What can photography speak that words cannot? In Torrance York’s Semaphore, the artist builds a visual language to express her experience of daily life following her life-changing Parkinson’s diagnosis. Across a series of poetic images, the world is described anew, seen through a different lens.

York’s images talk to one another, building a delicate rhythm that speaks both of rupture and strength. Familiar things take on new and intimate meanings as the artist’s shifting, curious perspective, shaped by her changing body and mind, transforms the way she looks at her surrounding environment and her interactions within it. With the artistic process as a teacher and photography as a tool, the photographer navigates the slow path to acceptance, building the “growth, patience and perseverance” she describes as key to moving forward.

In this interview for LensCulture, York speaks to Sophie Wright about the importance of voicing one’s own perspective, the metaphors of her visual language and the powerful health benefits of making art.

Sophie Wright: What impulses underlie and drive your artistic practice?

Torrance York: Through photography I connect with what I find or arrange in the world. The precision of the medium and the ability to manipulate how my subject is portrayed using point of view, composition, and focus, give me a sense of control. With my camera, I frame and honor my subject, eliminating distractions on the periphery. I enjoy that photographing slows me down and invites close observation.

As the subject of a 1978 photobook about my life as a child gymnast, A Very Young Gymnast by Jill Krementz, I experienced the phenomenon of being presented from one person’s point of view. Photography is powerful in its reach and privileged relationship with the concept of ‘truth.’ I felt compelled to voice my own perspective and, I suppose, my own ‘truth.’

For my MFA thesis at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), I created a video that mined the experience of being represented by the book and the media attention it received. I appeared on television on the Merv Griffin Show, the Today Show, and other programs to promote the publication in 1978. Examining issues of representation was then current in the medium through the work of artists such as Sherri Levine, Lorna Simpson, Richard Prince, and Paul Pfeiffer. I wanted to look more closely at the impact the book had had on me.

Between RISD, from which I graduated in 1994, and 2019, most of my projects focused on the landscape. Nature provided an abstract language to depict emotion through the relationship of elements in the scene. For example, I titled an early 1991 series of black and white landscapes, Refuge & Questioning.

SW: Semaphore grew out of your Parkinson’s diagnosis, 10 years ago. Can you tell me more about the origins of the project? What prompted you to pick up the camera during this life-changing moment?

TY: Semaphore grew out of an assignment in Sandi Haber Fifield’s long-term workshop, ‘Finding Your Vision.’ I told the story in the book’s acknowledgements because this spark was a gift. Essentially, Sandi requested that each of us provide two adjectives to describe ourselves. She then assigned each of us to make pictures of a different person’s adjectives. I was given ‘nurturing’ and ‘optimistic.’ While working on this task, I realized these were characteristics I wanted to further develop in myself—to help me manage my diagnosis.

I felt as though a spigot had been opened. Everywhere I looked, I found metaphors to express feelings or ideas I did not realize I had been contemplating. I chose the epigraph from Art & Fear: Observations On the Perils (and Rewards) of Artmaking (1994) by David Bayles and Ted Orland, because it described my process with Semaphore, “…notice the objects you notice… Or put another way: make objects that talk—and then listen to them.” After capturing images and looking at them, ‘listening’ to and interpreting them, I would plan next steps to refine the expression or find new subjects. Around this time, I began working with a psychologist who had training in art therapy, and the images enriched our discussions.

SW: You’ve spoken of photography as a companion of sorts as your perspective shifted due to the effects of your illness. How did the role of photography in your life evolve alongside the changes you were going through? And vice-versa, how did the physical experience of Parkinson’s reshape your approach to your practice?

TY: There is no cure for Parkinson’s disease. Medication can address the symptoms, and exercise has been proven to slow the disease’s progression. I endured a spectrum of symptoms in varying degrees during those first seven years, which the medication I began in 2022 helped reduce. I still feared developing other symptoms I had learned of or observed in others. Some of the many changes I recognized could also be due to aging. I feel driven to decipher the protean line between these simultaneous forces of change, aging and illness. Yet, like the goal of ‘acceptance,’ the boundary line is a moving target over time.

In terms of the physical changes affecting my photography, to compensate for my relative unsteadiness due to Parkinson’s, I now shoot at higher shutter speeds and use a tripod more often. I do not want to compromise on sharpness. And, of course, my physical changes served as content for much of the series.

The Semaphore project is a silver lining to my illness. My proclivity to articulate and understand the value of my photography practice dovetailed with my need to unpack the many dimensions of Parkinson’s and what they mean for me. No nuance was too small. If something I saw triggered a connection to a change in my world or worldview, I photographed it. Later, I could select the most impactful images while editing my work.

