Alan Adler—probably the most photographed person in Australia (though he couldn’t care less about it)—owned and maintained a series of photo booths across Melbourne for 50 odd years. Every week, he would undertake testing and servicing on each photo booth across his network. Once an anonymous figure, Adler is now in the limelight due to a book and an upcoming exhibition on his life’s work.

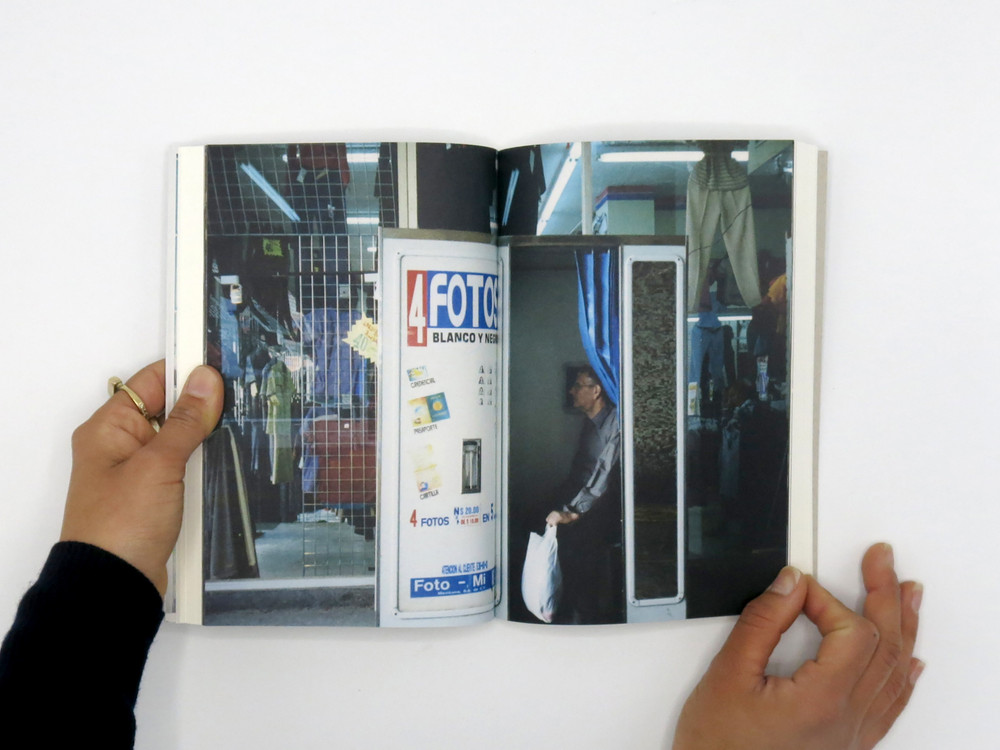

In 2018, Mr. Adler received an eviction notice for his precious photo booth at Flinders Street Station, the city’s busiest commuter stop where the device had done its duty for 44 years. Moved by Adler’s public outcry, Melbourne couple Christopher Sutherland and Jessie Norman initiated the platform Metro-Auto-Photo and campaigned to save the Flinders Street Station photo booth from destruction.

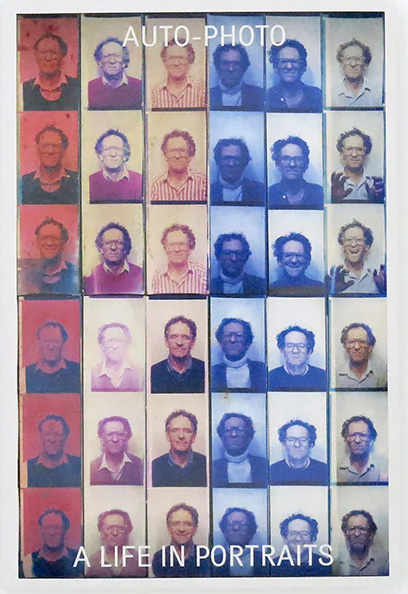

After overwhelming support from the public, the authorities decided to keep the booth at the station. This course of action led to a wider interest in Adler’s rich life story—he lived to be 92-years-old, he bought his first photo booth at the age of 40—which has in turn resulted in the publication of Auto-Photo: A Life in Portraits: a wonderful commemoration of his life’s achievement in book format that includes the many quirky ‘selfies’ he has made over the years as operator of these mechanical-camera machines.

