In 2007, the Oxford Junior Dictionary had started to replace nature-related words such as ‘acorn’ and ‘heather’ with words such as ‘broadband’ and ‘chatroom’—an alarming discovery Camille Lemoine made after working on her project Down Tower Road. This small but significant loss reveals a lot about our times, where our attention lies and the kinds of disembodied digital environments in which we spend our days, zoning out as the hours fly by. “This shift scares me; the loss of knowledge risks a loss of meaning,” the photographer reflects.

This kind of loss prompts a burning question: what kind of language might fill this ever-widening gap? And what kind of ‘knowledge’ could invite us to connect to, rather than conquer, our surroundings? “I have been thinking about my work as a way of remembering or preserving this more-than-physical connection we have with the land,” she explains. “As we continue to experience the loss of land and species, it is important that we remember not just what these things look like, but how they made us feel.”

The first time the Scottish photographer picked up a camera was to make a specific image on her fashion design course. Drawn to the way it could be used to express one’s personal, unique experience of life, she constructed her own scene using goose feathers from the garden, blown eggshells and dead branches. These ‘props’—bits and pieces that Lemoine has been collecting since childhood from her garden at home and the moorlands and grazing fields of Baldernock—crop up throughout Down Tower Road, important fragments of her visual vocabulary. To photograph is, in her words, to “be intimate with life.”

Cycling through deep gray skies and misty dawns, the shifting landscapes of Down Tower Road are tinged with an understanding and love that comes from a deep, continual relationship with place. “I felt that rural places in Scotland were often tied to the same narratives within photography, such as country shows, farming or grand vistas,” Lemoine reflects. “These stories definitely have a place, but they didn’t feel reflective of my own experience of everyday life in rural Scotland. I felt an absence of everyday experiences or less tangible moments such as fluctuant weather, the behaviour of light, the repetitiveness of scenery, the subtle changes of season—the things that people living in these places interact with and feel a familiarity to.”

For Lemoine, Baldernock is a deep source of inspiration. “Having grown up there and being where my parents still live, it is the place I know more intimately than anywhere else, and I often feel a strong pull to return,” she explains. “To a passer by, the landscape may not feel particularly notable, but if you know where to look, there is an unruly wildness about the area that I have always loved. The moorland where I took pictures of my friend Charly in amongst the heather has a particularly special energy and is somewhere I always return to during difficult times. It was important to me that the locations I shot in were ones that I had grown alongside over the past 20 years.”

The book takes us out into wide expanses, blooming with that purple heather abandoned by the dictionary, but also inside her family home which Lemoine describes as “indistinguishable” from the wild outdoors. Much like her favourite spots outside that she returns to again and again in search of solace, the interiors of the house are weathered and full of traces of life and activity. “Things like the tear in the sofa, stains on the floor from letting the birds wander in and out from the garden, the unstable staircase my dad made from driftwood, collections of feathers in every room…”

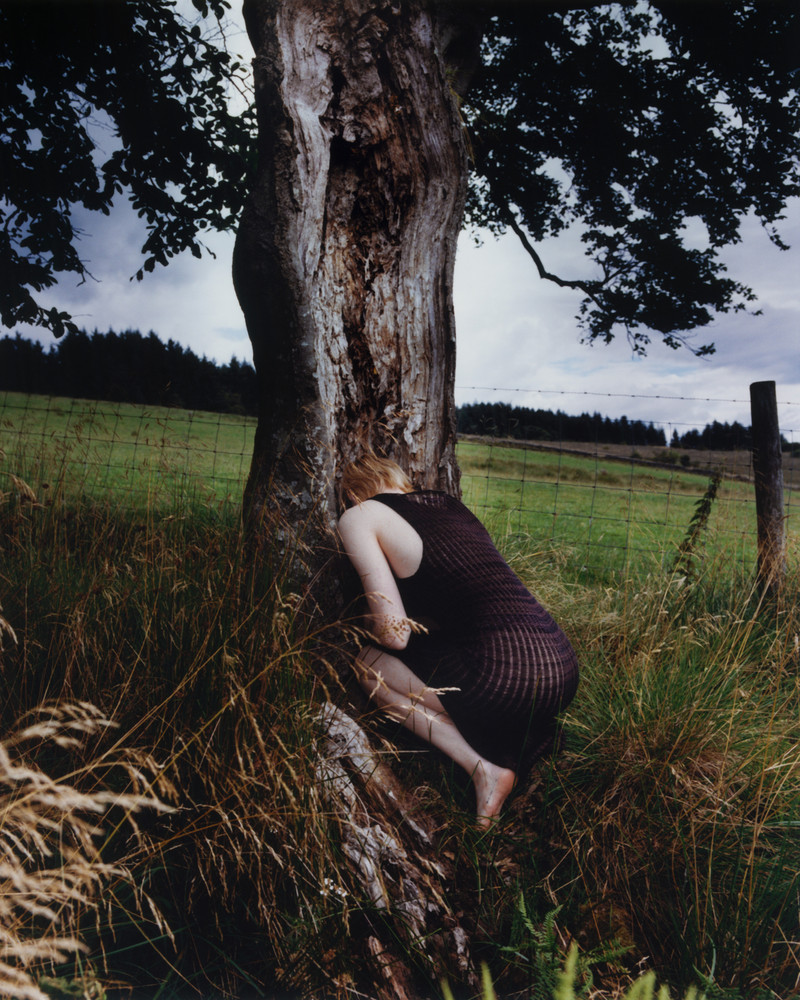

The way Baldernock is observed here is far from the distanced perspective that photography can sometimes fall foul to. There are bodies tumbling through the land, cheeks imprinted with the pattern of long grass, muddy feet. Lemoine uses her camera not to capture or study her surroundings but rather to “meet” it, the project allowed her to seek “new ways of being” in familiar places through a devoted process of looking. Down Tower Road simultaneously preserves the things she has seen over and over again and deepens her relationship with them, inviting her to explore at night and dawn.

“It is a place full of small yet significant moments that give you a sense of belonging, such as the same two families of Canada geese and Grey Lag geese returning to the field next door every year to breed, or knowing which hidden lochan to expect tadpoles in this year,” she ponders. Taking inspiration from female nature writers like Kathleen Jamie, Nan Shepherd and Christine Ritter, intimacy is at the heart of Lemoine’s way of knowing—or rather getting to know—a place. We are not apart: we are embedded within it, we belong, and whatever we think we know is always subject to change. In Nan Shepherd’s The Living Mountain, a contemplative account of walking the Cairngorms, the author writes of her efforts: “It is a journey into Being; for as I penetrate more deeply into the mountain’s life, I penetrate also into my own.”