Though a master of analog processes, Frank Lopez also knows something about surrender. His abstract prints are the outcome of an experimental darkroom practice that requires both planning and accident, order and chaos, control and flow. Drawn to the tactility of working with analog processes—particularly as a response to the alienating effects of technology—Lopez’s approach to photography reaches beyond the material realm. The chemical reactions he is now adept at invoking act as a mirror to his internal world, the marks emerging on the paper a reflection of his own feelings.

An Engaged Buddhist, Lopez uses the darkroom to process and express the important personal and collective issues shaping his life. In Manifestations of Light and Energy, he tends to personal loss, the chemical transformation of expired silver gelatin prints becoming shorthand for the neverending cycle of life, death, the flow of energy into the cosmos, and rebirth. In his most recent body of work, They Tried to Bury Us but They Didn’t Know We are Seeds, the horrific crimes of the current US administration come under scrutiny.

In this interview for LensCulture, Lopez speaks to Sophie Wright about the concept of the Antiquarian Avant-Garde, finding peace in the darkroom and using abstraction as a language of resistance.

Sophie Wright: Can you tell me about your path into photography?

Frank Lopez: I grew up as an auto mechanic, dreaming that one day I would take over the family business. Art was a luxury we couldn’t afford in my household for we were fighting to live the American Dream as we grew up in a middle-class household in economically-challenged far South Dallas. One day my mother pulled over to the side of the road and pulled out a Polaroid camera, creating instant magic. I picked up a camera in high school as an afterthought, got some books on the subject, and learned how to expose and develop my own black and white images. I didn’t know you could make a living at this and after a gap year, found a local college that offered a degree in photography. I have continued learning and working in the business since earning my undergraduate degree in 1990.

SW: How did you first come into contact with the analog processes that you work with? Did you begin with a more ‘straight’ approach to photography?

FL: I became interested in alternative photographic mediums after taking an Alternative Printmaking class in 1989. Combining that with an Abstract and Experimental class led me onto a path of thinking less concretely and more in an expressive medium. Unfortunately, those lessons were hard earned as I became a society wedding photographer in the 90s, largely forgoing my art practice. It was when I picked up a pinhole camera again in 2000 on my first trip to Europe, that I was awakened again to make images for myself.

My images at this time were of landscape and architecture; they were quite straightforward. It wasn’t until I started to see the effect the pinhole camera had on people within the landscape that I started to concentrate on street portraits made using a pinhole camera. From carnies at the State Fair of Texas, to street portraits in China, South Korea, and Vietnam, I became much more interested in the cultural landscape. Over time, I turned more introspective, thinking of how technology was providing a barrier to the human experience and how chemical reactions could be used to express my feelings. It has been a long journey getting to where I am and I hardly recognize the photographer that I started as.

SW: What first attracted you to analog techniques in this hyperspeed age of disposability that we now live in?

FL: I started photographing so long ago that there was no term for ‘analog’—it was all just ‘photography.’ I was a part of the last generation where digital did not figure in my education. I had to pick all that up in extended classes when I was a working professional in the 90s. Looking back at that period, professionals started speaking of more personal projects that used historic techniques: pinhole, toy camera, cross-processing film, distressed Polaroid.