Co-published by Perimeter Editions and the Centre for Contemporary Photography and launched ahead of a major exhibition in 2025, Auto-Photo: A Life in Portraits ”is an ode to a man who, by sustaining the production of photobooth images, actively lives through them.” Thanks to the editors, who also smartly included some illustrations of the mechanism of the booth, Adler’s private collection affirms a valuable attribution to both the Australian vernacular history and our collective archive of ‘useful photography.’ In fact, let’s consider it as a situationist art piece on its own merits.

What is it about these machines? How can we understand their great appeal? For one, the mass popularity of the matter-of-fact mechanical nonchalance, that results in the idiosyncratic aesthetic of these kinds of images, comes from a different motivation to the selfies we create in the digital age.

As the Canadian-born American sociologist, social psychologist, and writer, Erving Goffman famously addressed in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1956), when an individual comes in contact with other people, they will attempt to control or guide the impression that others might make of them by changing or fixing their setting, appearance, and manner. This impulse—as addressed by Goffman long before the digital selfie emerged, let alone the Japanese ‘purikura’ photo booth and culture of ‘kawaii,’which reflect an obsession with beautifying self-representation, originating in the Japanese video game arcade industry—is not a common use of the more ‘old school’ photo booth.

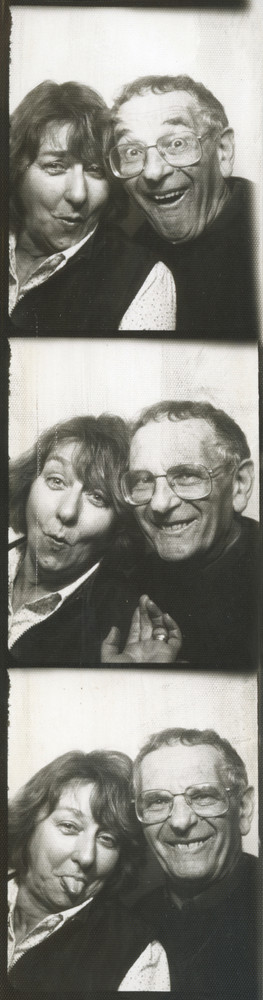

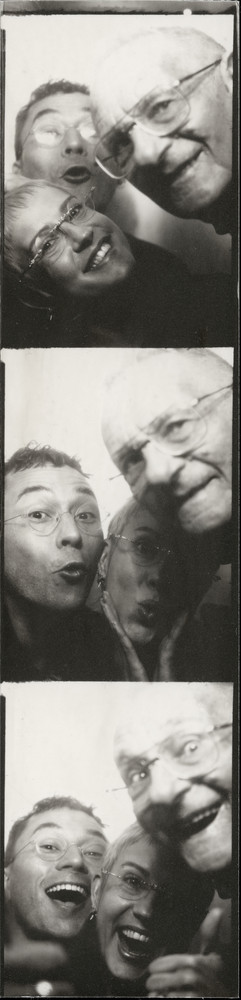

These hyper-contemporary aspects of the selfie-by-booth would require another lengthy article—perhaps for another time. Here, the point to be made is that impression management typical for the Insta-selfies of our age starkly contrasts with the more intimate ‘backstage’ phenomenon of the photo booth selfie, where people never felt deterred from making quirky gestures, and committing all sorts of ‘lewd acts’—exclusively for themselves.

This concept clearly rises to the surface in Auto-Photo: A Life in Portraits. As Mark Bloch aptly states in an extensive blog on the history of the photo booth, “there is something uniquely magical and completely spontaneous that happens behind the curtains in these simultaneously most private and most public of art-making locales.” But the book also brings to the attention how the mass interest in having a strip of images snapped in such stations led to an increase of entrepreneurs that would come to exploit these machines. Alan Adler belonged to this group, who made it his business to manage a set of photo booths scattered around the city of Melbourne from the early 1970s onwards.

