While Europe has historically been a common destination for refugees, the year 2015 saw a sharp surge in the arrival of migrants on European shores, a large proportion of them fleeing escalating conflicts in Syria and across the Middle East. During this time, the media played an instrumental role in shaping attitudes towards migration. Rarely did the coverage focus on the wider context of the refugees’ plight or represent them as individuals; instead, they were framed as a threat. Deeply unhappy with the way the refugee crisis was represented in the news, Italian documentary photographer Giovanna del Sarto felt compelled to do something. For her, being a photographer was simply not enough.

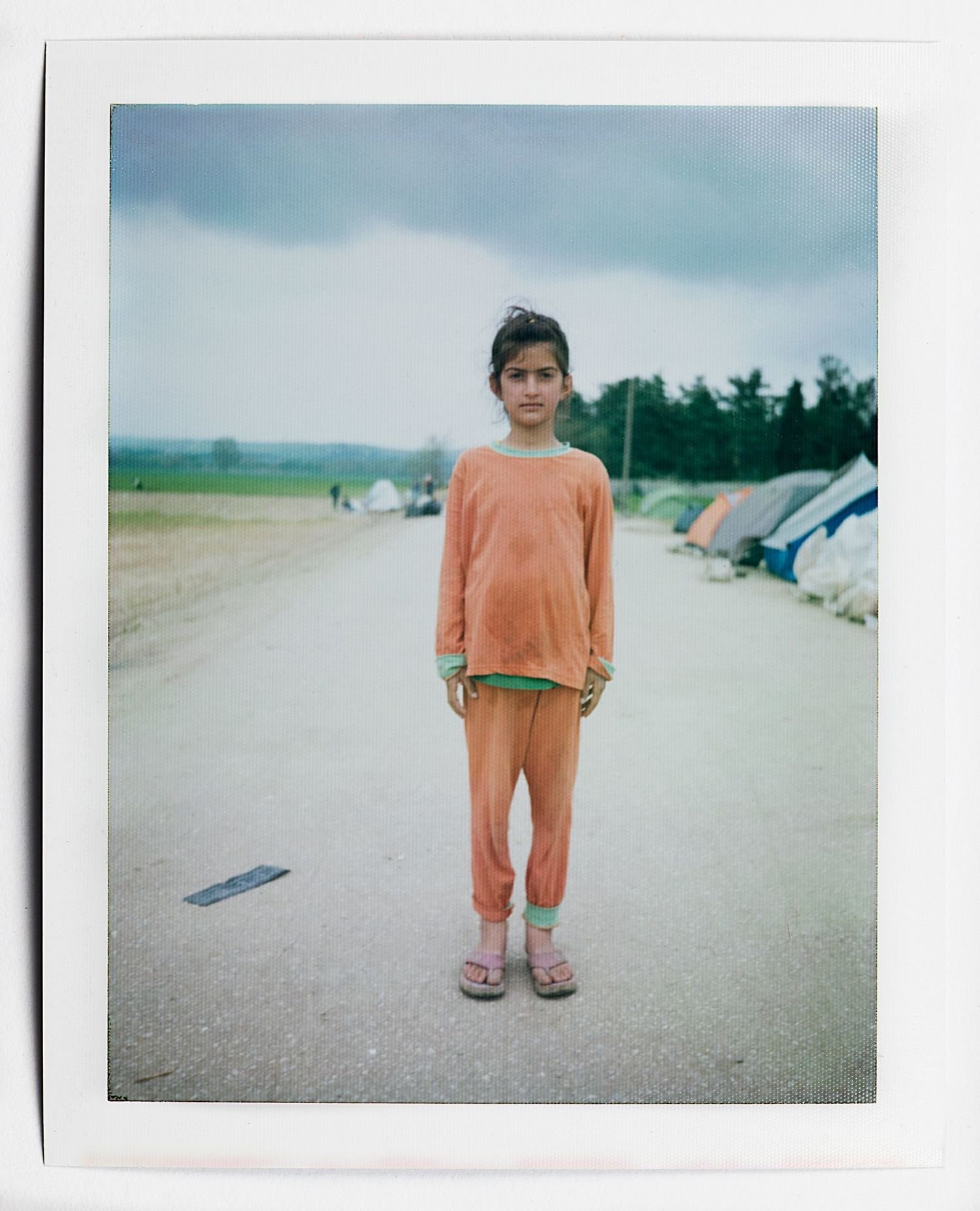

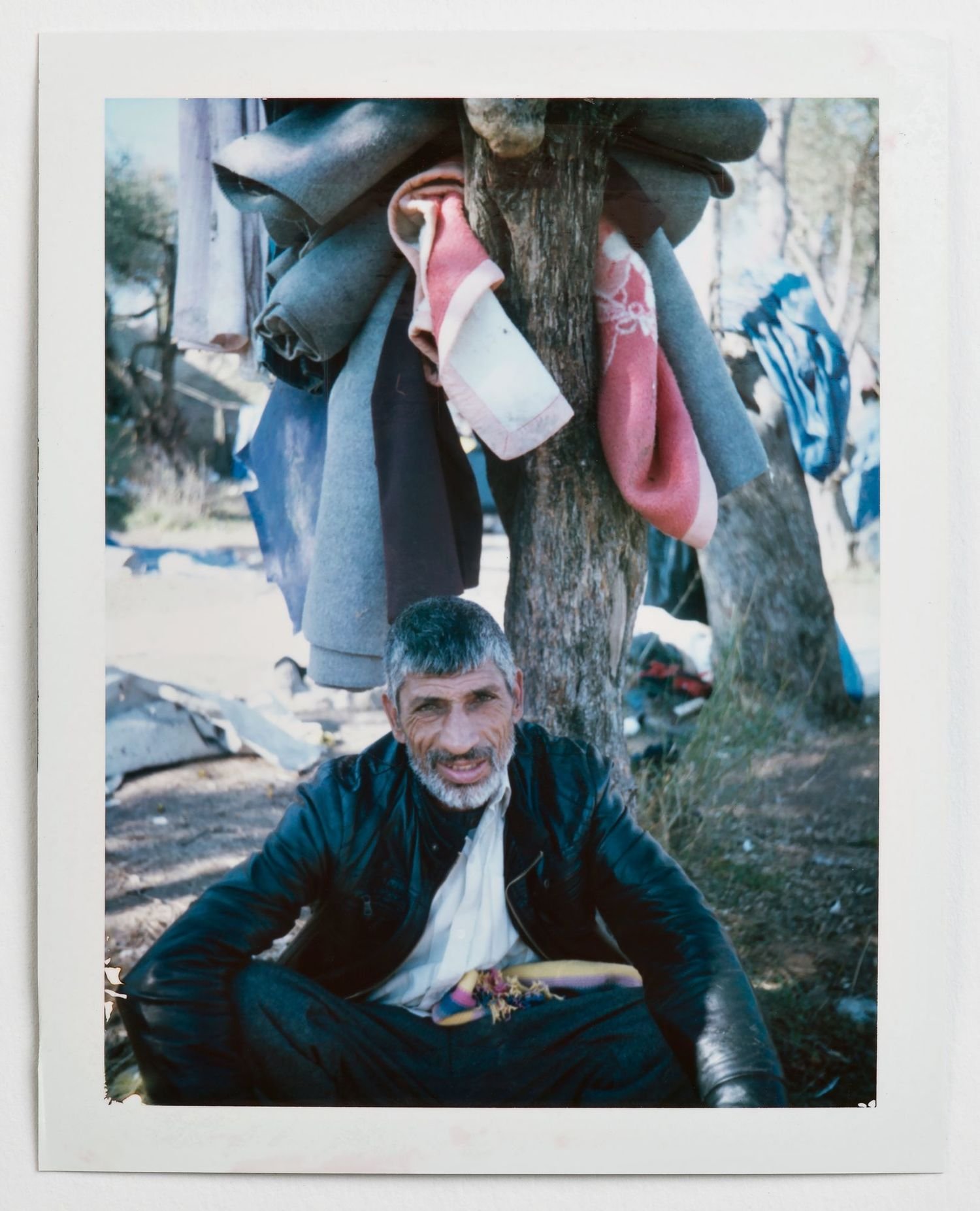

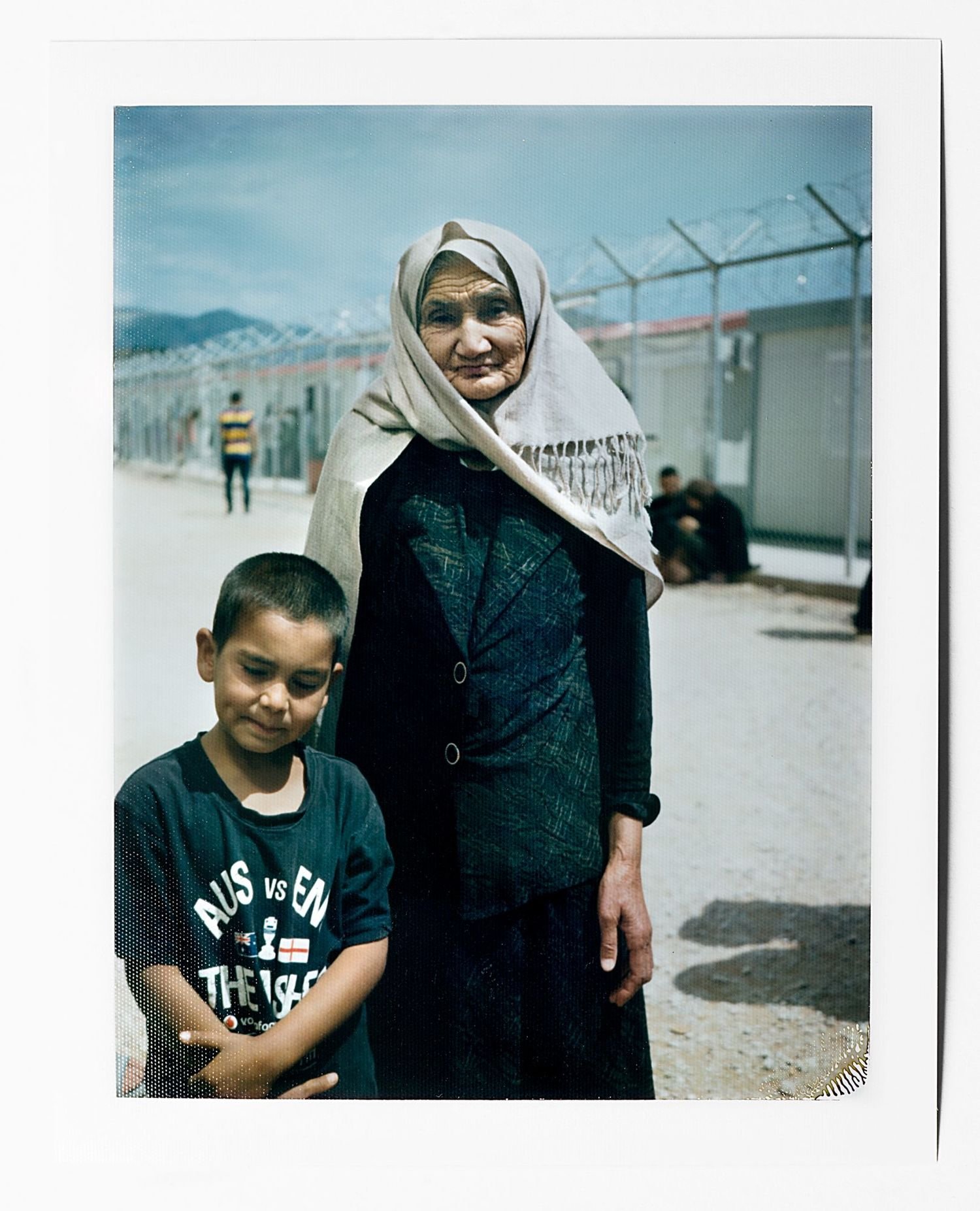