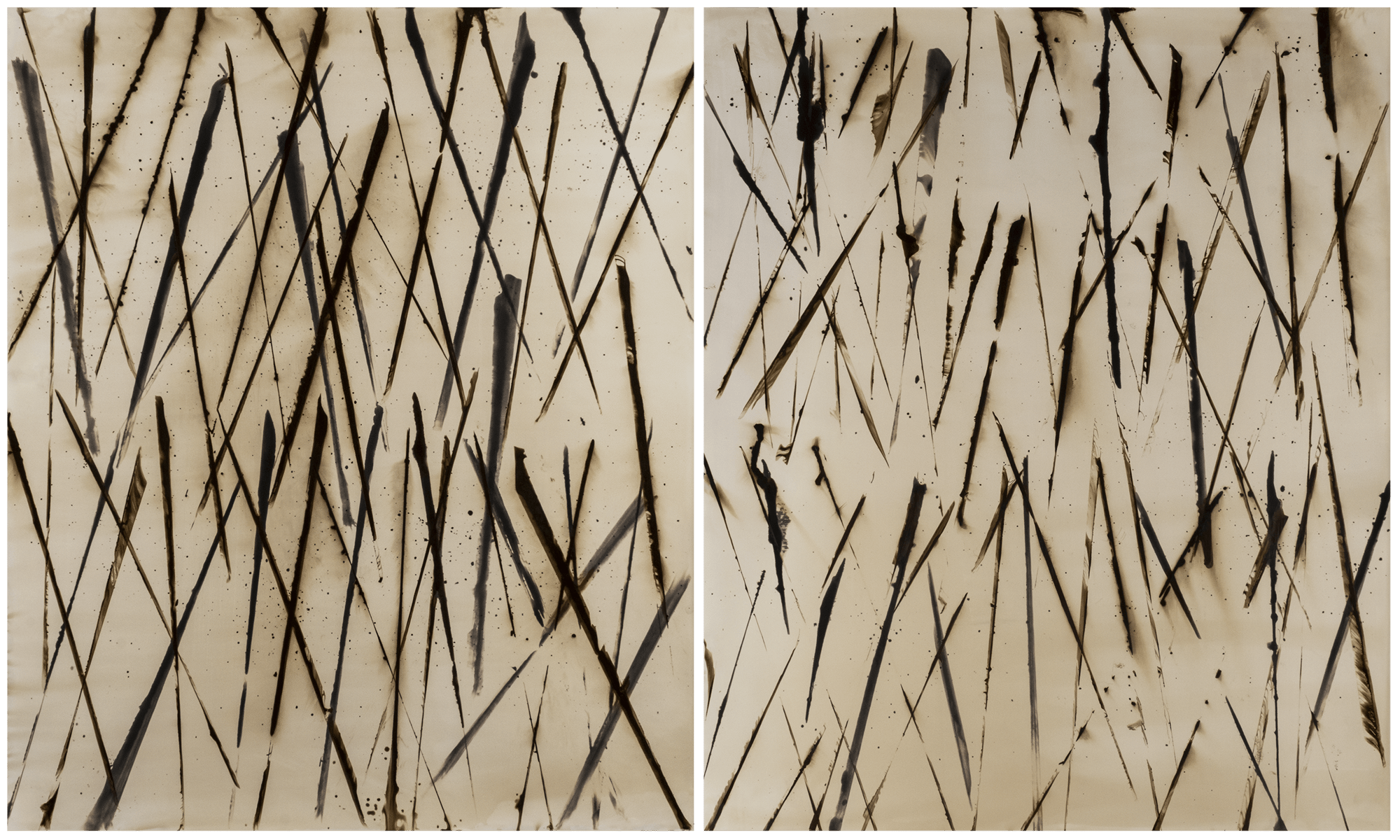

These were all processes that I already had in my tool kit and used them to varying degrees in my photographic practice. I think more deliberately when moving in the analog space—but just because it is analog doesn’t mean that it is good. My current practice sees me writing, sketching, and planning before I head into a darkroom session with a previsualized idea in mind. I work in themes where the process follows the idea and rarely is it the other way around.

SW: You use a wonderful term when discussing your work—‘Antiquarian Avant Garde.’ Can you elaborate a bit on how it speaks to your approach?

FL: The idea of the ‘Antiquarian Avant-Garde’ was first introduced to me by the wonderful critic and art writer, Lyle Rexer. I found one of his articles in the early aughts that was a forward for his book by the same name. I had been well versed in alternative processes by that time (palladium, gum, cyanotype, pinhole) but was largely working very traditionally with those techniques.

It was the application of these techniques to issues-based work that lit a fire underneath me. Here were artists that worked in historic methods (antiquarian) but looking forward to redefining the use of process in new and unexpected ways (avant-garde). It was truly a landmark book for me and highly influential. I reformed my thought process to think of issues, ideas, and concepts that I could grow from, learn, and teach in my future photography program. This did take many years to percolate, but sometimes that is what it takes. To be patient and willing to accept lessons.

SW: Can you tell me about the range of darkroom techniques that you use?

FL: The list of historic and experimental processes that I know and teach are rather lengthy and not restricted to what I show. I was one of the early practitioners in North Texas to learn and teach the Tintype/Ambrotype processes (not the first!) and began in the early aughts.

