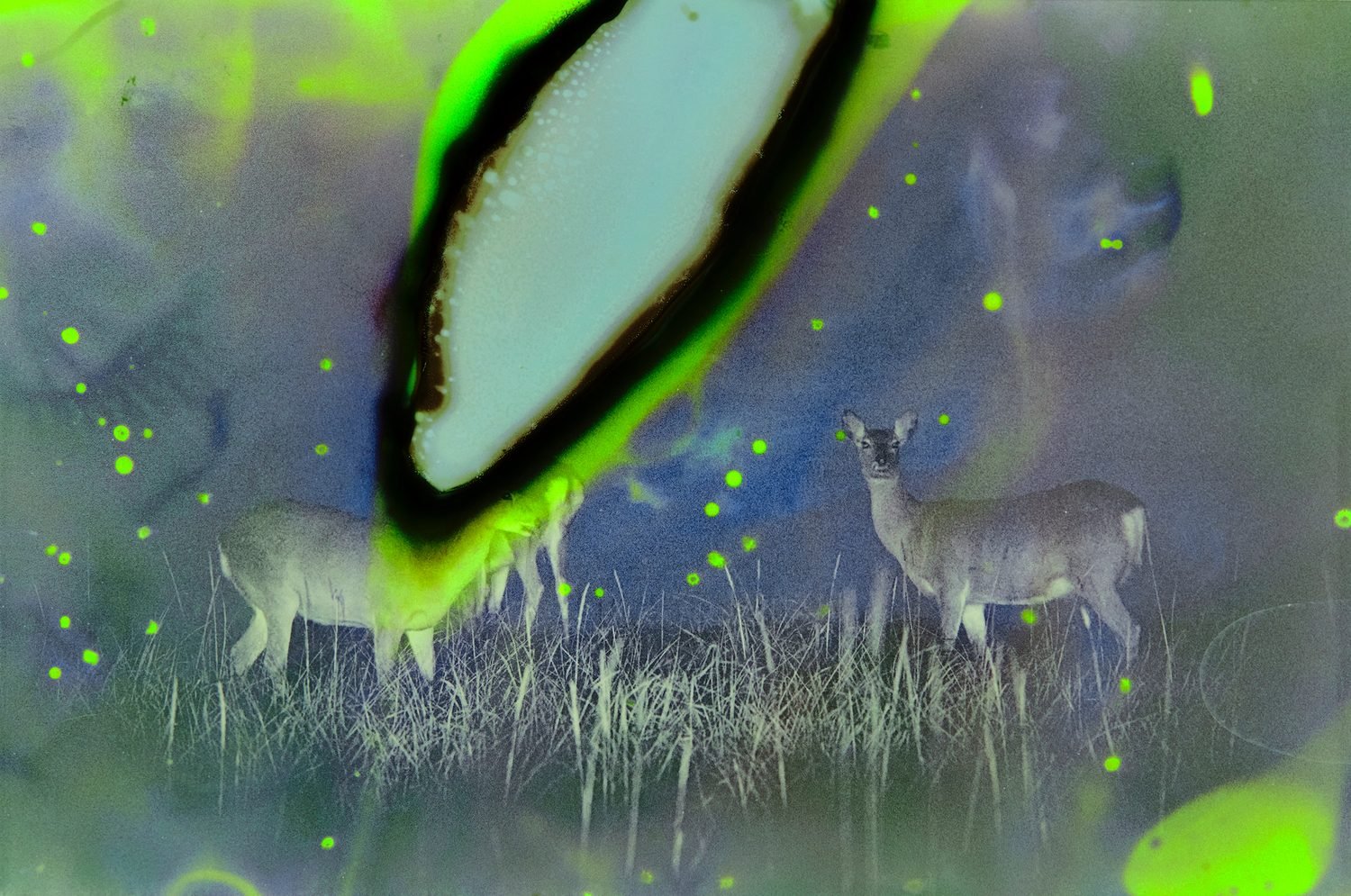

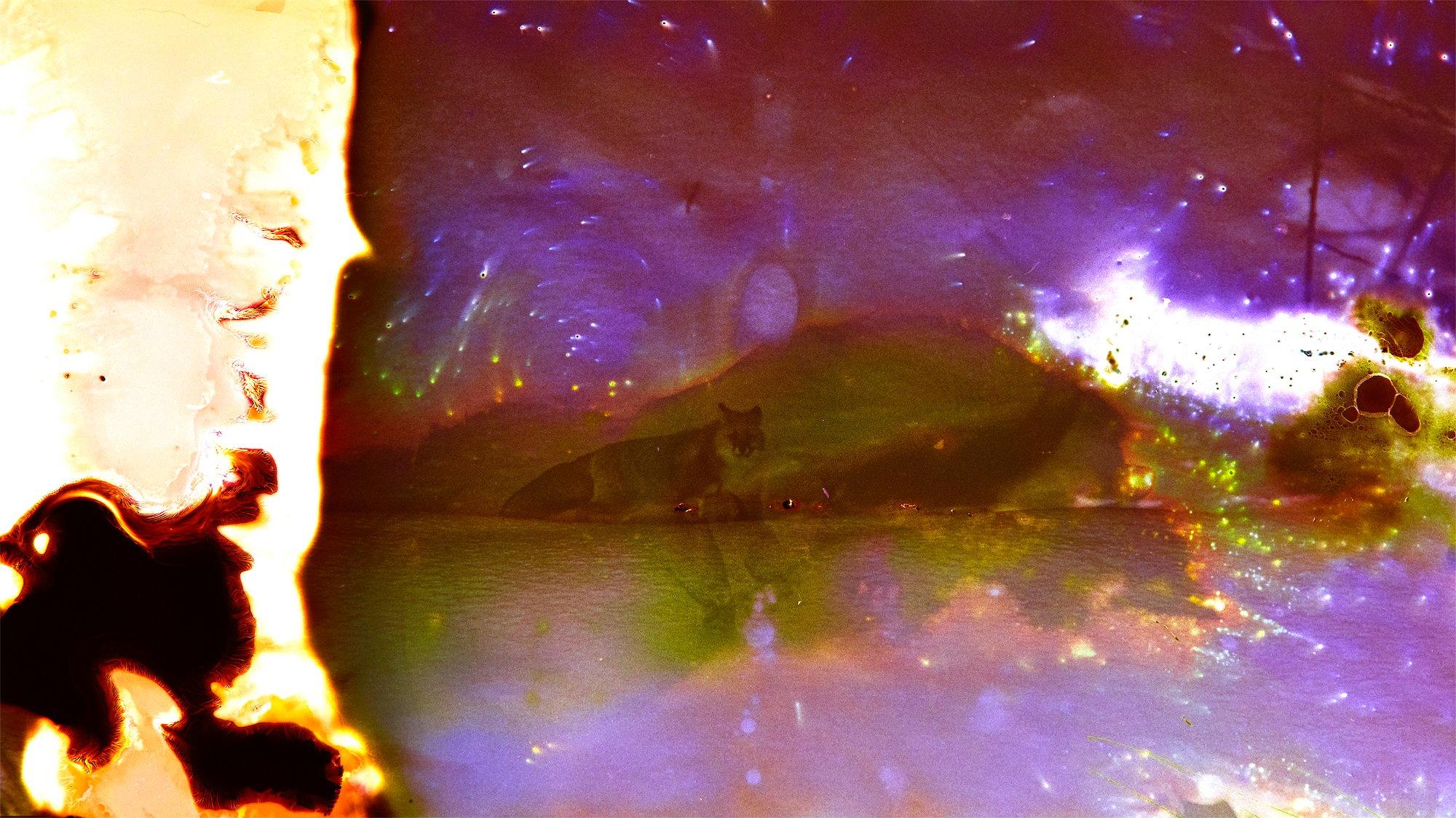

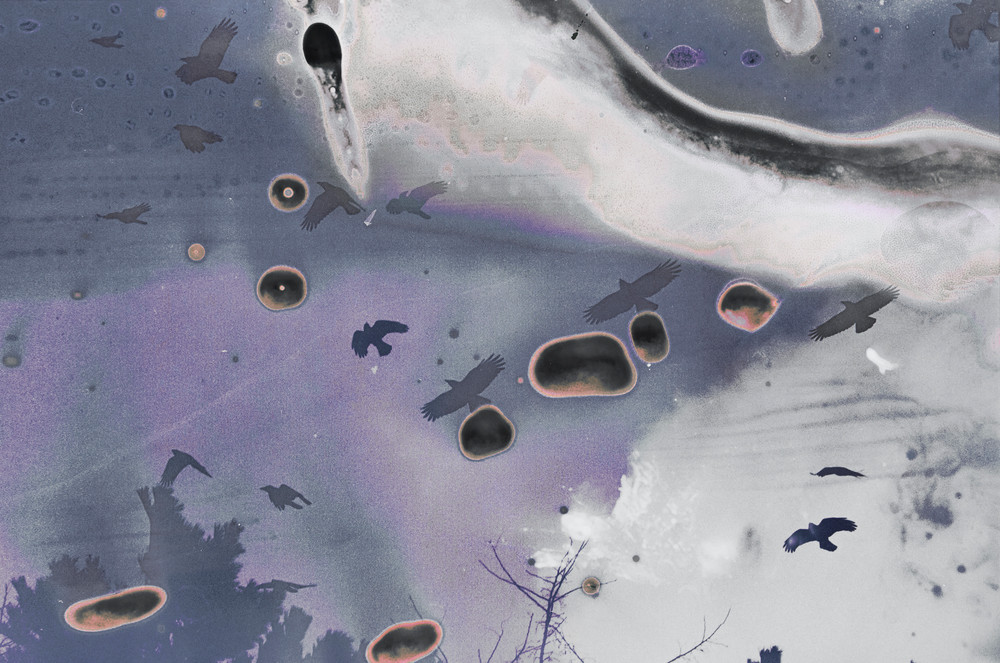

At first glance, Tamaki Yoshida’s images could be interpreted as an abstract expression of a fight to save our planet. Created using chemical disruptions orchestrated in the darkroom, they depict landscapes where deep reds burst like flames, and piercing whites swallow life on the land. Ravens soar through swirling lavender skies, while deer roam martian landscapes lit up in electric blue. They are vivid and otherworldly, yet the photographer insists that they are not abstract.

“It’s interesting that my images are considered abstract, because I have no intention to present them that way,” says Yoshida. The Tokyo-based photographer never set out to capture the animals in her images through a surreal lens. In fact, she never intended to photograph them at all. The photographs were shot back in 2019, during a visit to her mother’s hometown in rural Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost island. Born and raised in the southern city of Kobe, Yoshida was stunned by Hokkaido’s abundant nature and wildlife. “I was completely free from assignments,” says Yoshida, who works day-to-day as a commercial photographer in the beauty and fashion industries. “I was able to see the land and the wildlife with a pure curiosity—not through the eyes of a photographer, but as a first-time visitor.”