SW: Across its pages, Semaphore invents a stimulating and enigmatic visual language that grapples with the difficulties of articulating the experience of illness. Can you tell me about the dialogue between the precise scientific visuals and the stuff of daily life—the poetic patterns of natural landscapes, intimate encounters and domestic moments—and how you arrived at that approach?

TY: It is almost impossible to forget that I have a movement disorder because I am inherently moving when I am awake, and those movements often feel different than they had felt previously. This awareness is ever-present. This is my now. The types of subjects I photographed in Semaphore include the body, nature, light, and moments from daily life, which I combined with medical images and text phrases. These themes captured my attention. I kept my camera close by.

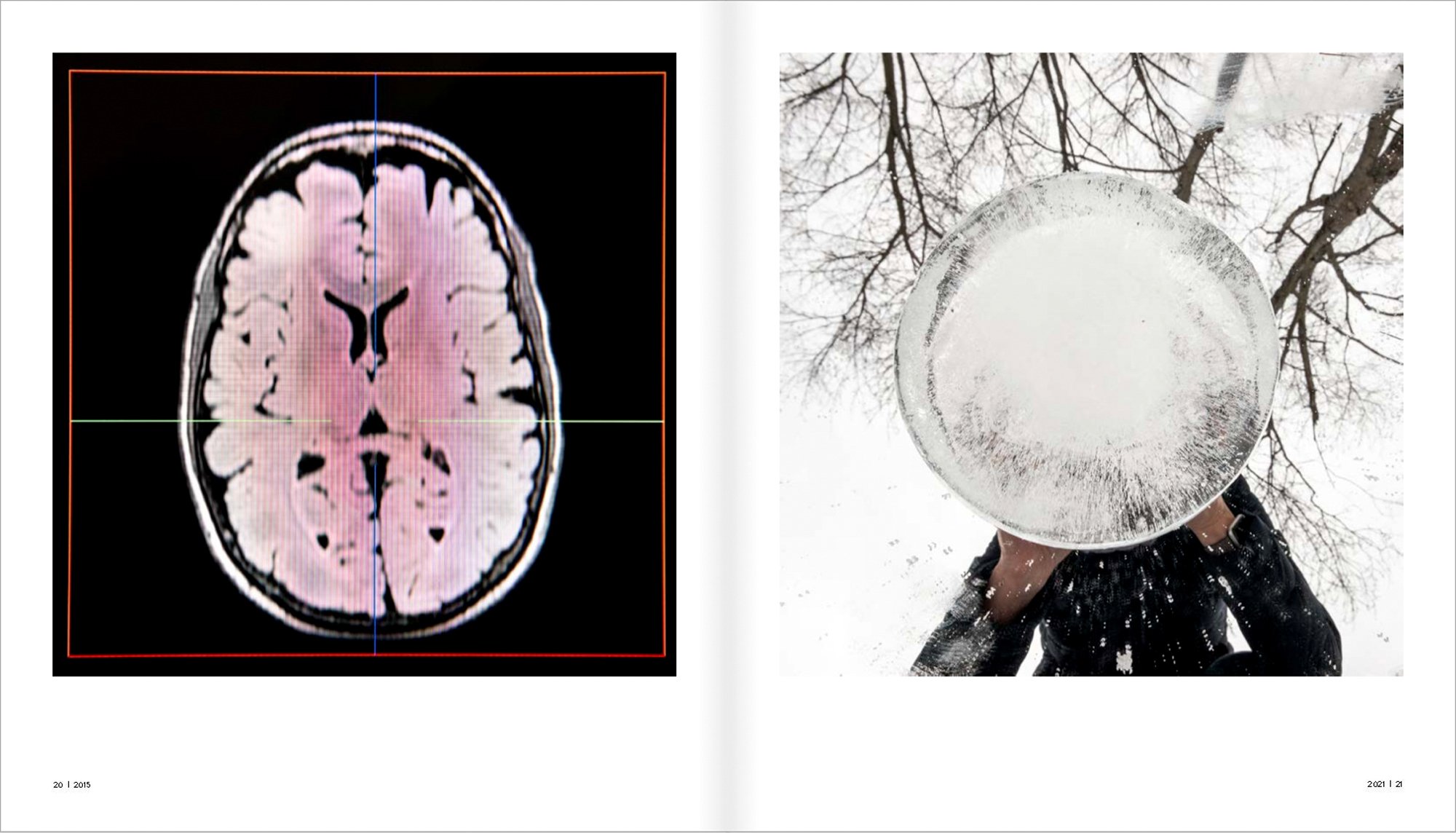

When setting up shots to illustrate ideas, I often chose toys I had enjoyed in my youth—such as tangrams, construction blocks, and Cuisenaire rods, because they had given me a sense of mastery back then. The medical images are all of my body. They track history, provide evidence of when I was injured or ill, and they point to concern for how my body was or was not functioning at that time. I am fascinated by the human body and its skeleton. Using the X-ray and MRI images, I drew connections among forms inside and outside the body, and between the psychology of the mind and the anatomy. I present some of these comparisons over two-page spreads in the book.