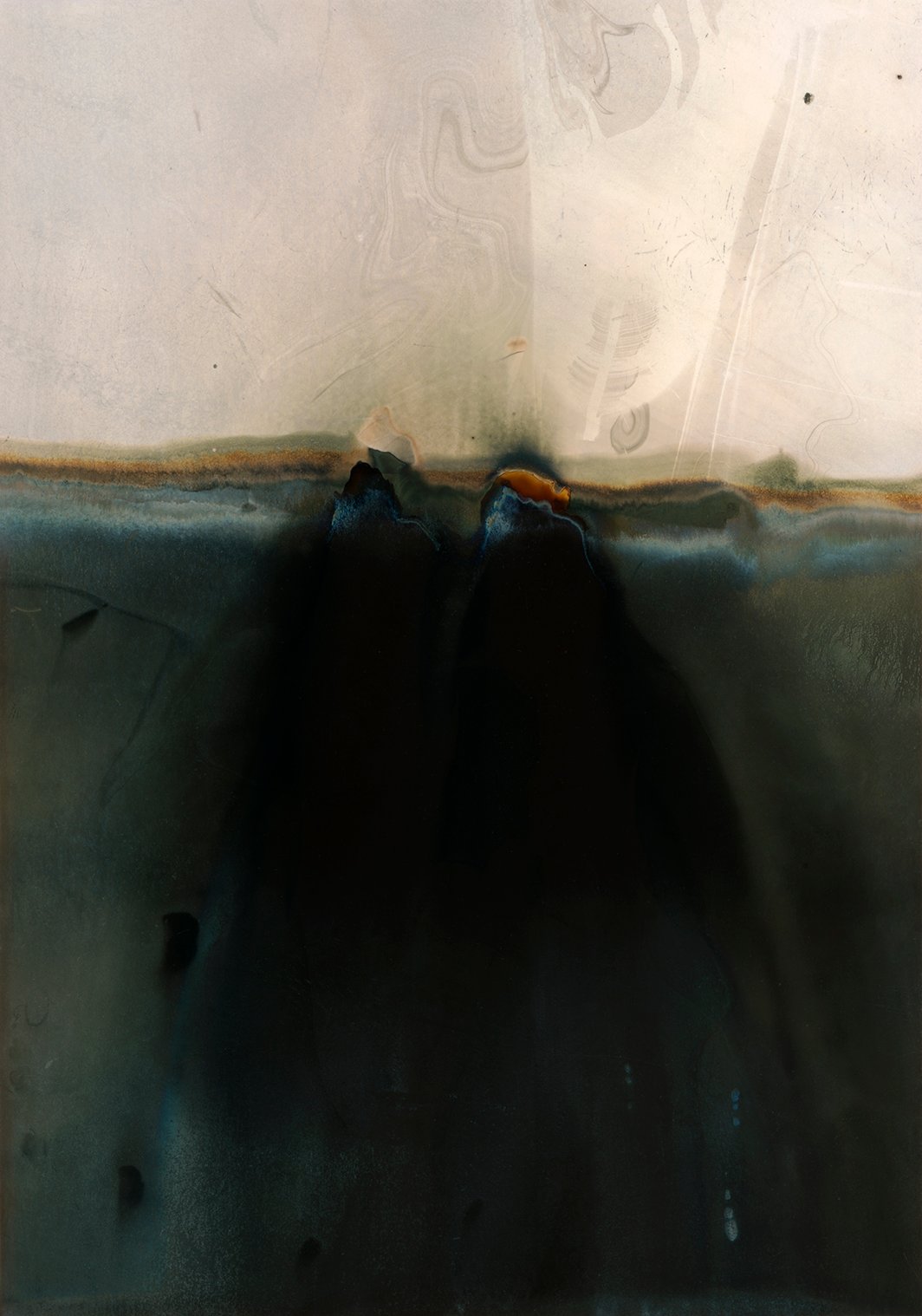

I teach cyanotype, paper transfers, Mordançage, Chromo, Sabattier (and Sabattier masking techniques), manipulated developers for staining and toning, experimental and historic silver gelatin toners, Brownie Hawkeye cameras… you get the idea! I no longer perform wetplate, platinum/palladium/gum prints because of the caustic chemicals. Did I mention Mordançage?! Currently, I am working exclusively in Chromo (previously called Chromoskedasic) with few practitioners. I lift halides to the gelatin silver paper surface to produce a silver-plated appearance and is combined with developers and historic toners. It is my current passion. Ultimately, I’m looking to find a voice through the language of art.

SW: When did Buddhism enter your life and how and how did you find its expression through photography?