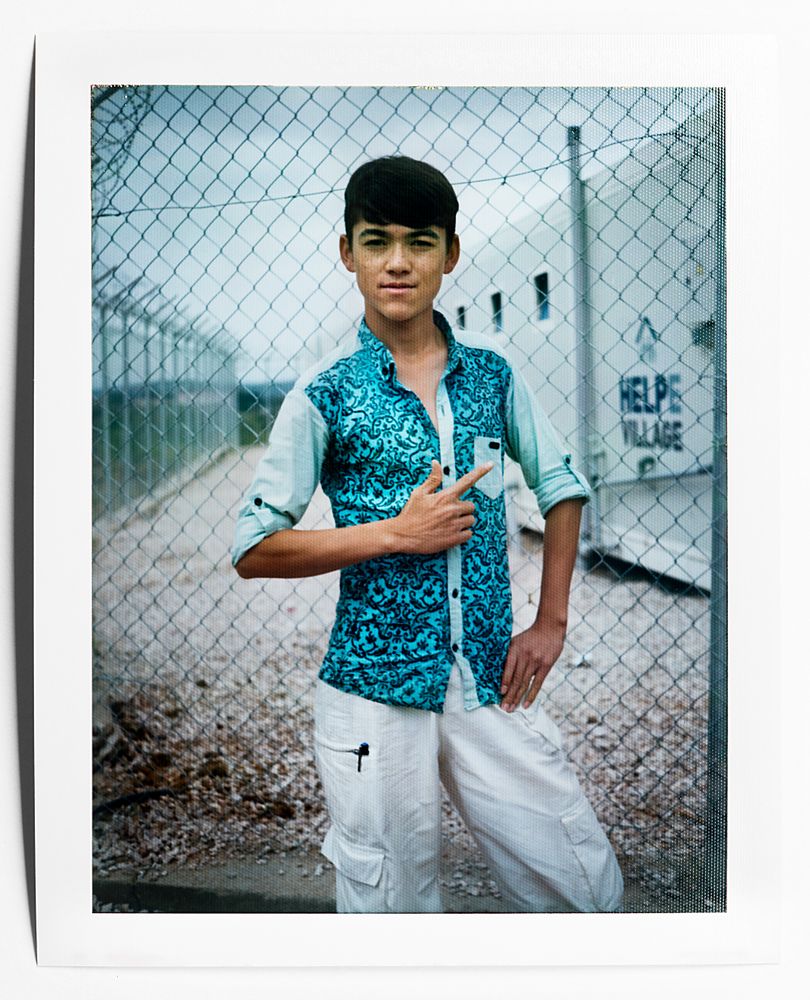

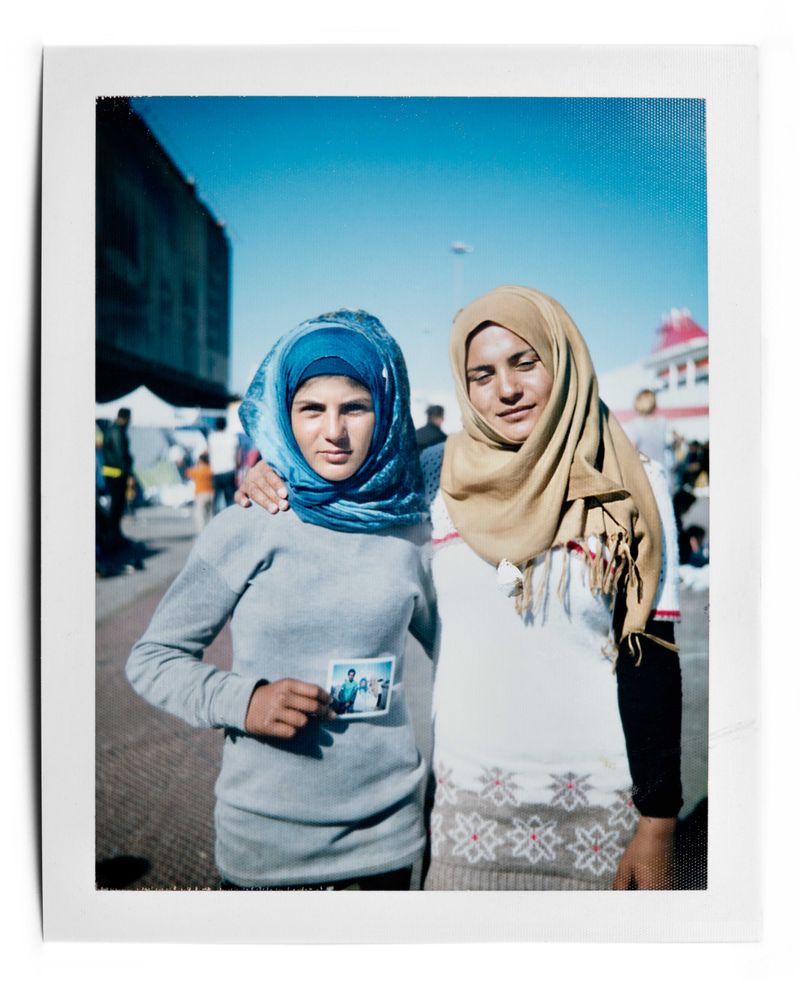

During a volunteer trip to Preševo, Serbia in 2015, she began working on her project A Polaroid for a Refugee. With her Polaroid Land camera, she captures portraits of the refugees she encounters. After the interaction, she keeps one for herself and gives the other to her subjects as a gift to carry on their journey—something to look back at in later years.

When she first arrived in Serbia in 2015, del Sarto recalls making a very clear choice. “There are so many skilled photojournalists out there taking amazing pictures with digital,” she says, “and for me, I felt that there was nothing I could add. The moment I decided to use my Polaroid camera, though, everything changed. It feels completely different