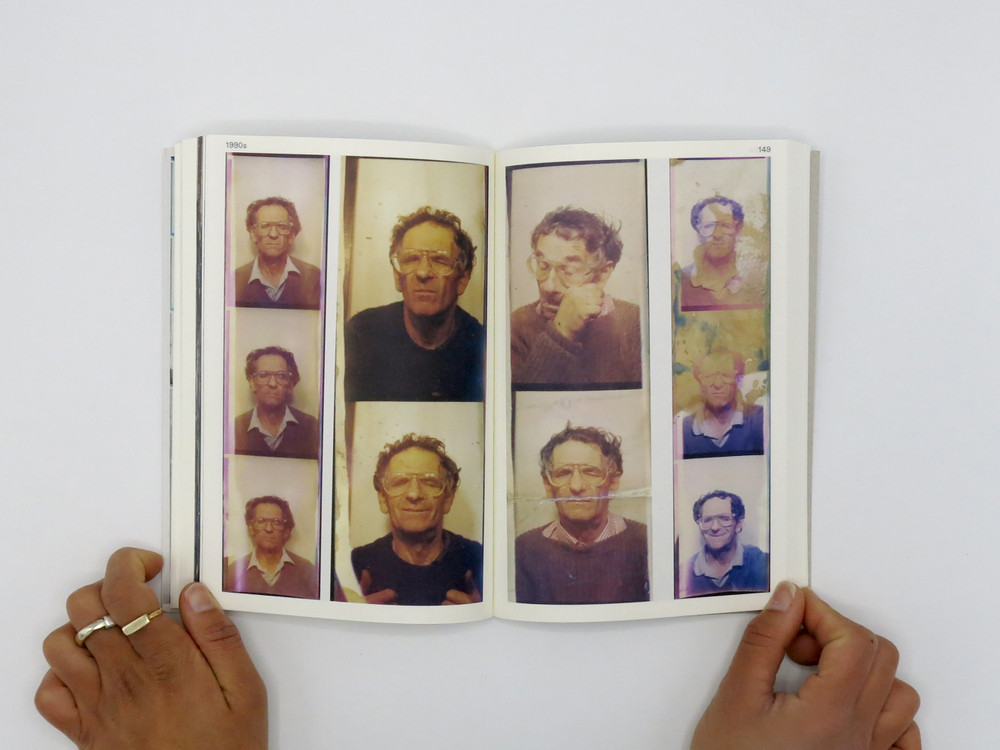

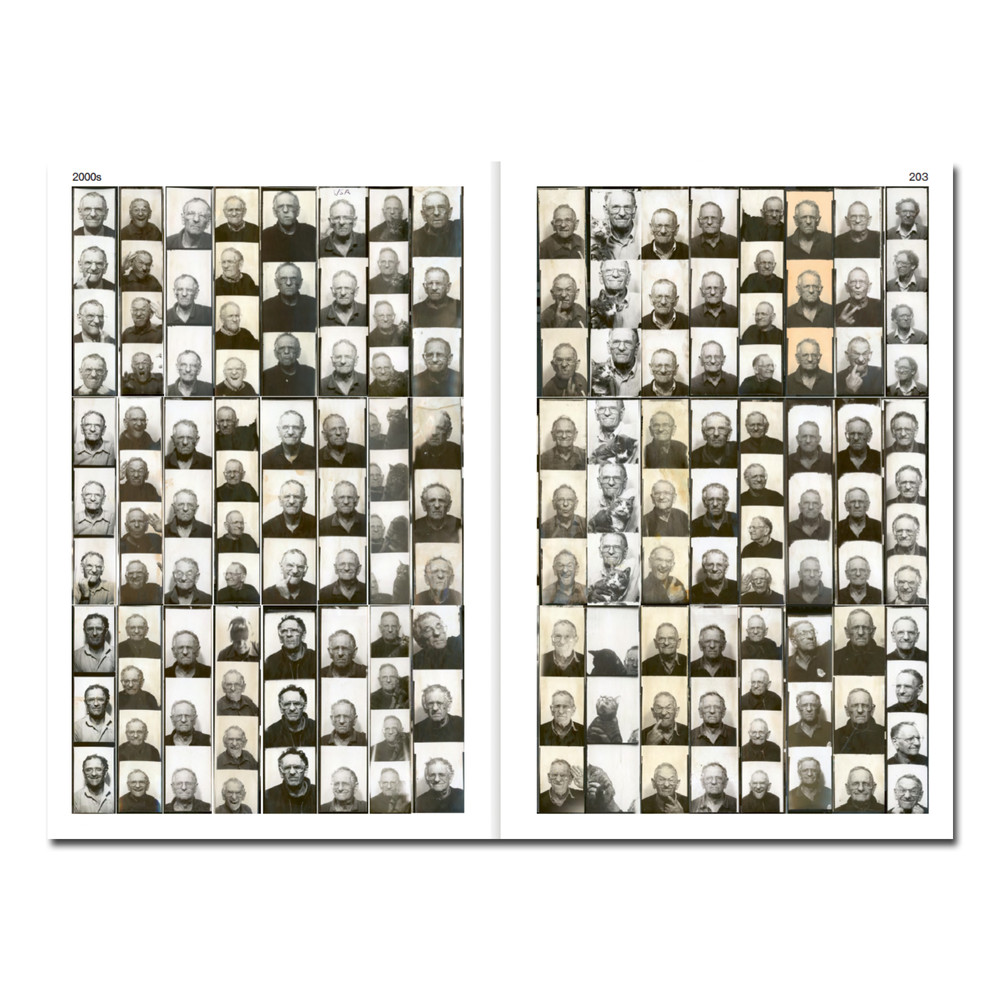

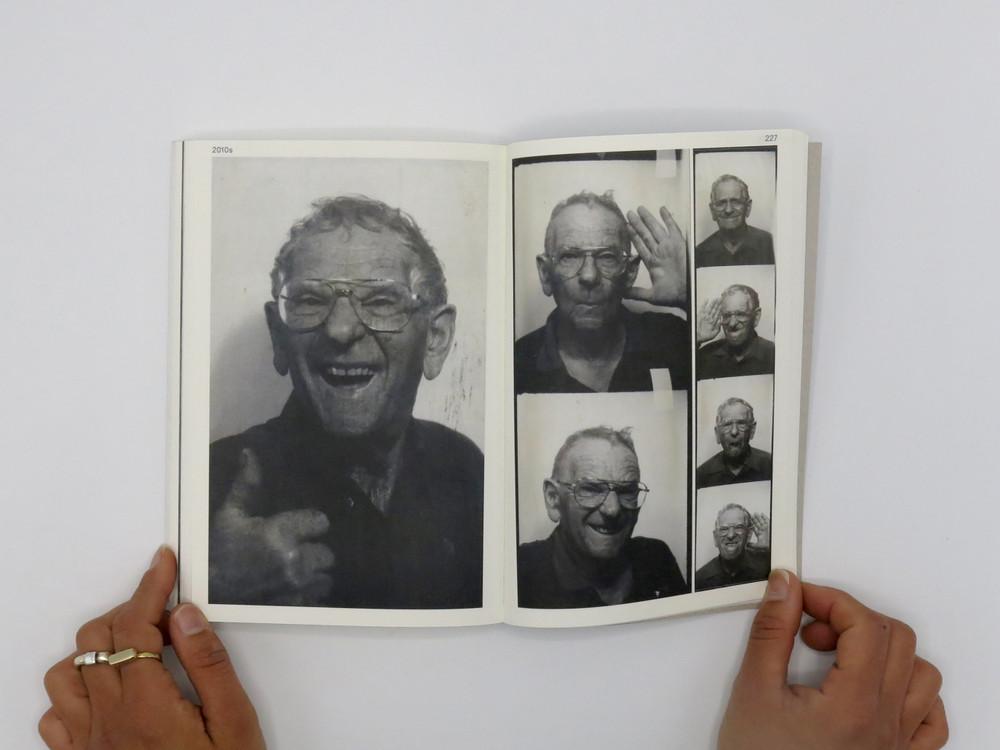

A motor mechanic by trade, Mr. Adler was already 40-years-old when he bought his first photo booth. At some point, he owned 16 machines. Twice a week, he would make his rounds to replace the paper and the chemicals and collect the coins that had been amassed. As part of this routine, to ensure that the focus, flash, and print quality were all up to standard at the end of each service, he’d take a seat in the booth and produce a test strip of photographs. Analog images in black and white, three images joined together vertically.