FL: In 2007, after many years of trying, I finally visited Vietnam for a three-week trip to photograph and experience a country where two of my uncles had served in the war (the Vietnamese call it the ‘American’ War). I had gone through a divorce and serious car crash in the previous five years, and I needed to find time to rediscover myself. Why had I been spared? Why wasn’t I angrier at the time of life that I found myself in? I had just begun teaching at Greenhill School (this is my 20th year now) and I wanted to experience Southeast Asia. There, I found Buddhism for the first time—the devotion to a way of life, a way of forgiveness, a path to finding inner peace. Seeing the immense dedication, ways of giving to each other, temples, methods of praying and meditation was all too specific to dismiss.

Between 2009 and 2011, I helped run a program in the summers teaching in China and South Korea the ways of using photography as a tool to use for cultural exchange. I was introduced further into the many different aspects of Buddhism. It was after all these experiences that I found my way to be an Engaged Buddhist that stands for morality and social justice. These lessons permeate my daily existence in and out of the classroom.

SW: Do you find a sense of peace in the darkroom?

FL: The darkroom is a place of solitude and resilience. I allow myself to enjoy a meditative experience, regardless of the success of the day. I consider each day in the darkroom a success so long as I learn something. Music and ambiance play an important part of my experiences—I always look forward to sharing my time with Brian Eno, Kikagaku Moyo, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Khruangbin, Max Richter, Mozart, lots of jazz… the list goes on and on. My practice is therapeutic, humbling, enlightening—at times!—but most of all, rewarding as I search for answers for justice and mortality.

SW: You draw parallels between the relationship of the transformation of silver halides that takes place in the darkroom and the flow of energy that feeds into Samsara. Can you talk about the symbolism that underpins Manifestation of Light and Energy?