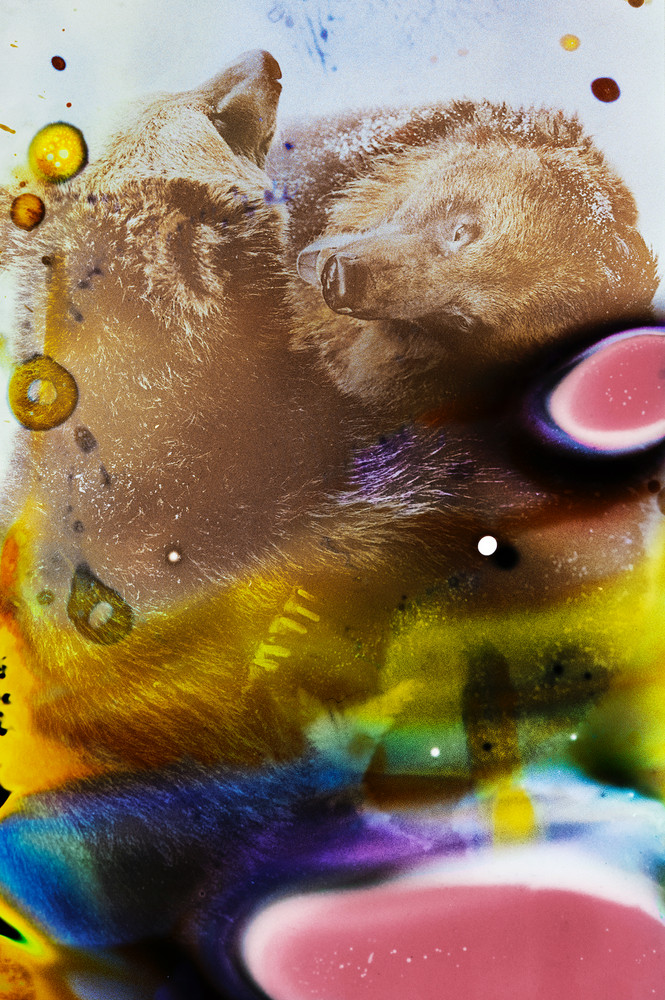

Hokkaido is the only place brown bears live in Japan. It is also home to the Ezo red fox, the Sika deer, and the nation’s iconic red-crowned cranes. These animals thrive in the region’s national parks, which surround its cities and towns. Yoshida was deeply moved by how closely humanity and nature coexist. “Right next to human dwellings was a small pool of spring water where salamanders lay their eggs… Wild herbs were growing everywhere, and there were snails and insects I’d never seen before,” she describes. Yoshida had never photographed wildlife before, but she decided to take her camera out in an attempt to capture “the beauty of the animals and the abundance of nature.”