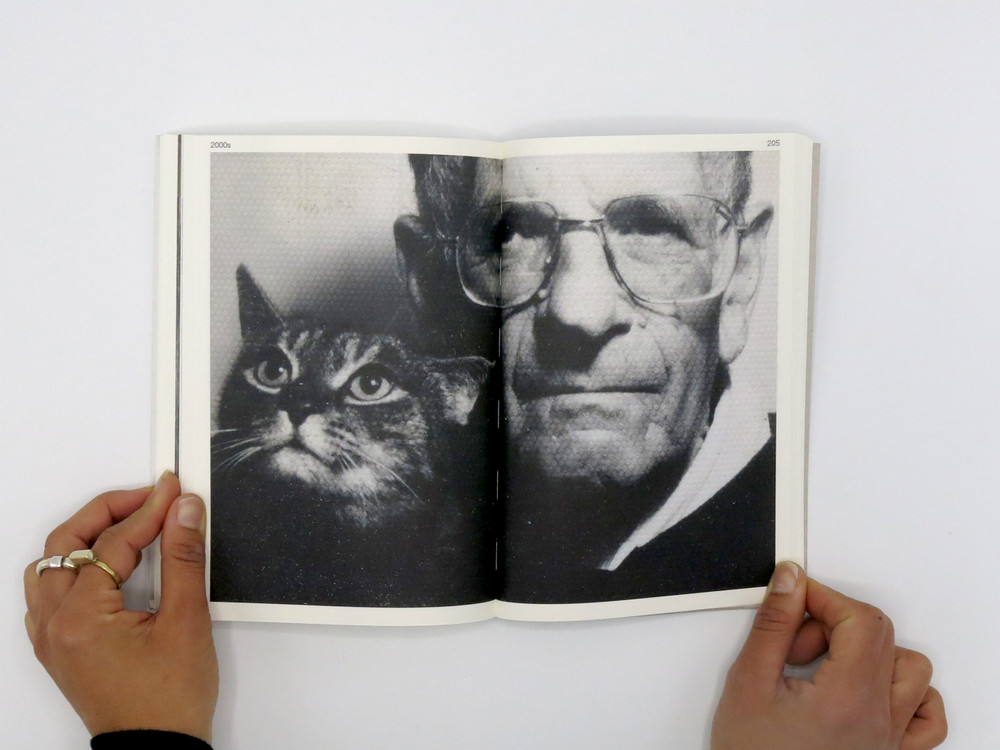

For half a century, Adler has been making these test shots of himself. He often had his eyes closed, or his face contorted into weird grins and outlandish grimaces. Sometimes, when the booth was in his own garage for repair, he’d sit with his cat on his lap. The consistency and the repetition of his jolly gesticulations is mesmerizing. For over five decades, he archived thousands upon thousands of peculiar portraits of himself—a selection of which makes for the core of this wonderful and insightful new publication.

Do his standardized booth-strips resemble similar kinds of actions by artists who, throughout the 20th century, have been playfully involved with the automated machine-image? It seems not. More likely, it’s rather a matter of the medium defining the circumstances. That is, the very design and concept of the photo booth itself can be assumed to be the probable trigger of such habitual quirkiness.

Let’s recall that Mr. Adler was a mechanic and his act of making this many test strips was, above all, a pragmatic action. However, as seen in Auto-Photo: A Life in Portraits, the consistent act of doing so has turned this practical routine into an unintended artistic achievement which deserves recognition—both by way of this great book and the retrospective scheduled for 2025. Sadly Adler passed away on Dec 18, 2024. Thanks to Chris and Jessie from Metro-Auto-Photo, he was guest of honour at the launch of the book in Melbourne in October, and was able to see and feel the love and admiration of the community he served for 50 years.