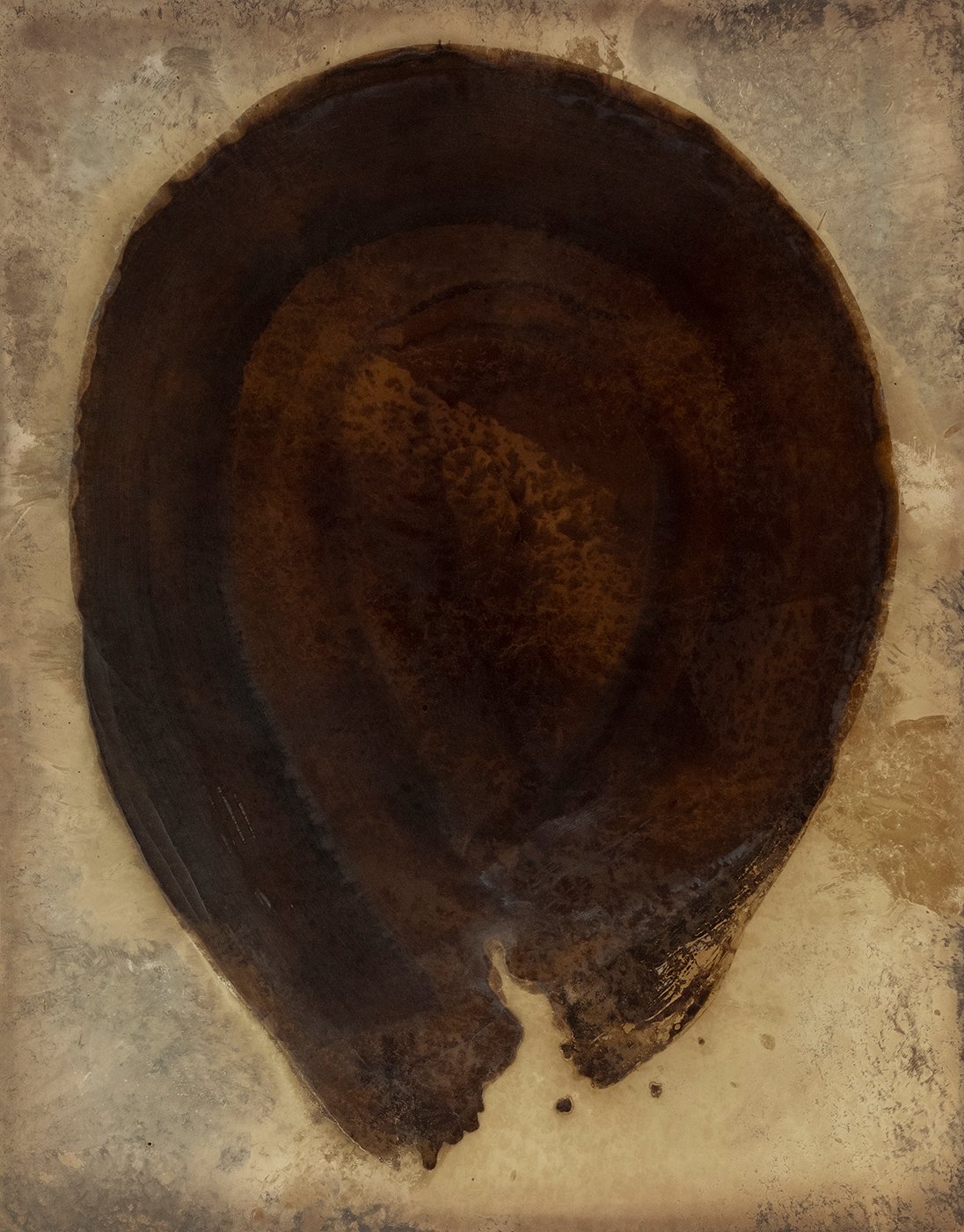

FL: Manifestation of Light and Energy is a reaction to a series of family passings in the last four years. I am at a stage in life where I am rapidly becoming an elder after most recently losing my 104-year-old grandmother, my father-in-law, and my dearest buddy, Sparky. The level of grief has been immense these last four years as I reach a relationship with my own mortality. The body of work symbolically uses silver halides (the interaction with silver and bromine/iodide halogens) to create an image upon the silver gelatin paper that is interdependent upon the relationship of the artist (me), the gestural experience of the process (the idea), and the physical transformation of the paper itself (the result).

It is for the experience of impermanence in this lifetime that I use the analogy between halides and the cycle of birth, death, and rejuvenation. Halides are fleeting, irregular, beautiful, temporary, and require illumination to outside forces (negatives, chemical agents, and light) in order to activate. Nothing is permanent or perfect. All things must pass and we are merely transient passengers onto our next journey. My belief is that a lifetime is an eternal journey towards the end of suffering. This body of work has been cathartic for me.

SW: It seems like form is as important as, or rather impossible to separate from, the content or subject matter that you’re tending to. Can you speak a bit about the language of abstraction in your practice?

FL: The language of abstraction began very unexpectedly for me as I was searching for a new way of speaking. I began over 10 years ago gathering decayed materials in my darkroom after teaching sessions. Old film with fixer drippings, class lecture materials where I taught a certain process without proper fixing or washing, discarded light sensitive paper that would sit in the trash for days. I also began to manipulate historic peel-apart Polaroid film and decaying/distressing the material. I would consider this the rudiments of where I am today.

I was introduced to photographic artists using abstraction from viewing books by Lyle Rexer’s Photography’s Antiquarian Avant-Garde and The Edge of Vision. Also, Light Paper Process by Virginia Heckert and What is a Photograph? by Carol Squiers. I have studied and followed artists like Richard Serra, Rothko, Kline, Gerhard Richter; however, photographers such as László Moholy-Nagy, Man Ray, Pierre Cordier, Liz Deschenes, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Ray Metzker, Alison Rossiter, Meaghann Riepenhoff, and countless others have profoundly influenced my work. They gave me courage to try something that was not necessarily new, but different for my language of expression. I became obsessed.

SW: Your latest project They Tried to Bury Us but They Didn’t Know We are Seeds is a direct response to an issue that is threatening our collective humanity. Can you talk about this step in your work?