than digital photography—you slow down time. You have to take a minute to ask your subject for permission, then you take the picture, and then immediately you have something to give back to them. So that became the project—it was born out of a desire to give something back.”

Del Sarto explains that this process of giving happened naturally. By offering the individuals something tangible that they could take away, they engaged more deeply with the work. But the project does not end there. To encourage a continuation of her relationship with her subjects, del Sarto asks each individual to let her know once they have reached a safe place. “This is a message of hope,” she explains, “which, sadly, for some, may never be fulfilled.”

Nevertheless, there is something in del Sarto’s engagement that seems to rub off on us, the viewers. The “family portrait” style of the images—as well as her long-running follow-up with each of these photographic subjects—invites us to see a more personal and human side to the story. We view the people in the photographs not as anonymous swarms typically shown in the media, but as individuals—reminding us that under different circumstances, the people in the images could be you or me. In approaching the situation from this unique viewpoint, del Sarto offers a refreshing perspective on the largest refugee crisis since World War ll.

“While the main ambition is to raise awareness of the situation,” says del Sarto, “I’d also like to be able to reach communities. Eventually I’d like to explore side stories, and ideally I’d like to speak again with the people who have reached out to me since I photographed them. So far, around 4-5 people have contacted me to say they’ve reached a safe destination; I’m still waiting (hoping) to hear from the others.”

—Eva Clifford

More of Eva Clifford’s writing (and photographs) can be found on her personal website or her Instagram feed.

If you’re interested in seeing more work on this and similar topics, we’d recommend the following previous features: Let Me Tell You, Sara Furlanetto’s project that recounts the personal stories of refugees through notes written directly on the photographs; Lost Family Portraits, a series that gives center stage to Syrian refugees in Lebanon who have come forward to share their stories; and Lingering Ghosts, striking portraits by Sam Ivin that chronicle the excruciatingly long wait for asylum in Britain.