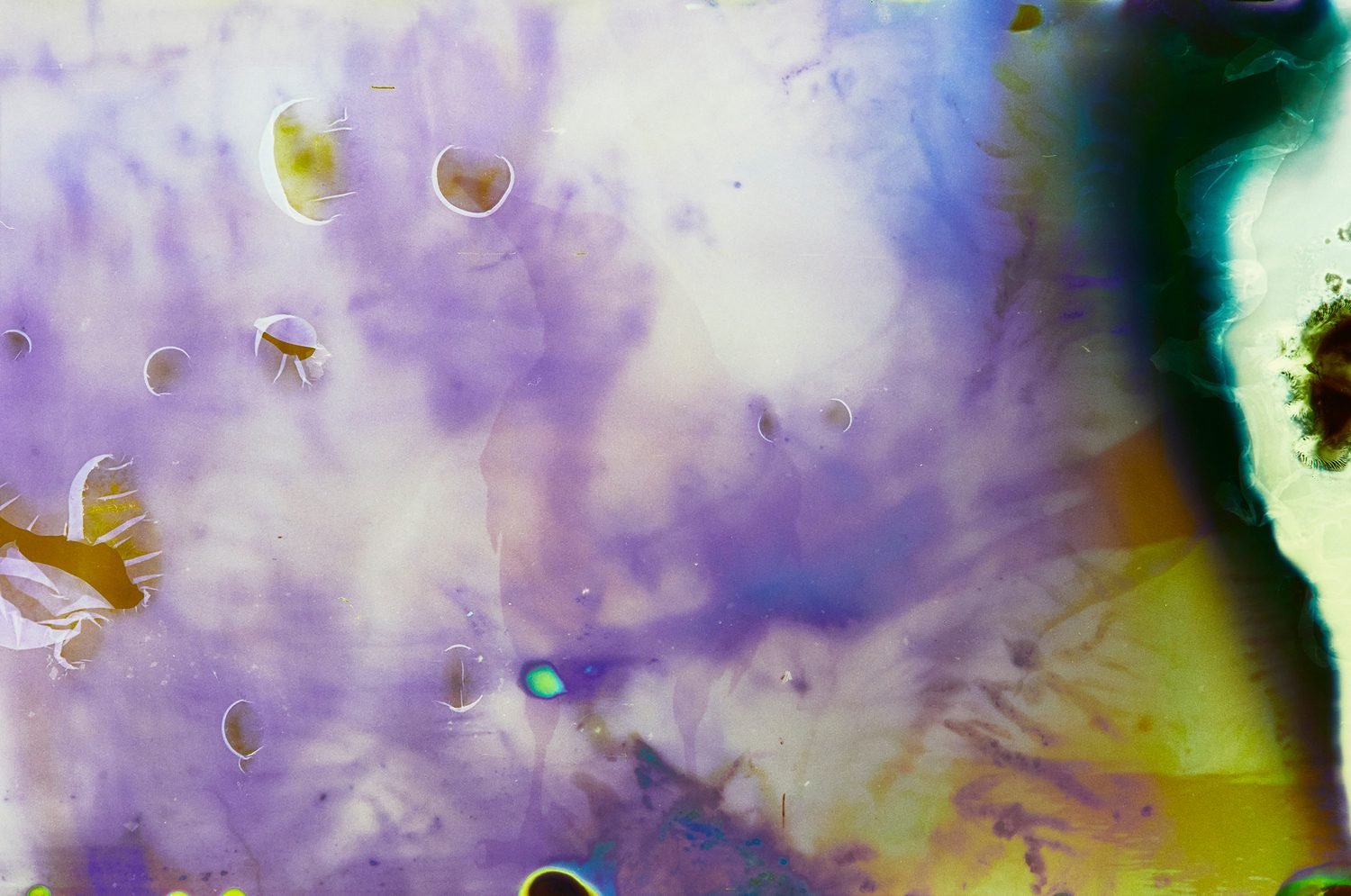

Back in Tokyo, daily life resumed, and these rolls of film remained untouched. Around a year later Covid-19 hit, and with so much spare time on her hands, Yoshida finally decided to develop the film. To her initial disappointment, the images didn’t turn out how she had imagined. A mistake in the darkroom had caused a fog to grow across one of her images. “It was like this huge blur was threatening to erode the deer and its environment,” says Yoshida.

This mistake became the inspiration for Negative Ecology. At the time, Yoshida had been researching the environmental impact of domestic wastewater and had become concerned about the pollution caused by the chemicals we run down the drain, such as detergent and shampoo. “After visiting Hokkaido, I began to experience stronger doubts, and a growing sense of guilt about our daily actions and its impact on biodiversity,” she says.

These damaged images seemed like a perfect expression of the impact we unknowingly cause on the environment. Yoshida proceeded to experiment with the rest of her Hokkaido film using a random assortment of products she uses in her daily life. This included toothpaste, deodorant, makeup, cough syrup, bleach, and even cooking oil and soy sauce.

Yoshida is aware that the resulting work is often interpreted with an activist message, but that is not her intention. “My project is not about showing hurt animals, nor is it about spreading messages,” she says. She explains that, in Japan, all of the animals in her images are classified as pests. In recent years, a booming population of deer, wild boar, and bears have been destroying Hokkaido’s crops and orchards. These animals are often exterminated to curtail agricultural destruction.

But in Yoshida’s eyes, these animals have adapted, survived and multiplied through mass extinctions. When humanity eventually dies, what is likely to remain? “I see this project as a portrait, not an abstract work, that celebrates the strong wildlife that will survive and thrive on earth, even after we’re wiped out,” she explains. If this work encourages viewers to be more mindful of the environment, then that is a positive outcome. But if it inspires a more imaginative way of thinking about the future of the planet, as experienced by the wildlife that will inherit it, then its impact may ring even further and louder.

Editor’s note: Negative Ecology is on show at Tojo Photo Lab in Tokyo until Sunday, October 29, 2023.