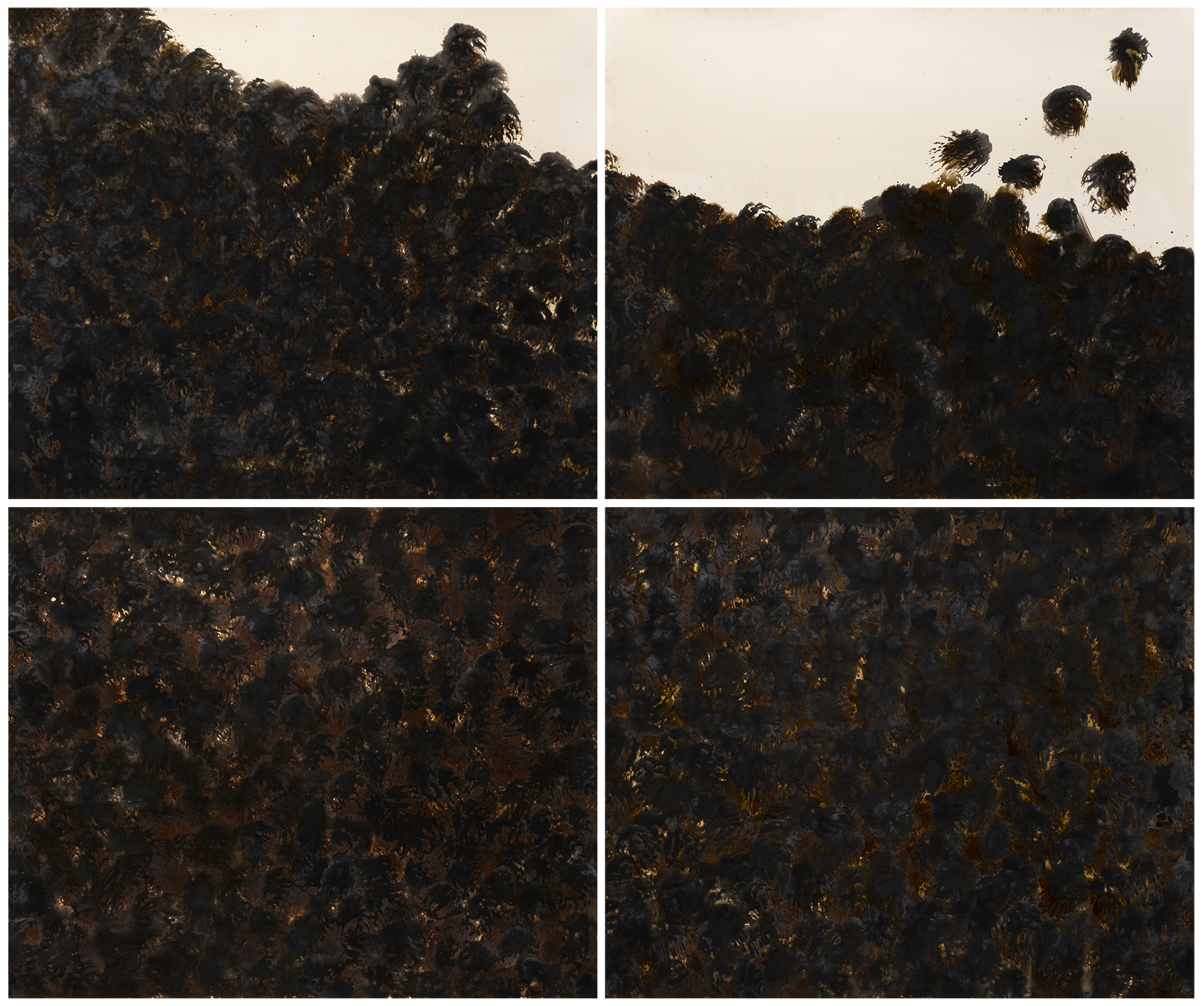

FL: Art should remain current with the times. This project is based upon the activist proverb, They Tried to Bury Us but They Didn’t Know We are Seeds. This is a direct reaction to the immoral ICE detentions, and the racism and racial profiling that has accompanied the current administration. As an Engaged Buddhist, I am tasked to stand for justice, and to help the cause of promoting compassion, equality, and ethical action. The descent of normalcy into the current day maelstrom goes against every moral fiber of our shared society, especially the rise of fascist and racist policies that are aimed at people of color and ‘illegal’ immigrants.

The very term is racist, for no human is illegal—no human should be subjugated to unrelenting fear, and children of any race, religion, or creed should be cared for without regard to immigration status. My work has been informed by the moments of hopelessness and despair, with the anticipation that there will indeed be a day of reckoning. I am engaged with donating resources to social justice organizations and remain active with my teaching practice to help the future leaders of this society.

SW: How did you come up with a visual language to deal with this subject?

FL: My approach to my last two bodies of work began in 2022 with a dream of chemical reactions, a devotion to approaching cameraless imagery with a different voice, and a need to get my emotions down on paper. Like the previous body of work, I am solely working with brushes and chemical reactions to symbolically react to actions that may occur hundreds or thousands of miles away but affects us all as moral people who stand for justice.