I hope the sequencing and accumulation of images build meaning and enable the reader to grasp aspects of my experience at this life-changing inflection. To weave the various themes and non-chronological sources into a representation of my personal journey, I use repetition of the types of images and recurring geometric forms as threads throughout the book.

SW: How does this language speak to the specifics of living with Parkinson’s?

TY: In Semaphore, I picture my goals and aspirations as well as my new challenges and fears. My research on brain health and wellness helped inform these goals. Understanding the connection between stress and Parkinson’s, for example, I realized I had to find more ways to decompress. To picture this goal, I created an image of my arm on top of the bubbles in a bubble bath. Or, knowing that I must be patient and adaptive to face my new frustrations and reduced capabilities, I took special note in nature of the way trees or vines adapted their growth around a fence, and I photographed that.

Some of the images that focus on light are included because I found them inspiring, but also because I want to be inspired to focus on the light and to choose the optimistic perspective. With the knowledge that engaging in new activities can build new neural pathways (neuroplasticity), I photographed a sprouting bean and nascent ferns to demonstrate the growth of something new.

Several images point to the importance of human connection and love. The hug, holding hands, and skin on skin. On the side of challenges and fears, I pictured tools or tasks that had become more difficult, for example, a knife, a whisk, or buttoning my shirt cuff. My walking gait is no longer symmetrical. The asymmetrical composition of tangrams speaks to that. Other images address concepts such as anxiety, brain fog, and difficulty with balance and posture. One image that I find hard to look at is the one of the wasp’s nest. Part of the structure is carved out such that it looks like a mouth. Another spot looks like an eye. Seeing it as a face, it appears monstrous to me. My uncertainty about my health and well-being at the time felt equally horrifying.

SW: The idea of acceptance seems to be being worked out through the images, and though they do not shy away from the pain and confusion of illness, the feeling tone of the book has a gentleness and grace to it. Can you tell me about what the process of working on and making Semaphore did for you personally? And what about the act of sharing?

TY: You might think that presenting work on a subject this personal would be disarming; however, I have grown stronger and felt more fortified through the process of creating AND sharing the work.

The book or exhibit serves as a tool for dialogue, different with each individual or audience. I have had the opportunity to present Semaphore at Grand Rounds for the Neurology departments of three US medical schools, and at the World Parkinson’s Congress in 2023. The series has been exhibited at Rick Wester Fine Art, Chelsea, NYC, the Danforth Art Museum, Framingham, MA, the United National Albano building, NYC, and St. Lawrence University, Canton, NY, where I met with several groups of students. Semaphore has created a platform from which I can advocate for the work, for Parkinson’s, and for the power of art.

It is an exciting time for research in neuroaesthetics—an emerging discipline within cognitive neuroscience that is concerned with understanding the biological bases and benefits of aesthetic experiences. The neurochemical dopamine is critical in aesthetic and creative experiences. In the brains of people with Parkinson’s, the dopamine-making cells are dying off. There have been studies looking at the extent to which the arts and creativity can be specifically therapeutic for people with Parkinson’s. A new study is set to take place soon in The Netherlands, led by pioneering neurologist and advocate for holistic Parkinson’s care, Bastiaan Bloem, MD, PhD.

My initial ambition for Semaphore, to foster a greater understanding of living with Parkinson’s and encourage dialogue that includes the often-taboo subjects of illness and vulnerability, has expanded. From this new perspective, I advocate for the arts as a force to benefit the health of our bodies, brains, and spirits. While Semaphore is relevant to the Parkinson’s community, it also connects with others whose journeys require growth, patience, and perseverance to move forward.

Now, after ten years of living with PD, I must find resilience in the face of new obstacles presented by the confluent forces of aging and illness. With my current series, Interstices, I navigate the challenge of looking into the space between now and the time when I will be less capable. I peer below the surface at the non-motor and psychological symptoms—symptoms which are less visible but feel no less daunting.